Since 2000, Vladimir Putin has spent two terms as Russia’s President and one as Prime Minister. Now that he has regained the presidency, many commentators are concerned that the Russian public has become more accepting of his increasingly autocratic government. Ellen Carnaghan argues that in societies undergoing political change like Russia, the concept of ‘democracy’ may vary widely from accepted norms, and using survey data, finds that the Russian public’s support for democracy may be greater than previously thought.

Since 2000, Vladimir Putin has spent two terms as Russia’s President and one as Prime Minister. Now that he has regained the presidency, many commentators are concerned that the Russian public has become more accepting of his increasingly autocratic government. Ellen Carnaghan argues that in societies undergoing political change like Russia, the concept of ‘democracy’ may vary widely from accepted norms, and using survey data, finds that the Russian public’s support for democracy may be greater than previously thought.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s high levels of popular support have sometimes been interpreted as public acceptance of the moves toward greater autocracy that occurred during his first two terms as president and continued when he served as prime minister. While the results of some Russian public opinion surveys seem to confirm that impression, survey results may give an impression of less support for democracy than actually exists. Measuring support for democracy in societies where democratic institutions are not present or do not function well is a challenge. In societies moving either toward or away from democracy, the very meaning of “democracy” is often in question and institutions and practices that go by the label of “democratic” often vary widely from accepted norms. Interpreted in this light, survey results provide evidence of perhaps more passive support for democracy among ordinary Russians than is generally imagined.

Putin started his third term as president of Russia in the face of significant popular opposition. Does this emergent opposition indicate a wide-spread popular defense of democracy in the face of Putin’s increasingly autocratic tendencies? Or is the opposition just a small group at odds with dominant trends in popular political orientations?

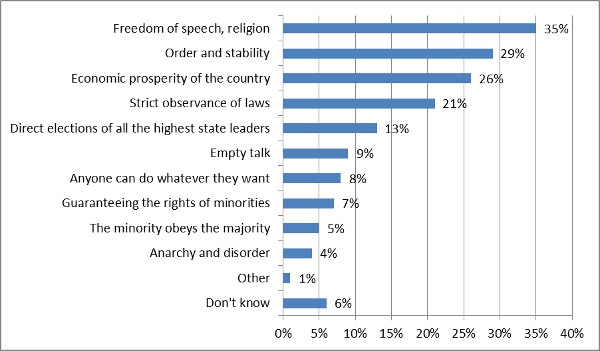

According to polls conducted in Russia by the Levada Center, only about 20 per cent of respondents think Russia needs the kind of democracy found in Europe and America, and that percentage seems to be declining over time. Russians are more likely to think that what is happening in Russia is the development of democracy than that it is the approach of dictatorship. They are more satisfied than not with the fairness of Russian elections. As Figure 1 illustrates, they tend to favour “order” and a ruler with a “strong hand.” Public opinion surveys also indicate little popular interest in opposition politics.

Figure 1: What do you think is most important to be able to speak about democracy in this country?

Source: Levada Center nationwide survey, 17-21 December 2010, N=1611 www.russiavotes.org

But survey results may give an impression of less support for democracy than actually exists. Measuring support for democracy in societies where democratic institutions do not exist or do not function very well is a challenge. Even in stable societies where citizens have considerable experience with democracy, survey respondents may not completely understand the meaning of the questions that they are asked, and researchers may not accurately interpret the meaning of the answers that they receive. In societies moving either toward or away from democracy, the very meaning of “democracy” is often in question and institutions and practices that go by the label of “democratic” often vary widely from accepted norms. Having learned about their political institutions since they were schoolchildren, citizens of stable political systems are equipped with a set of words and concepts that they can use to understand and to talk about their government. In societies undergoing political change, citizens do not have that advantage. As a result, respondents are likely to interpret survey questions on democratic concepts in unpredictable ways, and their answers may mis-communicate the intended meaning. This tendency toward miscommunication is an inherent by-product of the difficulty of talking about democracy in contexts where it does not fully exist.

