Despite a few more women making an appearance in the TV referendum debates, the campaign continues to be dominated by male ‘experts’ and a presumption that women will vote on the basis of emotive issues of special interest to them, such as maternity leave policies, write Toni Haastrup, Katharine Wright and Roberta Guerrina. But true gender equality considers the impact of social policy on every part of society. We can and must challenge the perception of “high” and “low” politics that marginalises particular discussions and effectively sidelines women.

With days to go until the referendum, the campaigns are going all out to capture the votes of the undecided. As women are still more likely to say they are undecided about voting intentions, we could expect the campaigns to rank up their efforts to capture ‘the women’s vote’.

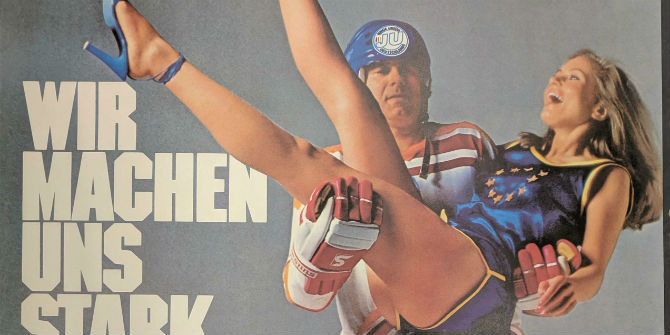

Women political leaders have become more visible in campaign events, and the second ITV debate was female dominated, in as far as it showcased five women who are key figures in the campaigns. This is the first time that we have seen women taking the lead in discussion about high politics – the economy, security and migration – during a prime-time slot. Prior to this, and in the week following the ITV debate, women’s contributions have concentrated once again on which political institution is best placed to safeguard maternity rights, equal pay, and women’s human rights, thus implicitly equating women’s interest in the referendum with gender equality policies – in other words, “low” politics.

Conversely, issues pertaining to “high” politics – security and defence, and the economy – have remained squarely the prerogative of men. As a result, where women’s voices and expertise have been included, it has been to speak about social politics and policies. Moreover, there has been no meaningful attempt to bridge the gap between high and low politics areas or to engage meaningfully with what the ‘women’s vote’ means in respect to the upcoming referendum.

Male:female expert ratio: 2.9:1

Research from City University has demonstrated that the EU referendum debate reflects wider, and fairly entrenched trends, in the way women’s expertise is frame and often undervalued. Lis Howell’s study found on average 2.9 male experts for every one female expert across primetime news on a number of outlets (BBC News, Channel 4 News, ITV News, Sky News and the Today programme). As Howell points out on BBC Radio 4’s Media Show, part of the issue stems from a preoccupation with getting the ‘top expert’, which is usually conflated with getting the top man. There is also the issue that these programmes address “high” politics issues, not those perceived to be of interest to women or the issues on which women are expected to have expertise.

Women’s rights issues remain a key area of contestation for feminist activists, so it is important to talk about these issues in relation to the EU referendum, particularly in view of the contention that historically the EU has been a positive force in the development of (women’s) employment rights. However, it is difficult to see how such a blatant instrumentalisation of core feminist issues can help to close the gender gap in women’s political participation. Rather, this approach only serves to marginalise women further as it fails to address the underlying reasons why women’s voices are largely absent or marginal within this campaign.

The emotive sphere

Understandably, both the Brexit and Bremain camps are quick to want to link their own particular campaign to the emotive sphere, which has long been recognised to be directly linked to the construction of identity. In doing so, however, they reinforce harmful stereotypes about women; they are implicitly sending a message to the wider public: women cannot be trusted with decisions about “high” politics based on evidence. Rather than mobilise women and increase participation and engagement, it may well increase disaffection and decrease perceptions of efficacy amongst this demographic group.

Conversely, research has shown that women are actually socially groomed to consider a broad range of evidence when weighing options. They are less emotional than men when making important decisions that affect their future. Why then do we infantilise women by confining their agency to ‘women’s issues’? On both sides of the political aisle in this referendum debate, women are being asked simply to consider what side is best for them in terms of maternity rights, or in terms of the fight against female genital mutilation. Where these things do not apply to them, they seem to be left out of the debate and inevitably silenced. While maternity leave and issues around Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), for example, impact directly on women, they should be the concern of all. This is what it means to work towards a gender equal society – a society where women are not marginalised and so-called women’s issues are important enough to be everyone’s issues.

The campaign on both sides should accept the core principle that underpins a wider commitment to gender mainstreaming, which asks us to consider the gender impact of all policy areas. This is the commitment that is part of the Gender Equality duty. It should not be a stretch to think that a commitment to understand the asymmetrical impact of a policy on men and women, also requires us to think about the way we conduct political campaigns.

We can and must do better

We can do better! If we seek to engage traditionally marginalised groups, which does not mean women are a minority group, we can develop into a mature polity that considers key issues and makes decision on the basis of evidence, rather than soundbites. Moreover, building an inclusive political community will help to transform political institutions and challenge traditional binaries, such as “high” vs “low” politics.

Failing to engage with traditionally marginal groups and maintaining a fractured political culture that sideline core constituencies that gives a voice only to elite white men is simply not acceptable. With perhaps the single most important vote in a generation next week, we – as a political community, of academics, politicians and the media – can, should and must do better!

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the BrexitVote blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Roberta Guerrina is Reader in Politics and Co-Director of the Centre for Research on the European Matrix (CRonEM) at the University of Surrey. She is author of Mothering the Union (Manchester University Press) and researches gender politics in the EU, the politics of mothering, and the feminist approaches to security studies. She has written about gender and Brexit for LSE BrexitVote.

Toni Haastrup is Lecturer in International Security and a Deputy Director of the Global Europe Centre at the University of Kent. Her research interests include EU security and development policies especially in Africa, the gendered dynamics of institutions and feminist security studies.

Katharine A. M. Wright is a Research Fellow working on the ESRC’s “UK in a Changing Europe” programme. She is also a Teaching Fellow in International Politics at the University of Surrey. She works on issues of gender and European security, focusing in particular on NATO and the EU.

6 Comments