How will Brexit shape conflict resolution within and between EU member states? In this post, Johannes Karreth (Ursinus College) observes that Brexit may pose a challenge not only to peace in Ireland but also for disputes between the UK and other European countries, such as the recent Franco-British “scallop war”, that the EU has helped to keep at bay. He concludes that after Brexit there will be a great need for subsequent international agreements to make up for the loss of the EU institutional framework for conflict resolution and prevention.

How will Brexit shape conflict resolution within and between EU member states? In this post, Johannes Karreth (Ursinus College) observes that Brexit may pose a challenge not only to peace in Ireland but also for disputes between the UK and other European countries, such as the recent Franco-British “scallop war”, that the EU has helped to keep at bay. He concludes that after Brexit there will be a great need for subsequent international agreements to make up for the loss of the EU institutional framework for conflict resolution and prevention.

Debates about Brexit and political conflict most prominently relate to Northern Ireland and a possible resurgence of violence there, as has been previously discussed on this blog. But Brexit may pose a challenge not only for the continuing peace process in Northern Ireland, but also for disputatious issues between the UK and other countries that the EU has helped keep at bay for some time. As a highly structured international organisation with considerable leverage, the European Union can influence the consideration of political actors on opposite sides. Recent research provides some insight into how this influence has played out in a broader context and how Brexit could affect conflict dynamics in Northern Ireland and the UK’s foreign relations.

For Northern Ireland, Brexit-related concerns typically centre around the tightening of a post-Brexit border with Ireland, economic losses due to higher barriers to trade, and speculations about political realignments in a Northern Ireland with a stricter border to Ireland. But the EU has also played an important role in the peace process. EU funding, while perhaps not crucial, has supported various important initiatives around the peace process.

The European Union’s positive influence on the peace process in Northern Ireland, however, goes beyond the border and the direct impact of EU-funded programs. My recent research shows that highly structured international organisations – of which the EU is one example – become an important actor shaping the choices of conflict parties, in civil wars and interstate disputes alike.

The European Union’s self-declared goal is to promote peace, and the EU has a multitude of tools to work toward this goal. Beyond these active efforts, the EU is also one of a small number of highly structured international organisations with economic leverage over member states. This leverage comes from the economic benefits that members can derive from the organisation – and the losses that a suspension or cessation of membership might bring. In the case of Northern Ireland, the EU has allocated about EUR 3.5 billion for each of the 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 budget periods.

Why are these funds relevant for peace in Northern Ireland? One can argue that they benefit economic development and reduce grievances that might otherwise stimulate conflict. But political science research also emphasises that third-party actors with leverage have a notable influence on the costs and benefits that governments and opposition groups face during severe political disputes. Escalation of political disagreements to violence will lead to a disengagement of highly structured IGOs and withdrawal of their staff, resources, and other benefits. Yet, highly structured IGOs also carry the promise of rewards for keeping the peace by providing substantial resources and benefits conditional on the absence of further violence – as the EU has done in Northern Ireland. This provides a crucial commitment device to settle conflicts and avoid their recurrence.

The evidence suggests that the engagement of highly structured IGOs in member countries is associated with a substantial decline of the risk that political conflicts escalate to civil wars. Since World War II, roughly one-third of more than 260 separate low-level armed conflicts have escalated to civil war. But conflicts in countries with more connections to highly structured IGOs faced a considerably lower risk of escalation, reduced by up to a half. The figure below, created based on statistical analysis, highlights this pattern.

In the case of Northern Ireland, leaving the EU would mean that severing ties with the EU itself – a powerful, involved highly structured IGO with considerable leverage in this case – and several other EU-related institutions might reduce the commitment of political actors to the peace process. In the absence of powerful incentives for keeping the conflict at bay, taking steps toward possible provocation and escalation face lower costs. Projecting statistical findings from all cases of lower-level armed conflicts since 1946 on a post-Brexit Northern Ireland, losing EU-based commitment devices would substantially increase the risk that a flaring up of political tensions might escalate to more serious violence.

