Regional economic differences within Italy will not be reduced simply by building infrastructure, tackling organised crime or increasing productive investment in the South: people’s norms of cooperation need to change too.

That is the central finding of a series of economic experiments. Our study involved nearly 700 ordinary citizens from the North and South of Italy, who were presented with a situation with real money at stake in which they could choose whether or not to trust anonymous citizens living in the same city. Some participants in the experiments were endowed with an amount of money by us and were invited either to keep it or to pass it to others. If they passed it on, we would triple the money and the receivers could return a portion of it, at their complete discretion, to the giver.

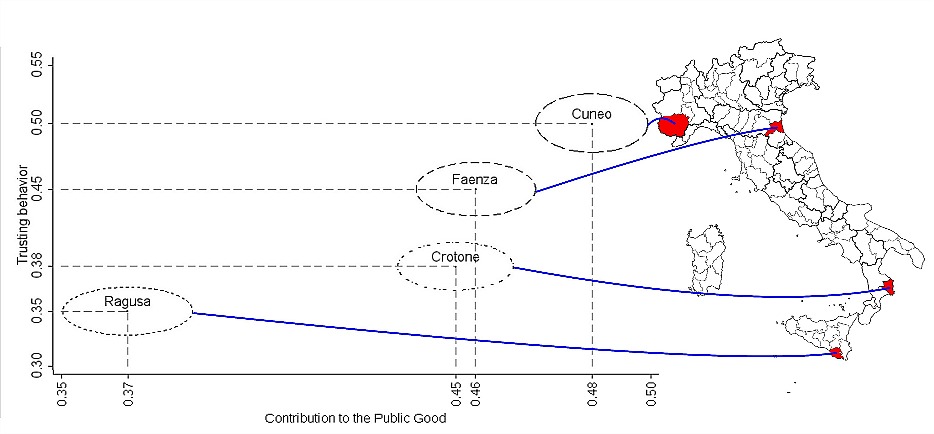

We found that people living in Cuneo, a mid-size city in Piedmont trusted 50 per cent of the time, while people living in Ragusa, Sicily, trusted only 35 per cent of the time. This proves that there is a regional difference in collaborative norms.

Similar findings were replicated also for a situation where individuals can contribute to a group project that would double the contributions and distribute them equally among all group members (public good in Figure 1), which confirms the robustness of a gap between North and South of Italy in norms of cooperation.

Figure 1: Cooperation levels across Italy

But we also find that the two macro-regions are similar in terms of individuals’ generosity and tolerance for financial risk. This suggests that the regional divide may be related less to individual characteristics than to the way individuals interact in groups. This evidence contrasts with one of the best-known interpretation of Edward Banfield’s book The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. Banfield claimed that the origin of the North-South gap in Italy lies in the moral flaws of Southerners, whose only concern is with their personal welfare and that of their families with utter disregard for anyone else.

The new study provides something that has been missing from the debate on the cultural roots of regional divide: a solid empirical basis. We travelled with a mobile laboratory in a van across Italy and carried out an original measurement, obtained through field experiments with incentives for participants. We documented the field work in a short video available here:

The study presents high quality data based on actual behaviour in an environment where a host of confounding factors can be controlled for. For the first time this methodology is applied to North-South differences in the ability to cooperate. It makes it possible to test whether regional differences survive even when incentives are held constant. Since regional disparities still emerge in response to otherwise identical experimental conditions, the implication is that the root of the North-South divide cannot be simply attributed to differences in incentives, but is rooted in differences in beliefs and preference traits.

Traditional explanations of Italy’s North-South divide, such as that in the 1884 Jacini Inquiry*, have focused on incentives, ranging from geographical and structural problems (for example, distance from Northern Europe, lack of proper roads), inefficient land property institutions (for example, latifundia), rent-seeking informal institutions (for example, political patronage, the mafia) and counterproductive economic policies, which destroy people’s motivation to work hard, invest and innovate.

Instead, this study argues for the existence of an important cultural component. This approach shares many aspects with Robert Putnam’s book Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Putnam called into question collective dispositions towards cooperation and good government, as measured by regionally varying levels of social capital. However, the individual pro-social choices recorded in the field are not correlated with the proxies for social capital that are widely used as measure of civicness. Hence, the new study shows that proxies of social capital cannot explain the behavioural gap in the ability to cooperate in Italy.

| * The Jacini Inquiry |

|---|

| It is a report following the extensive inquiry about the conditions of the agricultural sector and the farmers in Italy promoted in 1877 by the Italian Parliament. Stefano Jacini presided a commission who performed the inquiry and in 1884 delivered its conclusions on the difficult conditions of the rural population, affected by malnutrition, child labor, illiteracy, and humiliating working conditions. It provided for the first time an encompassing description of the situation in the field of the different Italian regions, especially the Southern regions, after the 1861 Unification for the use of a ruling class that originated mainly from the North of Italy. The report is structured in regional sections that fills several volumes. Although it constituted the grandest inquiry up to that time on the rural economy, it had no political impacts on the reform agenda. |

| Source: Jacini, S. (1884). Atti della Giunta per la inchiesta agraria e sulle condizioni della classe agricola, no. v. 15,pt.1 in Atti della Giunta per la inchiesta agraria e sulle condizioni della classe agricola, A. Forni. |

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post is based on the authors’ paper Amoral Familism, Social Capital, or Trust?, Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society (RES), June 2016.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Street in Rome, Italy, by Veronidae (own work) under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence, via Wikimedia Commons

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Maria Bigoni is Associate Professor at the University of Bologna. She has conducted extensive experimental work with a focus on industrial organization, information acquisition and learning, incentive mechanisms, and cooperation among strangers in repeated games.

Maria Bigoni is Associate Professor at the University of Bologna. She has conducted extensive experimental work with a focus on industrial organization, information acquisition and learning, incentive mechanisms, and cooperation among strangers in repeated games.

Stefania Bortolotti is a Post-doctoral Scholar at the University of Cologne. Her main research interests are in experimental and behavioural economics, with a focus on issues of coordination and cooperation.

Stefania Bortolotti is a Post-doctoral Scholar at the University of Cologne. Her main research interests are in experimental and behavioural economics, with a focus on issues of coordination and cooperation.

Marco Casari is Professor of Political Economy at the University of Bologna. He holds a Ph.D. from Caltech and had appointments at Purdue University, Ohio State University, and the Autonoma University of Barcelona. Besides experiments, he has also carried out field studies on the community governance of the commons in Medieval and Modern Italy. marco.casari@unibo.it

Marco Casari is Professor of Political Economy at the University of Bologna. He holds a Ph.D. from Caltech and had appointments at Purdue University, Ohio State University, and the Autonoma University of Barcelona. Besides experiments, he has also carried out field studies on the community governance of the commons in Medieval and Modern Italy. marco.casari@unibo.it

Diego Gambetta is Professor of Social Theory at the European University Institute, Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford, and an official fellow at Nuffield College. He applied economic theory and a rational choice approach to understanding a variety of social phenomena, such as the Sicilian Mafia, trust, and suicide extremists.

Diego Gambetta is Professor of Social Theory at the European University Institute, Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford, and an official fellow at Nuffield College. He applied economic theory and a rational choice approach to understanding a variety of social phenomena, such as the Sicilian Mafia, trust, and suicide extremists.

Francesca Pancotto is Associate Professor at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. She has an interest both in experimental and behavioural economics as well as in financial economics.

Francesca Pancotto is Associate Professor at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. She has an interest both in experimental and behavioural economics as well as in financial economics.