Brexit is a process, not an event. As Tim Oliver sets out, that process involves 13 different negotiations and debates between multiple decision makers and other political actors. Each negotiation overlaps and shapes the others. While they need not add up to make Brexit a crisis, finding a way through will be a significant challenge for all involved.

Brexit is a process, not an event. As Tim Oliver sets out, that process involves 13 different negotiations and debates between multiple decision makers and other political actors. Each negotiation overlaps and shapes the others. While they need not add up to make Brexit a crisis, finding a way through will be a significant challenge for all involved.

Theresa May’s promise that ‘Brexit means Brexit’ sounds, as the Washington Post’s Sebastian Mallaby pointed out, a bit like telling a toddler that ‘bedtime means bedtime’. There will be a bedtime. But as every parent, aunt, uncle, godparent or babysitter experiences at some point it’s never clear when, where and how bedtime will happen.

As has become apparent since the 23 June vote, Brexit is not going to be a process that is easy to define, implement and put to bed. Brexit is a series of interconnected negotiations, debates and votes that is, for some, potentially open-ended. This is not to overcomplicate Brexit. If anything, by breaking it down into its component parts we can clarify our understanding of it and better appreciate who the various players will be, what fields they will play on and therefore who will enable or constrain Brexit.

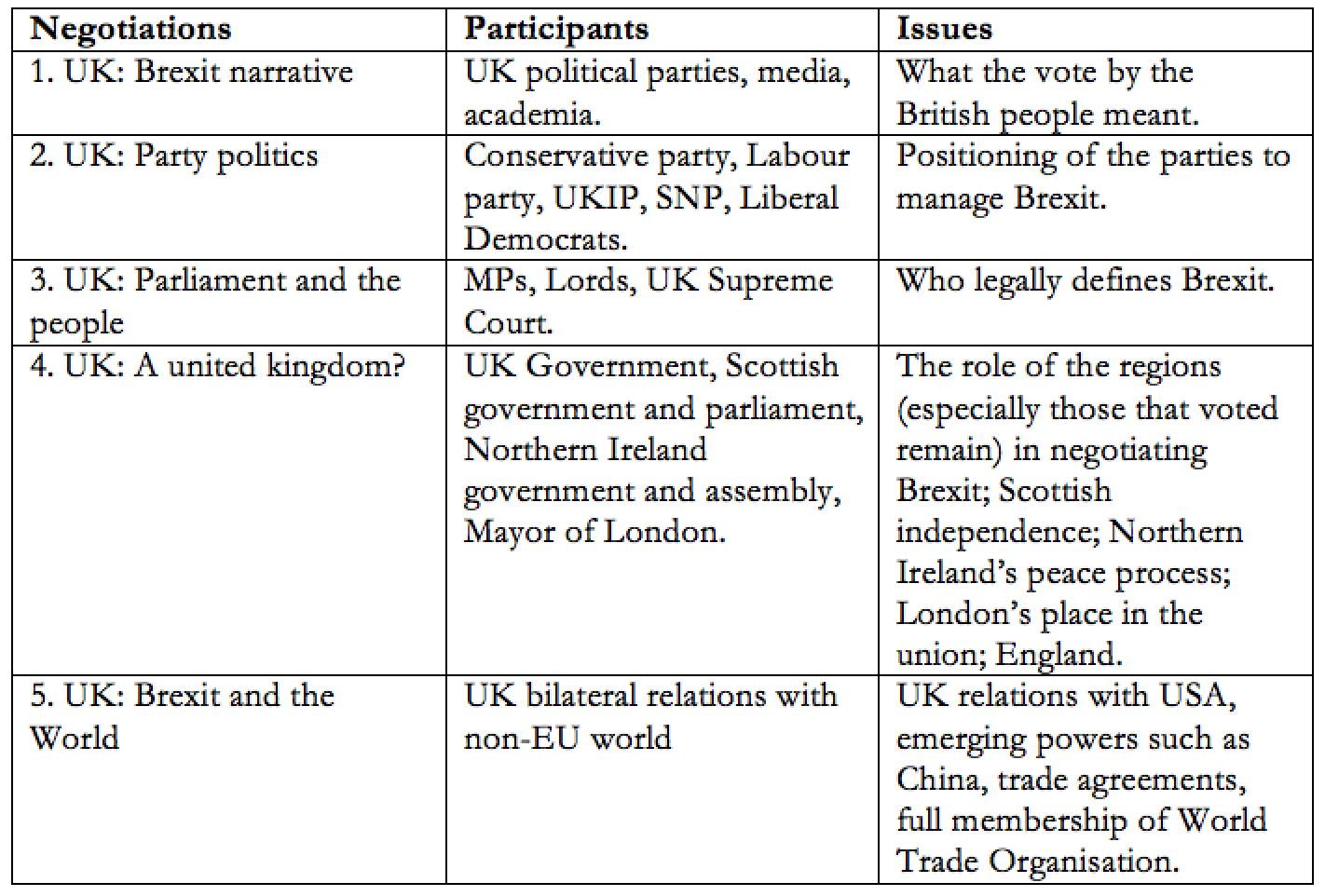

What we are now witnessing are thirteen negotiations and debates that can be divided into three groups, all of which are summarised in the tables below. The first group of negotiations are taking place within the UK and revolve largely around defining what the British people’s vote to leave sanctioned in terms of a Brexit policy to be pursued by HM Government.

