London has been accused of dominating UK political, economic and cultural life for hundreds of years. However, the last decade has seen relations become increasingly strained, with a series of seismic events inflaming longstanding tensions between the capital and the rest of the nation. In the third of the London Calling Brexit series, Jack Brown (Centre for London) looks at how the rest of the UK view their capital city.

London has been accused of dominating UK political, economic and cultural life for hundreds of years. However, the last decade has seen relations become increasingly strained, with a series of seismic events inflaming longstanding tensions between the capital and the rest of the nation. In the third of the London Calling Brexit series, Jack Brown (Centre for London) looks at how the rest of the UK view their capital city.

From the financial crash and the austerity that followed it, to the expenses scandal and two divisive referendums, London’s two ancient cities – the City of Westminster and the City of London – have been at the centre of much of the controversy. And the nation has noticed: as Ipsos MORI’s most recent Veracity Index suggests, Fleet Street, SW1 and the Square Mile are currently the national centres of some of the least trusted professions in the country.

Policy initiatives from central government such as the Northern Powerhouse, HS2, or the recent commitment to move Channel 4 out of London all speak to a desire to ‘re-balance’ the national economy away from London and the South East. That the capital was the only English region to vote to Remain in the 2016 EU referendum only served to highlight how different many feel the capital is becoming from the rest of the nation.

Some have blamed an out of touch ‘liberal metropolitan elite’, overwhelmingly concentrated in London or Westminster, for Brexit and the climate that led to it. These accusations have been most prominent, perhaps ironically, amongst equally ‘elite’ politicians and commentators in equally powerful positions, often based in London themselves. But is there really a more widespread feeling in the rest of the country that the capital and the rest of the UK are moving apart?

Do Leavers hate London?

Opinion polling has heavily suggested that the British public think that the UK is too centralised in Westminster and Whitehall – and that London benefits from unfair treatment as a result. A 2014 Survation poll found just under two-thirds of UK adults agreeing that ‘too much of England is run from London’, and over 70 per cent agreeing that, as a result, ‘London gets preferential treatment over most other parts of the UK’. Polling by the Centre for Cities and Centre for London, conducted shortly afterwards, also found a majority of non-Londoners felt that the UK government was too London-centric.

But perhaps resentment of the capital runs deeper than its association with national government. In 2014, amidst the rise of UKIP, the journalists John Harris and John Domokos travelled the country, interviewing the public outside of the capital for their ‘Britain’s in Trouble’ video series. They reported that relations had become ‘toxic’, with London viewed as ‘a city-state, with a different way of life, a different culture’. Ultimately, for many, ‘the symbol of most ills [was] seen to be London.’

Two referendums on the UK’s constitutional future later (one in Scotland and the other across the UK on the matter of Brexit), and Centre for London has conducted its own polling to test how perceptions of London have changed. But the polls also picked up differences in how Remain and Leave voters see the capital. Whilst these differences were smaller than one might expect – which should give some grounds for optimism – they are consistent enough to be revealing of the differences between Leavers and Remainers, and offer some clues as to how Brexit may affect how the capital is perceived.

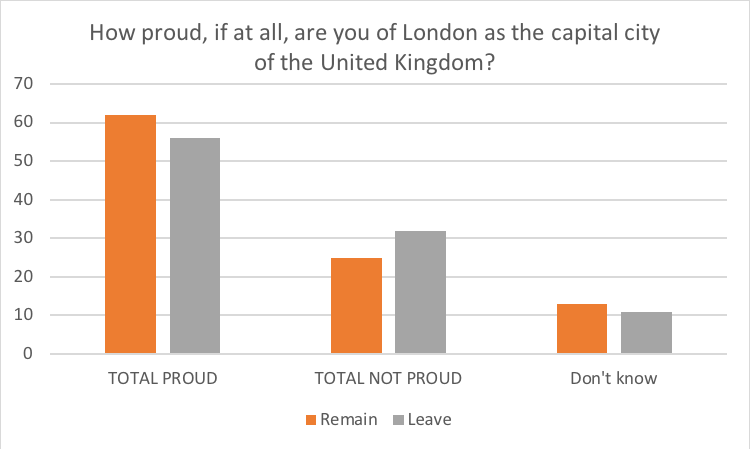

Firstly, there is the question of overall pride in the capital. Leavers were less likely to express pride in London as capital city of the UK than Remain voters. However, for both groups, a majority of people still said that they were proud of London as a capital. This included 51 per cent in the North of England, and an average of 59% across England only. So whilst there are differences in opinion along Brexit lines, these are far from terminal.

