A common assumption is that the largest EU countries get their way most often in negotiations within the EU’s institutions. Contrary to this perspective, Jonathan Golub finds that smaller states like Finland tend to be far more successful at negotiating EU legislation than countries like France and Germany. He also finds little evidence for the idea that Member States might ‘buy influence’ by trading legislative outcomes for contributions to the EU budget. Indeed, the same countries which are successful at negotiating legislation are also likely to pay less than their fair share into the budget.

A common assumption is that the largest EU countries get their way most often in negotiations within the EU’s institutions. Contrary to this perspective, Jonathan Golub finds that smaller states like Finland tend to be far more successful at negotiating EU legislation than countries like France and Germany. He also finds little evidence for the idea that Member States might ‘buy influence’ by trading legislative outcomes for contributions to the EU budget. Indeed, the same countries which are successful at negotiating legislation are also likely to pay less than their fair share into the budget.

Criticism of the European Union comes in many flavours. Some Eurosceptics fear that Germany dominates, shaping integration to suit its own interests. Others worry that the EU tilts too much in favour of France. Or perhaps the “Franco-German axis” jointly calls the shots. Recriminations over which states get what pervade EMU negotiations as well as EU budget talks: those yearly festivals of national outrage where leaders insist – some more diplomatically than others – that their country contributes too much and receives little of value in return. But to get a full picture of how the EU works, and of which national views tend to prevail, attention must focus on the EU’s main activity: adopting legislation. Hundreds of policies every year, governing everything from products and services to food and the environment, agriculture, fishing, banking, working conditions; the scope of EU law is enormous and growing.

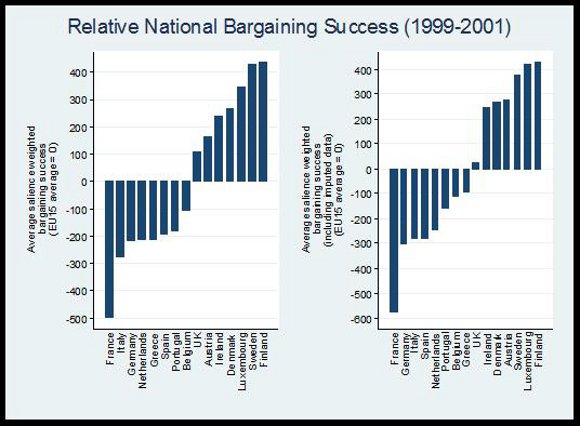

Like previous studies of legislative bargaining success, I analysed data from the European Union Decides project, an international collaboration that tracked 162 policy issues negotiated between 1995 and 2002. Most of the laws were adopted between 1999 and 2001. For each proposal, the project identified and placed on a scale from zero to one hundred every country’s ideal policy position, the importance (“salience”) they attached to the proposal, and the position of the agreed outcome. In cases where national positions were not recorded, some authors have decided to impute these missing values, others to omit them, so I considered both approaches.

How do we determine which states achieve the most when hammering out the details of EU legislation? Because salience levels vary sharply, the most successful states are not simply the ones whose preferred positions match the adopted laws. Even a small concession on a highly salient policy can have serious negative domestic consequences. Conversely, carrying the day on a policy with trivial domestic consequences isn’t much to brag about. I therefore examined each country’s salience-weighted bargaining success: the distance of its ideal position from the outcome, multiplied by the salience, aggregated across the 162 issues.

The results will prove reassuring to some, alarming to others. Figure 1 compares each country’s average bargaining success to the average success of all fifteen Member States. The left panel excludes missing values, the right includes imputed data. Either way, there is absolutely no sign of French or German dominance. In fact, their bargaining success is far below average. My statistical analysis shows that many of the smaller states including Finland, Sweden, Luxembourg, Denmark, Ireland and Austria tended to enjoy significantly more bargaining success than either France or Germany or Italy. Even in the fields where one might have expected them to excel — France in agricultural policy, Germany in internal market policies — neither beat the smaller states. Of the large states, only the UK’s bargaining success matched these much smaller overachievers.

