European leaders, including Theresa May, should take Donald Trump’s blatant opportunism at face value. The self-professed “dealmaker” appears intent on striking new international partnerships and stoking latent animosities in an effort to shake up the international order. His aim: stacking the cards more “fairly” for the United States. Paul Angelo argues that if Europe is to figure prominently in Mr Trump’s calculations, Brussels and London will have to make the Republican administration an offer it can’t refuse—one that entails greater commitments to collective security and a resounding defence of the international liberal order.

European leaders, including Theresa May, should take Donald Trump’s blatant opportunism at face value. The self-professed “dealmaker” appears intent on striking new international partnerships and stoking latent animosities in an effort to shake up the international order. His aim: stacking the cards more “fairly” for the United States. Paul Angelo argues that if Europe is to figure prominently in Mr Trump’s calculations, Brussels and London will have to make the Republican administration an offer it can’t refuse—one that entails greater commitments to collective security and a resounding defence of the international liberal order.

Earlier this week, Trump made clear in an interview with prominent European media outlets that some of the mechanisms and institutions underpinning the current global order may face the chopping block. He suggested that sanctions against Russia for the unlawful annexation of Crimea in 2014 might be eased. Meanwhile, he downplayed the importance of the U.S. relationship with Germany, refusing to answer a direct question about whether he trusts Russian President Vladimir Putin more than German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Merkel, who is credited with holding the EU together against steep odds, is up for re-election in a tight race that many see as a referendum on European integration.

Most worryingly, President Trump railed against NATO, one of the crowning diplomatic achievements of U.S. foreign policy in the 20th century, as “obsolete” and “very unfair to the United States.” In the wake of allegations that Russia influenced the results of the 2016 presidential election, the controversial remarks about renegotiating the world’s most formidable politico-military alliance have distressed leaders from Ottawa to Warsaw. Although Trump’s own cabinet picks for security posts take issue with his comments, his rhetoric leaves little doubt that Trump’s foreign policy ambitions give primacy to a special relationship with Russia.

A U.S.-Russian partnership could plausibly prove a counterweight to an ascendant China, whose aspirations in the Pacific will continue to generate regional friction and challenge U.S. hegemony, and an opportunity to stabilise the Middle East, where Russia has earned a good deal of leverage with leaders such as Syria’s Assad and Turkey’s Erdogan.

For Putin, Trump’s willingness to strike a deal is an exciting prospect

For Putin, Trump’s willingness to strike a deal is an exciting prospect. Putin credits NATO with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and sees NATO accession talks with the Balkan states, Ukraine, and Georgia as provocations against his homeland. A distracted or even dissolved NATO would certainly play to Putin’s expansionist ambitions, which have recently provoked heightened defensive postures from the alliance in Poland and the Baltic states. Trump’s rhetorical indifference to NATO and Europe, taken with his increasing cosiness to Russia, may very well signal the beginning of the end of the global liberal order—one founded following World War II and rooted in ideals such as democratic governance, free markets, economic and security integration, and a multilateral effort to hedge imperialism.

Europe, afflicted by growing nationalism and economic frustration, should not retreat in the face of such challenges, for in the absence of U.S. leadership it is up to Europe to sustain the institutions that have afforded the West unprecedented peace, stability, and economic growth for four generations. German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen rightly asserted this week at the World Economic Forum that, confronted by a possible U.S. disengagement from NATO, Europe has a responsibility to “step forward…to fight for democracy, open societies, the rule of law, human rights.” However, Europe, the world’s second-largest economic market, can only ensure its leverage in setting such an agenda by making some long-overdue changes.

First, European Allies must contribute their “fair share” to the collective defence aspirations of NATO in order to reassure the United States of its return on investment in the alliance. Of the 28 NATO member states, only five currently meet an alliance-wide threshold of contributing at a minimum two percent of a country’s GDP towards defence. In the United States, frustration with Allies for their lagging contributions to NATO capabilities is not a partisan issue. President Barack Obama repeatedly held the feet of his European counterparts to the fire for not meeting their obligations to the alliance. During his last year in office, he reminded the Allies that “free-riding” was not a sustainable policy option. If the alliance is to meet the threat posed by global terrorism or to rebuff Russian baiting along NATO’s eastern flank, member states must put their money where their mouths are.