But the EU’s role as a commitment device is not restricted to internal political conflicts. It also extends to interstate disputes, as my research and that of other scholars suggests. Of course, promoting peace was a key purpose shared by Winston Churchill and other leaders who founded the EU.

Of the many dimensions of EU efforts to maintain peace between European states, the role of the EU as a commitment device has shown to be important. Organisations with high economic leverage (such as the EU) help set up clear costs for escalating political disputes. Knowing these costs in advance as well as benefiting from membership in the present sets up incentives for states to keep disagreements from turning violent. In this sense, organisations with high economic leverage enjoy an advantage compared to organisations other types of peace-promoting features (such as conflict resolution panels or efforts to promote shared identity).

Evidence for this assessment comes from analyses of several hundred claims that states have made against each other and political crises between states since 1945. I find that states that were subject to the economic leverage of more international organisations (again, the EU and other organisations with similar leverage features) were substantially less likely to take steps to escalate claims and crises toward using military force. Concerns about maintaining benefits from organisational membership feature prominently in these states’ calculations. Anecdotal evidence from a debate in the House of Lords on a fishing dispute supports this assertion.

Potential disputes involving a post-Brexit UK and current EU members are not a made-up scenario. British and French fishermen recently clashed over a dispute over scallop stock. Gibraltar proves a difficult-to-navigate issue in British-Spanish relations. In both cases, the leverage of the EU has discouraged states from escalating potential disputes. Mediation and other support from the EU have also helped. Without the firm leverage of the EU, the incentives for the British government and its counterparts are different. If a larger list of disputes around the world can be a guide, these changed incentives may make claims over fishing stock or territory more intractable.

Recognising the importance of incentives, the EU has proposed to continue funding efforts even after Brexit to promote peace in Northern Ireland. In contrast, some speculate that Brexit and the separation of access rights might resolve the “scallop wars”. But if research is any guide, the promise of institutional arrangements within the EU is their reliability and relative consistency. Agreements after Brexit, whether they concern peace in Northern Ireland or disputes over territory or fishing stock, will need to make up for the loss of this institutional framework to resolve commitment problems.

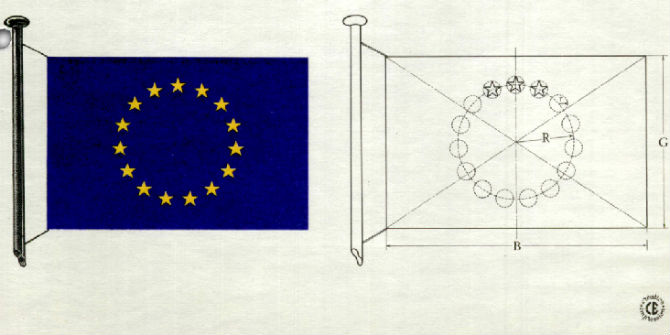

This post represents the views of the author and neither those of the LSE Brexit blog nor of the LSE. Image by Larry Smith, Some rights reserved.

Johannes Karreth is Assistant Professor of Politics and International Relations at Ursinus College near Philadelphia, USA. His book “Incentivizing Peace: How International Organizations Can Help Prevent Civil Wars in Member Countries” (co-authored with Jaroslav Tir) is available from Oxford University Press, and his article “The Economic Leverage of International Organizations in Interstate Disputes.” recently appeared in International Interactions.

What an amazing result for Putin that would be. Control of the USA, influence across the Middle East via Syria, and the rest of Europe all fighting each other instead of becoming (because the have never been yet) a united block of countries who are the only ones left to stand in the way of Putins greed and ambitions.

Surely the scallop war was actually caused by shoddy EU legislation?

Times change and countries move on.

The EU maintains Hard Borders which adjacent countries have to accept.

Not everyone likes change especially when it inconveniences them. However Sovereign nations do have to protect their borders and NI border structure will change to enable adequate security. There is no danger to life in a hard border other than a non acceptance by people who are warlike in their wish to achieve change or maintain the status quo.

In order to protect Sovereign territory violence would be needed to repel violence. People who live in democracies should abide by the processes, change them without violence or suffer the consequences of their actions. One unfortunate trait of most of the the UK people is that we react only after severe provocation.