There were also differences between how Remain and Leave voters described London as a place. Leave voters appear to hold more negative views of London overall. Asked to choose from a list of words to describe the capital, they were more likely to choose words like ‘expensive’, ‘crowded’, ‘chaotic’, ‘dirty’ and ‘impersonal’ to describe London, and less likely to choose words like ‘diverse’, ‘cultural’, ‘lively’ or ‘dynamic’. These gaps are also small but consistent: whilst their consistency suggests that there is an issue, their size suggests that the issue is far from irreparable.

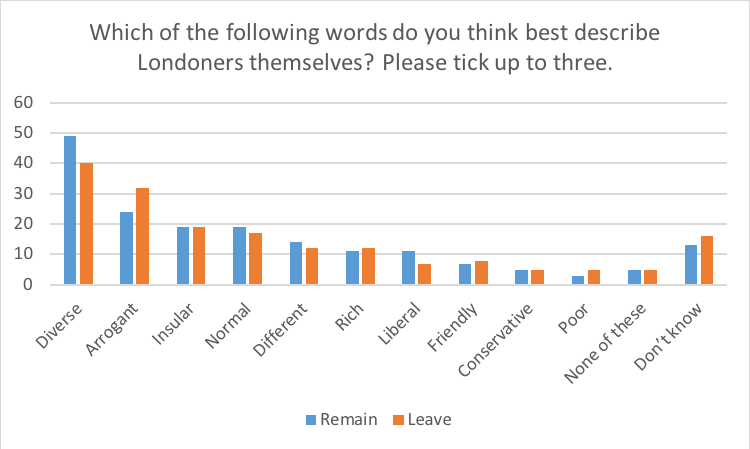

Asking non-Londoners to pick words to describe Londoners themselves produced more mixed results, with one interesting exception. The two most popular words split on a Remain-Leave basis, with Remainers more likely to describe Londoners as ‘diverse’ than Leavers were, and Leavers more likely than Remainers to think the capital’s residents ‘arrogant’. Leave voters were also less likely to use the word ‘liberal’ than Remain voters to describe Londoners. Perhaps the ‘liberal metropolitan elite’ is more self-conscious than it needs to be.

Wider perceptions of London

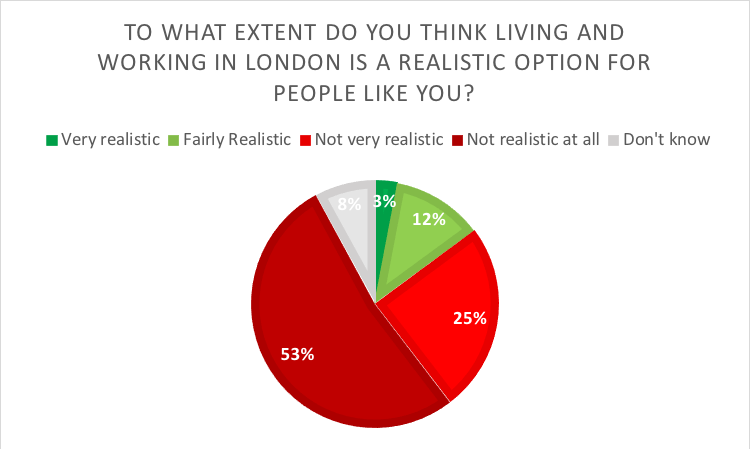

The key to all of this may lie in the fact that, outside of the capital, London is seen as remote and inaccessible by both Remainers and Leavers alike. A sizeable majority (78 per cent) of non-Londoners thought that living and working in London was ‘not very realistic’ or ‘not realistic at all’ for ‘people like them’. The prevalence of words like ‘expensive’ and ‘crowded’ in describing the city, alongside descriptions of Londoners themselves as ‘insular’ and ‘arrogant’, was notable regardless of EU Referendum vote.