This problem is particularly profound for questions containing the word “democracy.” As part of two different research projects, I conducted a series of systematic, intensive interviews with ordinary Russians between 1998 and 2011. The answers that people provided in these interviews illustrate the variation of meaning that might be attached to the word “democracy.” Some people described what democracy had meant in their own experiences: leaders who evaded their responsibilities to the nation; closed factories and economic hardship. Others talked about democracy in terms of single pieces of a complex system – personal freedom, elections, or the observance of law. As a result, when Russians answer survey questions about the need for Western style democracy in Russia, it is hard to know what they have in mind.

Survey researchers are of course aware of this problem and try to avoid it to the degree that they can. One strategy is to avoid using the word “democracy,” asking instead about various aspects of democratic systems, usually elections, institutions, and individual liberty. My respondents show that even these less abstract questions rely on words that mean different things to different respondents. Survey questions sometimes ask about particular institutions – presidents, parliaments, elections, courts – that are the vehicles for the participation, competition, or the protection of individual rights that are at the heart of democracy. But this strategy depends on respondents recognising the significance of specific institutions, and it is not clear that ordinary citizens can always do this, or that the differences they see are the same as the ones survey researchers have in mind. Another problem with questions about particular institutions is that respondents may answer in terms of the specific – and often flawed – institutions of their own experience instead of in terms of how those institutions are supposed to work in the abstract world of perfect democracy.

Survey researchers use phrases like “a strong hand” or “strict order” as code words indicating authoritarian rule and limits on personal freedom, but it is not clear all respondents successfully crack the code. My respondents, for instance, were in favor of “strict order,” but they understood that to mean that everyone – including government officials – would be bound to obey the law. For many of my respondents, order was not the opposite of democracy or any practical concept of freedom. Rather, order – along with democracy – occupied a midpoint between autocracy on the one hand, and chaos, random violence, and social collapse on the other. As one young man explained, “order supports the majority of spheres. But nothing will come of anarchy, which is what you get without order.”

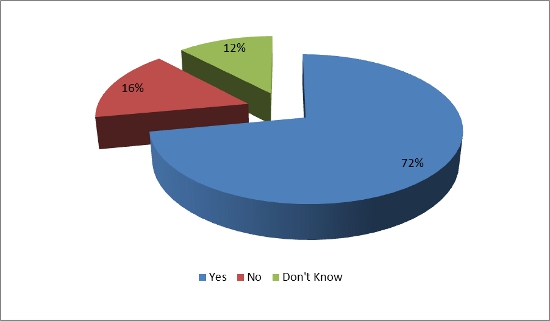

The upshot of all this is that survey responses probably underestimate the degree to which ordinary Russians favour democracy. In addition, there is much in Russian survey responses that indicates considerable support for many aspects of democracy. Although ordinary Russian citizens can be somewhat hazy about the expected organisation of democratic institutions, they are much more consistent in their support for individual rights. This feeling may be most intense in regard to personal liberties – like the right to travel freely – but it also extends to political rights. Generally, citizens do not think the interests of the state take precedence over the rights of individuals. As Figure 2 shows, a large majority of citizens think opposition groups should exist, and they do not support the use of force against such groups, even though they do not personally expect to find themselves at a protest rally.

Figure 2: Do you think Russia needs social movements and parties that are in opposition to the President and government and can exert an important influence on the life of the country?

Source: Levada Center nationwide survey, 18-22 December 2009, www.russiavotes.org

In sum, there are many people who support the basic tenets of democracy among ordinary Russian citizens. The emerging Russian opposition is not without a potential base of popular support.

This article is a shortened version of the Russian Analytical Digest paper, ‘Popular Support for Democracy and Autocracy in Russia’.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/Xea60u

_________________________________

Ellen Carnaghan – St Louis University

Ellen Carnaghan – St Louis University

Ellen Carnaghan is Professor and Chair of the Political Science Department at St Louis University in St Louis, Missouri, USA. She has published articles on popular attitudes in Russia and Eastern Europe in Comparative Politics, Democratization, Post-Soviet Affairs, P.S: Political Science and Politics, and Slavic Review. Her recent book, Out of Order: Russian Political Values in an Imperfect World (Penn State University Press, 2007) examines how the political values of Russian citizens have been shaped by the disorderly conditions that followed the collapse of communism.