In the two decades since its break up, the countries of the former Soviet Union have undergone significant economic growth and development. But current health outcomes in these countries do not reflect this, and this can have significant side effects on other aspects of society, such as the workforce. Yevgeniy Goryakin and colleagues find that the poor health of people in these countries can lead to people having a 13-15 per cent higher probability of not working.

In the two decades since its break up, the countries of the former Soviet Union have undergone significant economic growth and development. But current health outcomes in these countries do not reflect this, and this can have significant side effects on other aspects of society, such as the workforce. Yevgeniy Goryakin and colleagues find that the poor health of people in these countries can lead to people having a 13-15 per cent higher probability of not working.

It is well recognized that the health of adults (especially males) living in the countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU) is much poorer than could be expected given their level of economic development, but what impact does this poorer health have on these country’s labour supply? Examining the effect of ill health on labour supply in nine countries of the former Soviet Union, we found that self-reported poor health is associated with about a 13-15 per cent lower probability of working.

Poorer health in the countries of the former Soviet Union

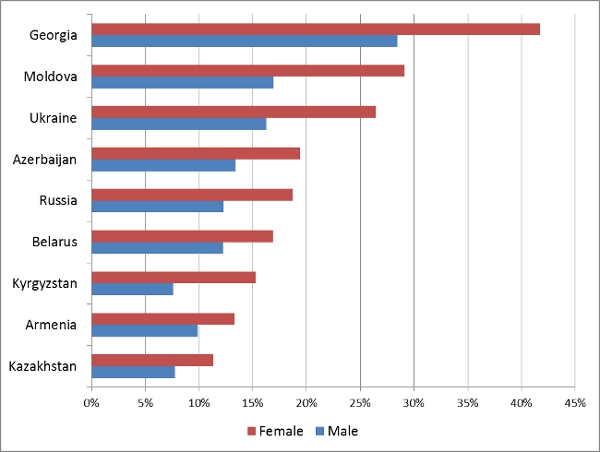

Male life expectancy in Russia is about 64 years (112th place among 193 countries, according to 2006 UN World Population Prospectus), while its GDP per capita, in purchasing power parity terms, is US$16,736 (putting it in 53rd place, according to the IMF). For Russian males in 2000-2001, the probability of dying between the ages of 15 and 60 was about 42 per cent. In comparison, this was about 10 per cent in Japan, 14 per cent in the US, 13 per cent in Germany, and 22 per cent in Turkey. Interestingly, although objective indicators suggest that the health of males living in the FSU is worse than that of females (for example, women on average live 12 years longer than men in Russia); in surveys women tend to self-rate their health worse than men, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Proportion of people who report their health to be poor or very poor, by country and gender

Source: Health in Times of Transition dataset, 2010.

The legacy of poor health is seen even in the more successful FSU countries that have joined the European Union. For example, overall life expectancy in Estonia is about 71.4 years (104 ranking in the world), even though the country occupies 43rd place in the world in terms of its GDP per capita adjusted for Purchasing Power (according to the IMF).

The existing theoretical and empirical literature demonstrates that the impact of health on labour supply is by no means straightforward, so it must be determined empirically in different settings. Theoretically, while poor health is expected to decrease productivity and wages, the effect of health on labour force participation is not so clear. Thus, the resulting lower wages may affect the marginal rate of substitution between work and leisure (so that individuals may choose leisure over work), or it may act through an income effect to increase demand for work. These mechanisms will affect the supply of labour in opposite directions.

We have examined the effect of ill health on labour supply among those over 18 years of age living in nine countries of the former Soviet Union (Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan). The richness of the dataset allowed us to employ a more advanced empirical strategy than that used in the earlier literature in this region, in that we aimed to estimate the causal effect of ill health on labour supply in these countries.

We found that self-reporting poor health is associated with about a 13-15 per cent lower probability of working in the countries studied. We found that constantly having to limit consumption of basic food and medical care in the last 12 months increases the probability of reporting poor health by about 8 per cent and 11 per cent respectively.

The significant reduction in labour supply in response to poor health that we found may have welfare implications both for employees and their families, through a reduction in their earned income and therefore increased risk of poverty, and to their employers, especially if the employees are salaried and accumulate sick leave. In addition, available evidence suggests that in Russia (and likely in most other former Soviet countries), disease severity is likely to be significantly related to out of pocket medical expenditures, even in the presence of medical insurance. The deleterious economic consequences of disease may thus go beyond labour-related losses incurred by a sick individual. The upside is that the economic costs of ill health can also be seen as an additional benefit that can be expected from public health interventions in these countries. This benefit needs to be factored into any calculation of the true costs and benefits of interventions designed to address the serious adult health problems in the region.

This article is based on: Goryakin Y, Rocco L, Suhrcke M, Roberts B, McKee M. The effect of health on labor supply in nine Former Soviet Union countries. Presented at 2012 Conference on Health Economics. The paper uses the data from household surveys undertaken in nine countries of the FSU in 2010 as part of the Health in Times of Transition (HITT) study.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/QKzdnF

_________________________________

Yevgeniy Goryakin – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Yevgeniy Goryakin – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Yevgeniy Goryakin is at the Department of Health Services Research and Policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. His research interests include, social capital and health, the labour market consequences of poor health, obesity and socio-economic status, and the social determinants of nutrition behaviour.