Figure 1: Average Salience Weighted Bargaining Success (1999-2001)

Why small states achieve such relative success is not entirely clear. It helps that they concentrate their efforts on a limited number of proposals and avoid taking extreme positions that leave them marginalised. But even after we control for these factors, French and German performance lags considerably.

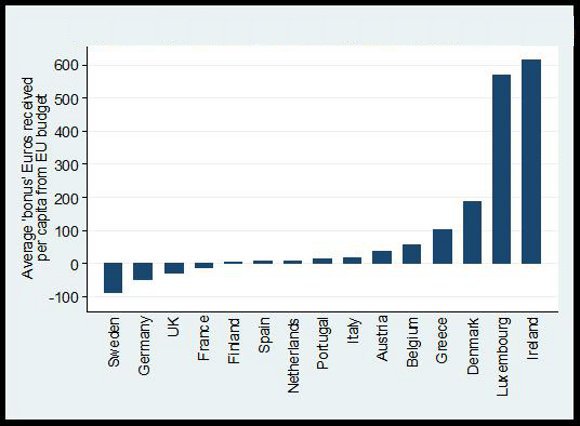

Perhaps legislative winners pay for their bargaining success with budgetary contributions? Previous studies have calculated what a fair distribution of net national contributions would look like, based on the principle that net contributions should be proportional to national GDP per capita. Any amount a state receives from the EU budget beyond their fair share I treated as a “bonus”. I expected that EU budgetary data for the 1995-2002 period would show an inverse relationship between national bonuses and legislative bargaining success, and also that knowing which states contributed the most money would improve our ability to predict policy outcomes. Legislative winners can afford to be financially generous, since “the policies we want” is a powerful answer to the question “what do we get for all that money we contribute to the EU budget?” For states with below average bargaining success, sizeable financial transfers can serve as a welcome compensation. States that care more about the money than about the policies might even be willing to sell their votes in the Council of Ministers.

Figure 2 illustrates that, remarkably, most bargaining winners are not budgetary losers: they win on both counts. Only Sweden has a high level of legislative bargaining success while contributing relatively more than any other state to the EU budget. Finland didn’t even pay its fair share. Ireland, Luxembourg and Denmark received enormously favourable treatment from the EU budget. Germany and France, two of the states with the worst relative bargaining success, are also two of the biggest budgetary losers. Germany paid 4 billion euros per year more than its fair share. France paid 664 million euros per year more than its fair share. They might wonder what they got for their money. Judging from the position of legislative outcomes, it certainly wasn’t policy influence.

Figure 2: EU Budget Winners and Losers (1995-2002)

Staunch Europhiles might call these types of national comparisons misguided or beside the point. There are, after all, many reasons for countries to support European integration regardless of their relative bargaining success or relative budgetary contribution. That is certainly true, and they may prove sufficient to sustain the EU. But for many citizens, the transfer of political sovereignty to the EU is an easier pill to swallow if it produces either legislation that matches their own state’s national preferences, or a substantial financial bonus. It is hard to be sanguine about Europe’s future if some states foot the bill for the system and dont get the laws they want, while others come out ahead on both policy and money.

We do not yet know whether the patterns I identified for the 1995-2002 period are any different today. Data for the post-2004 era have only just recently become available, so that researchers can now investigate whether in the enlarged EU we see the same constellation of relative national winners and losers.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/WoU2Dd

_________________________________

Jonathan Golub – University of Reading

Jonathan Golub – University of Reading

Jonathan Golub is Reader in Political Science at the University of Reading. His main areas of interest include European Union institutions and policymaking, international political economy, environmental politics, research methods, and judicial politics.

Possibly, along the lines of that claimed by Peter Bursens using the case study of Denmark (Bursens, P., 2002. Why Denmark and Belgium have different implementation records: On transposition laggards and leaders in the EU. Scandinavian Political Studies, 25(2), pp.173–195.), smaller countries can often feel the stronger need from all domestic actors to work together to get one clear mandate for negotiation, and they often have Europe-leading policy designs in some areas such as labour or environmental policy (benefitting from their manageable size), which can be uploaded (and they also can serve as smaller pilot schemes’). This is not always the case in all small countries, but it may explain some successes.