LSE alumnus Connor Vasey looks at how democracy has evolved in African countries.

A lot of anticipation surrounded the release of Dr Nic Cheeseman’s latest book Democracy in Africa, evident by the buzz among the crowd at his book launch at the Royal African Society on 12 October 2015.

Cheeseman ran through the core objectives of the text: (1) Pay homage to the legacy of democracy in Africa; (2) fully contextualise African democracy from a broader historical perspective; (3) provide a framework through which to properly understand the rationale underlying the decision-making processes of African leaders. Beyond the resources it provides, the book also advances a number of key conclusions, including an emphasis on the value of presidential term limits, noting the startling fact that if an incumbent party is able to have the same leader run twice, they will win 85% of the time compared to 50% when this is not the case!

Although the panel discussion delved into a number of interesting topics, this article only seeks to explore the underlying, and only partially-referenced, theme of the event: the ‘Africanisation of democracy’.

To begin it is important for us to decide whether this is a discussion worth having. Indeed, does it make sense to talk about democracy being ‘Africanised’? Is there something about ‘true’ democracy which is intrinsically ‘non-African’? The short answer is no. As Cheeseman highlights in both his book and monologue, aspects of democracy in Africa have in many historical cases proven more advanced than European contemporaries. Today almost all surveys on the continent indicate that a majority of Africans want and value the right to vote.

Moreover, many aspects of modern-day political systems in Africa which we might deem undemocratic are simply caricatures of what one can find elsewhere in the world. For example, as Stephen Chan states, an excessively strong president bears the hallmarks of post-Napoleonic France and the hopeless participation of opposition parties in the Zimbabwean parliament is mirrored in states such as China or Singapore. What we see, then, is that in some respects Africa’s democratic journey is typical.

However, what I want to illustrate is where Africa has diverged from the well-trodden path. There is no doubt that cross-country comparisons will tell different stories and that no two states are equivalent. That said, what I want to ask is: are there certain trends, speaking about the continent in the broadest terms, which are quintessentially African? Here I highlight two candidates:

(1) The balancing act of tradition and democracy

Modern-day Africa is a melting pot of ‘old meets new’ and, as such, infiltrating the rhetoric of many campaigning officials is an old sectarian- rather than issues-focused campaign. While matters of education, health and the economy fizz with expectation, the word of traditional leaders and divisions along ethnic, religious or regional lines never cease to impassion the electorate.

Carolyn Logan has found that in sub-Saharan Africa public sentiment towards traditional leaders is typically more positive than towards their parliamentary representatives. Although cross-country analysis reveals variations (e.g. this point is less applicable to South Africa than Kenya), the trend is positive. The challenge for governments is to balance the unifying power of traditional voices, albeit patriarchal voices, with the advancement of democratic institutions.

This balance is not easy to strike: Botswana has been under fire for the flogging of Zimbabwean nationals despite corporal punishment being a core pillar of the quasi-traditional sentencing structures. In January we witnessed a great regional divide as Zambians took to the polls with the West and East voting disproportionately for the United Party for National Development and Patriotic Front respectively. As Buhari heralded in a new age of peaceful power transfers in Nigeria, the mud-slinging between Northern Muslims and Southern Christians continued. Even in South Africa, often the model of a successful African economy, race continues to be a key buzzword among the electorate (there have been recent calls to remove the Afrikaans verse of the national anthem).

(2) Pan-Africanism

The African identity is a unique one. Although most Africans are proud of their national heritage, there is a particular pride for being part of the wider continent which has eluded the European project and other regions of the world. For many, with common identity comes a common goal: the advancement of Africa. This manifests politically and economically with bodies such as the African Union, ECOWAS, EAC, SADC, etc. as well the rekindling of discussions regarding the Tripartite Free Trade Area.

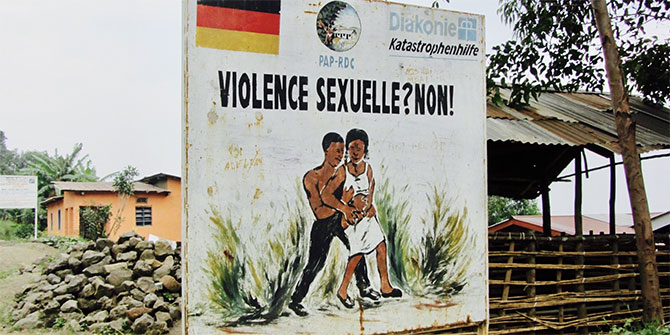

Even more interesting, though, is the international actions of national bodies. For example, both Y’en amarre of Senegal and Balai Citoyen of Burkina Faso (both lobbying groups in their home countries) converged in the Democratic Republic of Congo earlier this year in order to establish dialogue as President Joseph Kabila looks more and more likely to stay put beyond his term. Collaboratively the two groups have set up conferences, youth forums and grass-roots lobbying groups in the DRC to peacefully oppose a possible bid by Kabila to hang on to power.

The AU’s own Pan-African Youth Union (PYU) has tasked itself with inspiring political engagement and activity across all member states. It looks to galvanise activity among the young population in particular to participate more actively and responsibly in the politics of their countries.

Social media has provided an exceptional source of international commentary between citizens of African states as they engage one another on a Pan-African level regarding issues which do not directly affect them. We see this also in increased efforts among the young to learn common languages such as English, French and Portuguese so as to facilitate dialogue with regional neighbours.

Here I have barely scratched the surface of Africa’s contemporary democratic story. While the Economist’s Democracy Index identifies Mauritius as the only ‘true’ democracy in Africa, one might question what exactly democracy is to look like in an African context. Above are two reasons why we may never see a copy-paste European democracy in Africa (‘true’ democracy), but two reasons why we ought to be excited by Africa’s own take on that.

This post is based on the launch of the book Democracy in Africa and discussion hosted by the Royal Africa Society (RAS) at SOAS. Follow this link for a podcast of the event.

Follow this link to read the Africa at LSE book review of Democracy in Africa: Successes, Failures and the Struggle for Political Reform by Nic Cheeseman.

Connor Vasey is a LSE alumnus and former Head of Media for the LSE Africa Summit.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.