Although Theresa May wants a bespoke deal with the EU that will be outside the European Free Trade Association, EFTA’s own relationship with the Union is instructive, write Sieglinde Gstöhl (College of Europe) and Christian Frommelt (Liechtenstein Institute). It sheds light on the challenges of an ‘arm’s-length’ relationship with the EU, in particular for trade policy.

In her Florence speech in September, Theresa May reiterated the UK government’s desire to negotiate ‘a deep and special partnership’ with the European Union. This appears to be located somewhere between a Canadian-style free trade agreement (FTA) and membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), the EU’s most far-reaching single market association with neighbouring countries. The UK is not seeking an ‘off-the-shelf’ model, but wants to ‘be creative’ in designing a model ‘which respects the freedoms and principles of the EU, and the wishes of the British people’.

Despite the UK’s desire for a bespoke deal, taking a closer look at the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) – of which the UK was a founding member in 1960 – helps to assess the prospects of tariff-free, frictionless trade with the EU and ‘the greatest possible access to the single market’, as May proclaimed in her Lancaster House speech. The EEA, and to lesser extent also the sectoral bilateral agreements between Switzerland and the EU, cover most of the UK’s interests. However, the experience of the EFTA states is at odds with the UK government’s ‘red lines’ of conducting an independent British trade policy; containing immigration to Britain from Europe; and taking back control of laws and the interpretation thereof.

EFTA’s experience has four lessons for trade policy

- EFTA allows its members to conduct an own trade policy vis-à-vis third countries, but it also offers the advantage of negotiating together in case of common interests.

- All the EFTA states considered a traditional FTA with the EU insufficient, and they were willing to align with EU rules by concluding agreements to ensure better access to the single market. In the EEA, the three EFTA states (Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) adopt relevant acquis on a monthly basis. Yet the practice of ‘autonomous adaptation’ in Switzerland shows that, due to its high economic interdependence with the EU, the projection of EU rules goes beyond formal agreements. In addition, Switzerland’s agreements on civil aviation and in the Schengen/Dublin association are based on the EU’s evolving acquis.

- The actual scope of the EU-EFTA relationship remains diffuse, since an EU act that becomes an integral part of the EEA may also cover policies that partly fall outside the scope of the EFTA states’ relations with the EU (for instance agriculture and fisheries linked to the free movement of goods). Moreover, the lines between the internal market and other parts of EU law (like fiscal policy, citizenship or internal security) have become increasingly blurred.

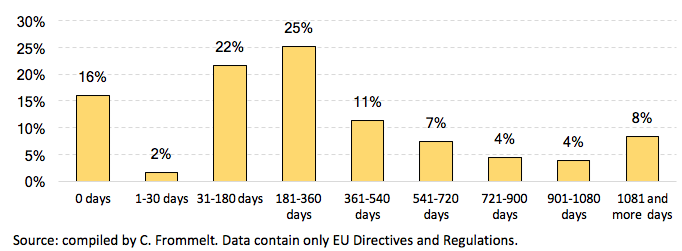

- Although the principle of market homogeneity enshrined in the EEA Agreement guarantees the EEA EFTA countries non-discriminatory access to the single market, they often take a while to incorporate laws, which can affect their ability to compete. For example, as the figure below shows, between 1994 and 2015 only 16 per cent of the 4573 legal acts incorporated into the EEA Agreement had the same compliance dates in the 31 EEA countries. For all other new legal acts, different sets of rules applied for the citizens and businesses in the EU and the EEA EFTA states. This can hamper legal certainty and temporarily lead to competitive advantages or disadvantages. In practice, these effects are often neglected given the small size of Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. In the case of the much bigger UK, however, different rules may easily affect the smooth functioning of the EU’s internal market.

Share of incorporated EU acts with different compliance dates in the EU and the EEA (1994-2015, N=4573)

What lessons can we draw from EFTA’s participation in the free movement of people?