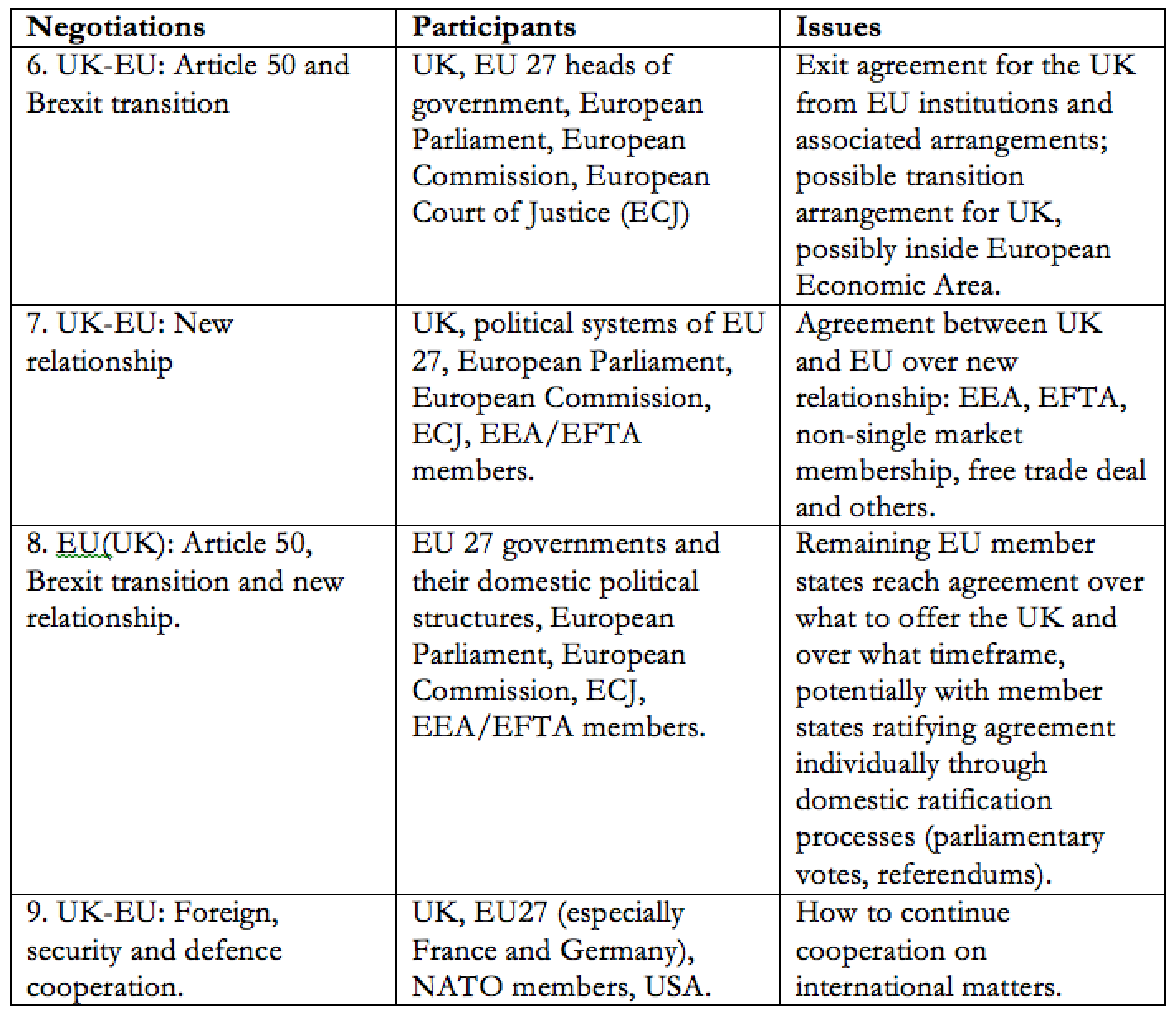

The second set of negotiations is between the UK and the EU and cover not only an exit agreement, but a new post-withdrawal relationship, a possible deal for a transition between the two, and the need to find ways forward in areas of mutual interest such as foreign, security and defence matters.