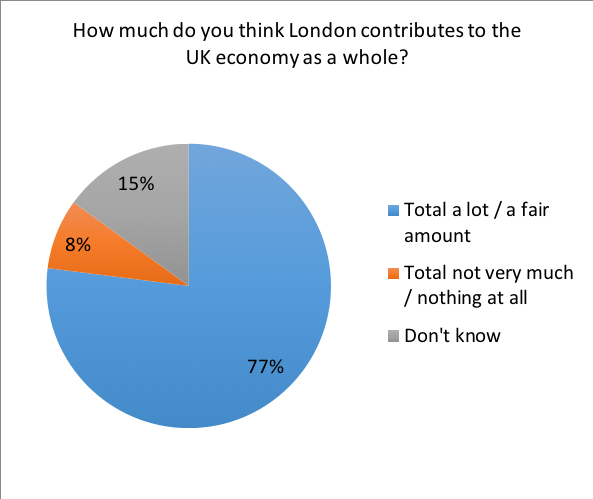

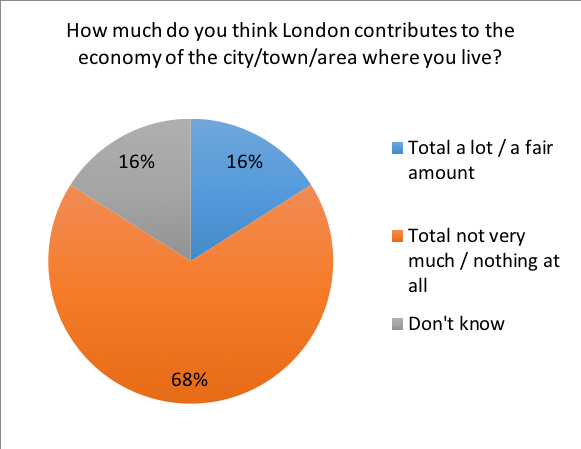

In addition, whilst over three-quarters of non-Londoners agreed that London contributed either a lot or a fair amount to the UK economy, only 16 per cent felt that London contributed to the economy where they live. So whilst London’s economic contribution is accepted as a positive in an abstract sense, this is not translating into visible progress outside of the capital.

The UK’s post-Brexit future is still extremely unclear. But the government’s own forecasts predict that Brexit will have a much stronger negative economic impact outside of the capital, regardless of the outcome of the ongoing negotiations. London is expected to take the smallest hit to economic growth in the country, across all post-Brexit scenarios. There is also some uncertainty amongst regional leaders over how EU regional subsidies will translate into the UK-administered ‘shared prosperity fund’ after Brexit. It seems highly unlikely that there is any scenario that will not make these economic disparities worse, at least in the short term.

What to do about it?