Second, European nations, now more than ever, need to pool and share their defence assets and restructure security bureaucracy across the continent to promote greater efficiency. The European Defence Agency’s November announcement of a dramatic increase in military spending is a promising sign, but in an age of domestic austerity, the EU and NATO must identify opportunities to collaborate on short- and long-term defence planning and create formal mechanisms that prevent redundancy of effort. Furthermore, European defence planners must work to curb the protectionism of national defence industries pursued by member states, particularly for matured, non-sensitive technologies; such behaviour hurts the military and economic competitiveness of the EU and its members in the long run.

European Allies must contribute their “fair share” to the collective defence aspirations of NATO

NATO, for its part, should stand firm in rebuilding Afghanistan and avoid the adventurism that led the alliance into Libya, an operation that allowed Europe to flex its military muscle but laid bare the bureaucratic inertia that undermined political stabilisation following Colonel Gaddafi’s death. A 2007 cyberattack on Estonia, attributed to Russian actors, and the purported Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections reflect an emergent challenge that can serve both to unite and modernise NATO. Robust investments in alliance-wide cyber defences, cyber intelligence, and retaliatory capabilities would afford NATO a niche competency that both deters adversaries and reassures vulnerable Allies, including the United States.

Third, despite Trump’s affinity for the Brexiteers, Conservative leadership in the UK should remain sceptical of what the hard-balling President, who suffers from a credibility problem at home and abroad, can actually deliver. For the foreseeable future, a post-Brexit UK has much to gain from its European partnerships. Continental Europe, for its proximity and cultural affinity, will remain the premier market for British goods. Moreover, the threats posed by terrorism, organized crime, and migration will require a recognition of mutual goals, the development of common strategies, and the application of shared values across the English Channel. As Prime Minister May reminded us during her roll-out plan this week, Brexit is a bid for the UK to leave the EU, not Europe altogether. The UK has a vested interest in helping avert turmoil on the continent. A collaborative relationship between the UK and the EU to achieve real solutions to the region’s myriad problems while respecting the rule of law, encouraging competitive markets, and ensuring transparent elections would set a meaningful precedent and strong defence against the nativist populism that has taken root across parts of the Western world.

Europe’s long history of resilience, innovation, and principled leadership gives cause for optimism

Europe, if it hopes to survive in its current iteration, will have to make some firm decisions in the coming months, as it contends with the wilful separation of one of its wealthiest members and pro-Russian cheerleading from the U.S. President. Prioritising security and defence sectors will go a long way to allay the hesitations that threaten further disintegration of the EU and increased isolation from the United States. Notwithstanding these risks, Europe’s long history of resilience, innovation, and principled leadership gives cause for optimism that the region will meet the challenge before it—and, all the while, serve as a bulwark against illiberal politics that threaten the Western order, even those bubbling forth from the very country that orchestrated its post-war design.

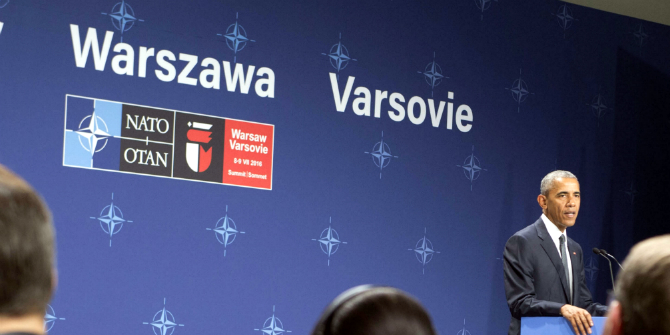

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Brexit, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Ash Carter (Flickr, CC BY 2.0).

Paul Angelo is a PhD Candidate at the Institute of the Americas, University College London and a Lieutenant Commander (select) in the U.S. Naval Reserve. During his active duty service, he served in a variety of roles in the European theatre, to include a post focused on NATO strategic communications. He previously earned an MPhil in Latin American Studies from the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and worked for the Council on Foreign Relations as an International Affairs Fellow from 2015 to 2016. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. government.

The liberal order is over and good riddance to it.

From the imposition of a disastrous multi cultural social experiment here at home and the imposition of censorship in some EU countries, to the mass immigration into Europe by Merkel, it has been a disaster.

President Trump owes the EU nothing and the UK needs to develop its own relationship with him, as must the EU. We are leaving the EU and having mutually beneficial trading relationships with the EU, does not include chaining ourselves to the EUs continuing disastrous policies.