Employment in the European Union is still falling short of the objectives set by the continent’s leaders more than 10 years ago. Nobel laureate Chris Pissarides explains why Europe remains behind the United States in job creation, particularly in business services and the health and education sectors.

Employment in the European Union is still falling short of the objectives set by the continent’s leaders more than 10 years ago. Nobel laureate Chris Pissarides explains why Europe remains behind the United States in job creation, particularly in business services and the health and education sectors.

The European Union’s targets for employment, set at the Lisbon summit of 2000, have not been met by all member states. The Mediterranean countries in particular have failed to achieve the objective of getting at least 70% of the working age population into employment. And the jobs performance of the continent as a whole continues to lag behind the United States. What is the future of work in Europe?

One way to answer this question is to go behind the aggregate figures and compare which sectors are creating jobs. The transatlantic comparison is interesting for two reasons. First, the United States is still the technologically most advanced country and a leader in developing new kinds of jobs and new sectors of economic activity. Think of Silicon Valley and the dot.com boom.

Second, had Europe’s performance followed the United States more closely over the last 30 years, the employment ambitions of European leaders would have been met. But the employment histories of the two continents deviated, starting sometime in the early to mid-1970s. To make the argument more concrete, consider the two continents in the period just before the Great Recession of 2008-09. In the first eight years of the 2000s, more than three quarters of Americans but only two thirds of Europeans aged between 15 and 64 were in employment. Coupled with higher American enrolment rates in higher education, this shows that a lot more Americans were active outside the home than their European counterparts.

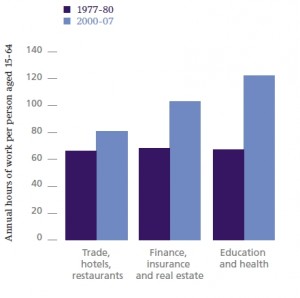

Looking deeper into the transatlantic employment gap, three broad sectors account for virtually all the differences (see Figure 1). First, services that are provided directly to the public, such as retailing. Second, services that are mainly business to business, such as finance, insurance and commercial property And third, services related to health and education, which are mostly for self-preservation and self-improvement.

Figure 1: The gap in annual hours between the United States and the eurozone in three industrial sectors

In the late 1970s, the annual hours of work in each sector in the United States exceeded those in the eurozone countries by about 70 for everyone aged between 15 and 64. But by the early 2000s, the extra hours worked annually by Americans had jumped to 120 in health and education, 100 in business-to-business services and nearly 80 in services provided to the public. Moreover, most of the US gains were in health, retailing and a general ‘business services’ sector that includes accountants, management consultants and expert advisers.

Why are Europeans not creating enough jobs in these sectors? Take retailing. Most people who have been shopping in the United States know that it is a lot easier to get assistance in American shops than European ones. Economists attribute these differences to taxation and regulations that make employing retail assistants more expensive in Europe, combined with the fact that there is an alternative to employing more assistants: self-help.

There is a trade-off in shopping. Customers can choose to go to shops with lots of assistants, which are usually more expensive because their costs are higher. Or they can go to cheaper shops where they are likely to spend more time finding what they want themselves and then spend even longer waiting to pay. In Europe, because the costs of employing shop assistants are higher than in the United States, shops manage to keep their costs down by shifting part of the assistant’s job to the customer. IKEA, the home products retailer, could not have been born in the United States.

Something similar is happening in business services. American companies are using external advisers and specialist services much more frequently than European companies, because it is cheaper and quicker to set up and operate such businesses in the United States. Instead, European companies might go without some services or they might provide them internally.

The advantage of external services is not only in employment but also in efficiency. By specialising in business services, independent providers are able to improve efficiency and provide a better service for other companies. So Europe is not only losing out in employment by not making it easier to set up and operate business services, we are also losing in productivity.

But the biggest growth in the gap between the United States and the eurozone is also the most controversial. Employment in health has grown much faster in the United States than in Europe, even though the European population is ageing faster than the American one. Why is that?

The jobs in the American health sector are not only in medical services but also in care, for both young children and older people. But the cost of these services has also risen enormously. Is the reason that we are not creating enough jobs in healthcare services in Europe the fact that we are not allowing costs to rise faster? I would like to think that this is not the reason.

In Europe, we have a more caring social system supported by public policy, and much of the cost of education and healthcare is borne by the state. Demand for these services, especially for health, will increase in the future, partly because of our ageing populations, but also because with rising living standards we expect better personal services and better healthcare.

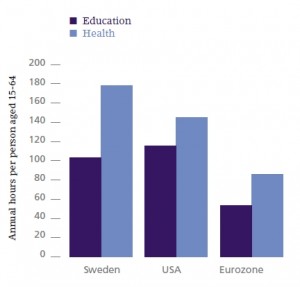

How can our governments meet the costs of these services? The United States has shown one way: by allowing costs to increase and letting the private sector take the initiative. Sweden and the other Scandinavian countries have shown another way: by increasing taxes and using the revenue to subsidise jobs in healthcare.

The hours of work devoted to jobs in health in Sweden exceed even those in the United States, while hours worked in the eurozone fall well short of both (see Figure 2). But the taxes needed to finance these jobs in Sweden are very high compared with those in other European countries. Job creation in other sectors, such as retailing and home repairs, has suffered, which means that overall Sweden is behind the United States. So even within Europe, it is not a coincidence that IKEA is a Swedish company. It is also not a coincidence that eating out in Sweden is much more expensive than – and probably not as common an occurrence as – eating out in, say, Italy.

Figure 2: Annual hours per person aged 15-64

Is this the future of work in Europe? Will our taxes have to go up to subsidise jobs in the sector that will surely feel most pressure for job creation? European citizens have a tough decision to make. But before they even have the luxury of addressing that issue, they must sort out their debt problems. Otherwise the social care system that is so deeply rooted in Europe’s culture will become untenable.

This article summarises his lecture at the Fourth Lindau Meeting on Economic Sciences in August 2011, an event that brought together 17 of the 38 living economics laureates with nearly 400 top young economists from around the world.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2011 edition of the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance Magazine, CentrePiece.