How would the UK fare outside the European Union? In theory, UK could stay in the common market even upon leaving the broader EU. The EU could offer UK satellite status, that is, free access to the common market if it continues to pay up. However, the terms of the divorce would be negotiated between EU that represents 83% of joint GDP and UK with 17%. Holger Schmieding explains.

How would the UK fare outside the EU?

Nobody knows for sure. A divorce can be smooth, causing only modest damage. Or it can be messy, inflicting serious pain on everybody except the lawyers. It would all depend on the policy choices taken by both sides following a vote for Brexit on June 23, 2016.

But history offers a stark lesson

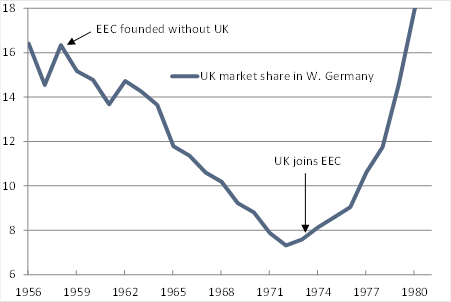

From 1958 to 1972, the UK stayed outside the European Economic Community (EEC). As the EEC members traded more with each other, the UK lost market share fast. The ratio of German imports from the UK relative to its imports from fellow EEC members fell by more than half. Trade diversion hurt the UK so badly that it began to ask to be let into the EEC five years after staying aloof in 1958.

Europe made the difference

After rejecting two UK applications to join in 1963 and 1967, the EEC finally opened its door to the UK in 1973. As a result, the UK’s share of the German import market rebounded strongly (see chart). Beyond the dismantling of trade barriers, a decline in the real effective exchange rate of sterling after 1971, UK austerity under the 1976 IMF program, and rising UK exports of North Sea oil also helped that trend.

It is the common market

Our chart is about the common market. In theory, the UK could stay in that market even upon leaving the broader EU.

But that comes with three snags:

1. The bedrock of the common market is a set of common rules and regulations. They are imperfect. But they are the rules.

2. Free trade in goods and services is tied to the free movement of capital and labor.

3. Members must pay into the EU budget.

The EU could offer the UK satellite status

Free access to the common market would continue, if the UK continues to pay up, abides by all Brussels rules and regulations, lets the European Central Bank supervise the London market in euro products and treats any Polish plumber like a native worker. But whether the EU, whose top priority would be to avoid setting a precedent that could encourage other would-be leavers, would indeed offer such a sweet deal to a country that has just spurned it, is highly questionable. And that the UK, having just rejected the EU, would really accept a satellite status that would be worse than its current position, looks unlikely. The terms of divorce would be negotiated between an EU that represents 83% of joint GDP and a UK accounting for 17%.

Trade will continue

Have a guess who would dictate most of the terms. That would leave a tough choice for the UK between accepting whatever Europe offers and going for a long and contested divorce battle. Of course, the UK would still trade with the EU even after a messy divorce. But its access would be restricted in those fields in which it does not fully abide by all EU regulations. The UK would be at a disadvantage, as it had been when it had remained outside the EEC 1958-1972. We know how that ended for the UK.

The UK did not even have a free trade agreement with Europe before accession, and tariffs were far higher than they are now even assuming the EU won’t give us a free trade deal (which would be a classic example of cutting off their noses to spite their faces). It is not certain that they will give us a deal, but it is highly likely. Germany does not want a trade war with us, or we will stop buying their BMWs. But even so, do we want to stay in an organisation that is prepared to blackmail us and use threats to stop us leaving? If the EU really is willing to cut off it’s nose to spite its face, simply to act as a deterrent, does this not show that this is an organisation which puts self-preservation above the best interests of its members?

And a word on “non-tariff barriers”. When politicians want to eliminate these, they want to eliminate democracy. Small workshops selling products to local markets do not need the same regulations as Polish factories, but the “elimination of non-tariff barriers” means that they do. Of course, when a business trades with another country, it needs to ensure that those products meet the standards of that country. But this does not mean that it needs to meet those standards all the time, and businesses who don’t export don’t need to either. Perhaps the business that exports will feel that it is more efficient to meet the higher standards all the time, but that does not require political integration. The elimination of non-tariff barriers simply means centralisation and the erosion of democracy.