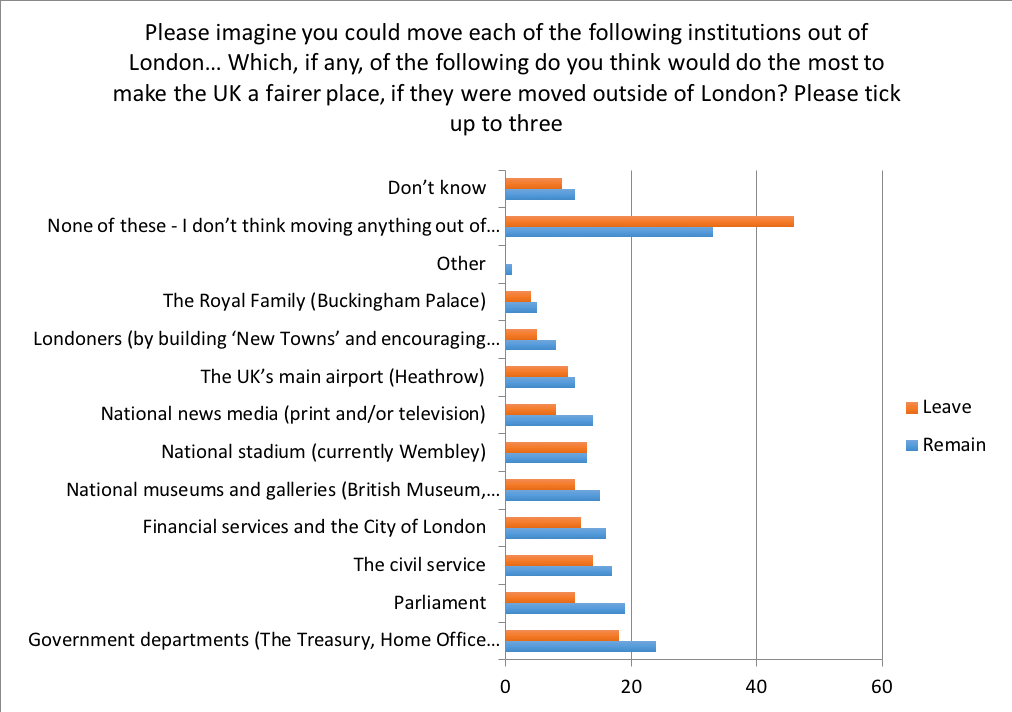

Perhaps most surprisingly, despite their distaste for London as a place, (not to mention that their referendum vote is often interpreted as a rejection of the status quo and a desire for change), Leave voters are notably more likely than Remain voters to want to keep things where they are in the UK. Both Remain and Leave voters were particularly disinterested in ‘decentralising’ the country to make it ‘fairer’, by moving institutions such as Parliament, government departments, the national news media or national museums and galleries out of London. But Leave voters were even less interested.

Overall, it does appear that Leave voters are more likely to hold negative views of the capital than Remain voters. They are less likely to express pride in London, more likely to pick negative words to describe it, and more likely to view its occupants as ‘arrogant’. These differences are small, but are consistent enough to suggest a pattern. The size of these differences also suggests that this is not unsolvable. However, Leave voters are also less inclined to take radical action to address London’s dominance by moving institutions out of the capital. Squaring this particular circle will be an important aspect of post-Brexit national policymaking in the UK.

Brexit is perhaps both a symptom and a cause of the disjunct between the capital and the rest of the UK – as well as between cities and towns, the North and the South, between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and countless other nuances. The United Kingdom is a far from homogenous place, and a binary referendum leaves little space for nuance. Yet whilst it could be said that the EU Referendum was, at least to some extent, a wake-up call to the ever-widening economic and cultural gap between London and the rest of the country, the process of negotiating Brexit has, ironically, left little space for serious thinking about how to address the issue. On top of this, every possible Brexit permutation is predicted to exacerbate, rather than improve, spatial inequalities in the UK.

However, Brexit also brings opportunities for improving intra-UK relations. Whilst there is a widespread sense that progress on devolution has stalled, with Westminster and Whitehall preoccupied by Brexit, there is nevertheless a need to find the time to re-think how the nation is governed, and how to better connect those feeling disillusioned and the disengaged with power on a local level. Whilst there are Leave-Remain gaps in perception, they are not so large as to be insurmountable. Efforts to rebuild good relations between London and the rest of the UK will be vital if Brexit is to result in a more ‘United’ Kingdom – and they can, and must, be made.

All figures, unless otherwise stated, are from YouGov Plc. Total sample sizes were 1218 in London and 1883 in the rest of GB. Fieldwork was undertaken between 3-6 September 2018. The survey was carried out online. The figures have been weighted and are representative of London adults and GB adults outside London (aged 18+) respectively. YouGov are a member of the British Polling Council and abide by their rules. The rest of GB data can be found here and the London data here.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Brexit or the London School of Economics.

Jack Brown is a Senior Researcher at Centre for London.