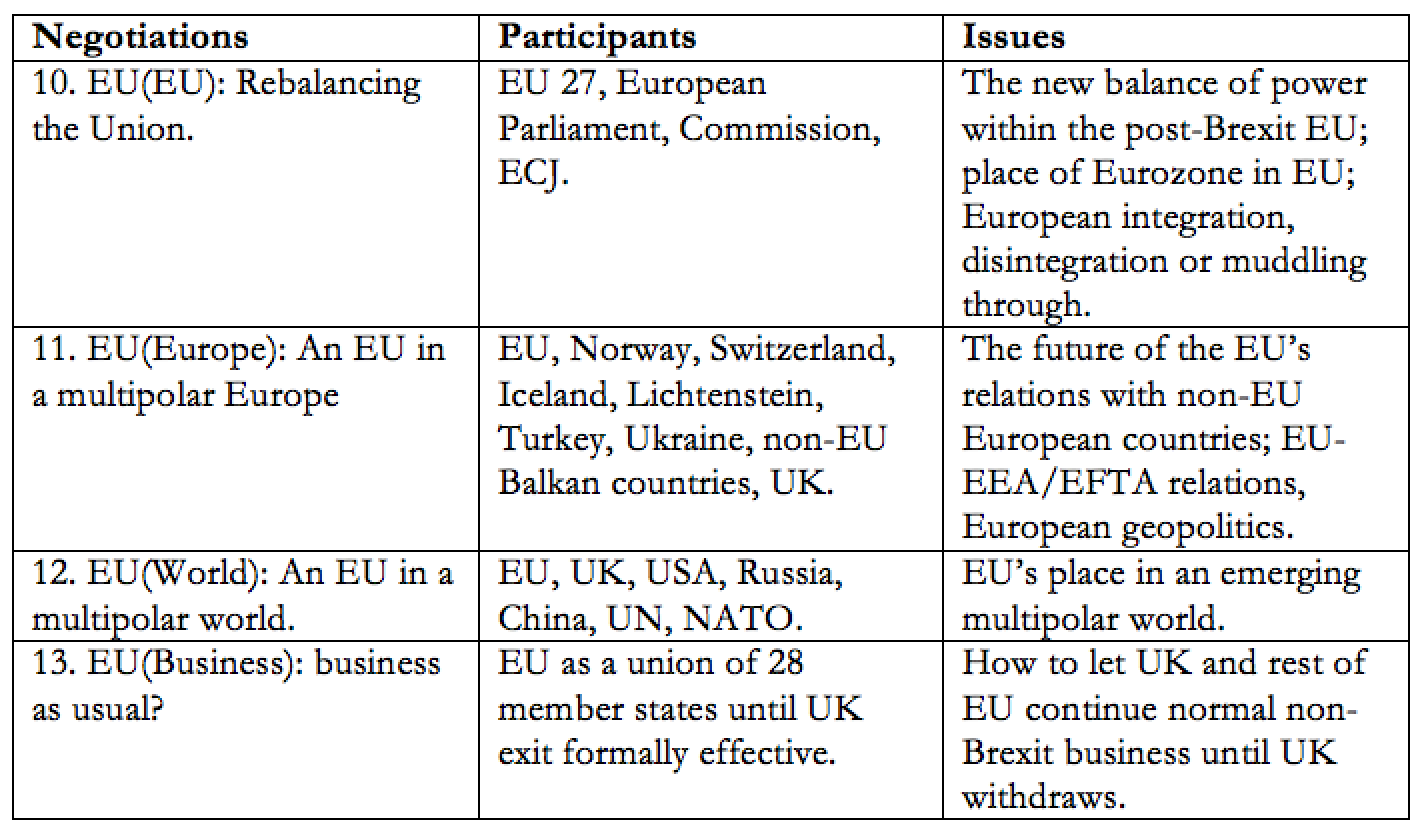

The final group of negotiations will be amongst the remaining EU, a development that until recently was with only a few exceptions almost entirely overlooked in debates about Brexit in both the UK and the rest of the EU. As the Bratislava summit demonstrated, the EU not only has to reach agreement amongst itself over what to offer the departing UK. It also has to manage a changed balance of power within a Union wrestling with a series of other challenges such as those facing the Eurozone and the EU’s place in Europe and the wider world.

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom – European Union:

European Union:

The multiple players and playing fields of Brexit and the numerous ways in which Brexit could be enabled or constrained has led some to conclude that Brexit won’t happen or that it constitutes such a crisis for the UK, the EU or both that it would be dangerous for either side to push forward with it. It is possible to imagine a ‘harsh Brexit’ which sees a breakdown in trust between the various actors leading to a deterioration in relations between some or all involved, ending in significant damage (potentially a break-up) of the UK, the EU or both. That said, even a harsh Brexit could amount to a crisis that forces all involved to realise what they have to lose. The outcome could be what can be termed a ‘harsh-positive’ Brexit in which instead of muddling through Brexit – coping with it rather than solving the problems it presents – the EU and the UK find a viable solution that settles the matter.

Is Brexit a crisis?

Is Brexit, therefore, a crisis for the UK and/or the EU? Politics is the daily management of crises, and in some ways Brexit takes the long-running problems of UK-EU relations to a new level. In doing so Brexit can be said to meet the definition of a crisis as something that is dramatic, vivid, emotionally charged and carrying significant consequences. Crises are, as Rosenthal et al. argued, moments or periods of truth which test leaders and the robustness of political institutions, and in which frailties are revealed, in no small part because the limited time available limits the opportunities for adaptation. Crises capture the attention of leaders, commentators, and analysts, and so risk neglecting other big but less exciting problems.