- Freedom of movement is part of an overall balance of benefits and obligations, and emphasises the importance of non-discrimination. Full participation in the single market without free movement of people is not a realistic option for the UK. Furthermore, the EU would expect a financial contribution to reduce economic and social disparities in the EU which is proportionate to the benefits that a country draws from its participation in the single market.

- The actual scope of freedom of movement of may differ slightly between the EU and a case of external differentiation such as the Swiss model, but would still include the free movement of workers, students and economically inactive people, the freedom of establishment, family reunification, or the coordination of social security systems.

- Liechtenstein’s special arrangement in this area is closely linked to its very small territory and unusually high share of foreigners, and is therefore not a precedent for the UK to follow.

What are EFTA’s lessons for the institutional architecture of the UK’s future relationship with the EU?

- The ‘Interlaken principles’ which the EU set out in the late 1980s are still valid: priority has to be given to the deepening of the EU’s own integration and the preservation of its decision-making autonomy. The EEA Agreement grants EEA EFTA states only a limited participation in the so-called ‘decision-shaping’ phase of EU policy-making, which is more about gathering information than exerting political influence.

- The EU insists on a balance of benefits and obligations in each partnership and is afraid of setting any precedents that could trigger more demands from other non-members.

- The EEA would still require full free movement of persons and come with the jurisdiction of the EFTA Court.

- Any close economic association with the EU based on its acquis requires a satisfactory mechanism through which the third countries keep up with the evolution of the acquis in order to safeguard market homogeneity. There is an inherent trade-off between the benefits resulting from the single market and the lack of participation in the law-making process, which also leaves little room for parliamentary control.

- As we describe above and in our longer article, even the highly institutionalised EEA suffers from shortcomings, such as an inconsistent selection and a delayed incorporation of new law.

These lessons confirm the principles set out in the EU guidelines for the Brexit negotiations: the integrity of the single market with its four freedoms and the autonomy of the EU’s legal order and decision-making process. The UK is well aware of these principles, but hopes that its unprecedented point of departure as an EU member may provide the basis of a bespoke model. However, the experience of the EFTA states shows that the real challenge of European integration is not to converge with EU law but to prevent a growing divergence. In this regard, the institutional set-up of external differentiation is a necessary but not sufficient condition of effectiveness.

Specific characteristics of the EEA EFTA states, such as their small size, strong economic interdependence with the EU and high state capacity, are likely to mitigate the constraints resulting from the institutional complexity of the EEA’s two-pillar structure. Yet the fact that the speed of incorporation differs greatly across EU acts shows that specific properties of the acquis may also delay incorporation. For instance, an EU act may bestow the competence to take binding decisions on an EU agency. Before such an EU act can then be incorporated into the EEA Agreement, it first has to be decided which institution(s) will be competent for the EEA EFTA states, and specific adaptations to the act have to be agreed. Indeed, for every relevant EU act, an assessment of its compatibility with the EEA’s institutional framework has to be carried out as well as an assessment of the compatibility of any specific EEA adaptation with the goals and obligations set out in the EEA Agreement.

The future partnership papers published by the UK government so far suggest that, for issues such as customs or data protection, it intends to operate a regime that aligns closely with the respective EU acquis. However, the papers still lack details about the institutional framework for alignment, enforcement and dispute resolution. If the UK were to insist on its three ‘red lines’, a ‘hard’ Brexit in the form of a limited, FTA-based model would be the logical result.

Membership restricted to EFTA only – either full or via an association – would meet all three British ‘red lines’, but unlike the other EFTA countries Britain would have no access to the EU’s single market. The UK would still have to negotiate its future relationship with the EU. Consequently, EFTA membership or association alone would be of limited value to the UK. Even if the UK government does not seek an ‘off-the-shelf’ model of the kind already enjoyed by other countries, but a unique British one, it cannot escape the lessons to be learned from EFTA as it negotiates ‘a deep and special partnership’ with the European Union.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Sieglinde Gstöhl is Professor of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies at the College of Europe, Bruges.

Christian Frommelt is Research Fellow in Politics at the Liechtenstein Institute, Bendern.