Brexit is testing the robustness of both the UK and the EU as political unions, and threatens some of the goals either side have set whether it be ‘ever closer union’ or the idea of Britain as a great power. The time available is limited by the domestic, political, legal and economic demands facing both sides, not least the UK. Extending the time available will lessen any sense of crisis, albeit at the risk of triggering a backlash from those who would like to see the process happen quicker whatever the cost. All sides are in the early stages of feeling their way forward with an unprecedented problem. The potential for unexpected surprises remains high; not least that one actor somewhere along the way in one of the above negotiations – for example, a vote in a parliament or a legal challenge – could disrupt the entire process.

Note: This post summarises evidence submitted by Dr Oliver to the House of Commons Foreign Affairs his article ‘The world after Brexit: From British referendum to global adventure’, forthcoming in the journal International Politics, and it represents the views of the authors and not those of LSE Brexit, nor the LSE. Image credit: CC BY-SA 3.0 NY

Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Fellow of Europe-North America Relations at LSE IDEAS.

This is one of the key posts on this blog, and should be COMPULSORY READING for all those involved, or interested in, the Brexit process. It takes a level-headed approach to a process which is too often cloaked in partisan rhetoric.

There are three interlocking processes taking place within the overarching Brexit process. The UK needs to sort out where it is going (INTERNAL dialogue); the EU and UK need to negotiate their new relationship (EXTERNAL dialogue); and the EU 27 need to sort out where they are going (INTERNAL dialogue).