The success of Beppe Grillo’s ‘5 Stars Movement’ in Italy’s elections on the 24-25 February has been regarded by some commentators as a rejection of austerity by the Italian electorate. Marco Simoni argues that rather than rejecting austerity, Italian voters were primarily protesting against decades of economic stagnation, and a political system which is prone to corruption and clientelism. He concludes that unless mainstream politics can reorganise around a credible reform agenda, populist movements will continue to play a key role in the country.

The success of Beppe Grillo’s ‘5 Stars Movement’ in Italy’s elections on the 24-25 February has been regarded by some commentators as a rejection of austerity by the Italian electorate. Marco Simoni argues that rather than rejecting austerity, Italian voters were primarily protesting against decades of economic stagnation, and a political system which is prone to corruption and clientelism. He concludes that unless mainstream politics can reorganise around a credible reform agenda, populist movements will continue to play a key role in the country.

On the 24th of February, Paul Krugman suggested in the New York Times that the surge of the populist “5 Stars Movement” in Italy, and ensuing political instability, was to be blamed on German-led austerity measures.

I am – generally speaking – all in favour of a less dogmatic approach to budget balancing in Europe and, more importantly, to the beginning of a genuine EU-wide fiscal policy capable of correcting market imbalances. That is, in Krugman-speak, my sympathies are more ‘salt-water’ than ‘fresh-water’. However, with regard to Italy, Krugman’s diagnosis does not seem to hold any water. Italians were not holding a referendum on austerity, they were instead voting on the decline of their economy and the ineffectiveness of their – expensive – political classes more broadly.

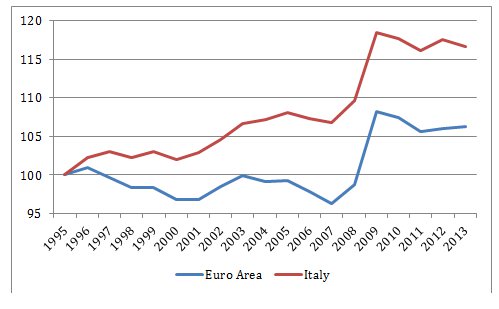

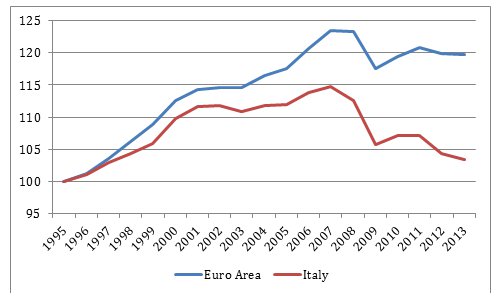

In the figures below I plot public expenditure growth and real GDP per capita growth. While Italy’s expenditure has increased above the Eurozone average since 1995, its rate of economic growth has been far below average. Indeed, it has basically been negligible for over a decade.

Figure 1: Current expenditure as a percentage of GDP (1995=100)

Source: Ameco database

Figure 2: Real GDP per capita (1995=100)

Source: Ameco database

In fact, as Krugman himself underscored in a previous article, the problem with Italy lies in nearly two decades of stagnant growth despite rising expenditure. For those interested, I address the causes behind the decline in this paper. To briefly summarise: erratic economic reforms have failed to provide the economy with the right set of incentives, leading to a stalling of innovation and a decline in productivity.

The political consequences of such a decline were not obvious until the recent elections, when the most unusual electoral law in Western Europe left the country with a hung parliament as a result of fragmented electoral results. Two decades of economic stagnation and incoherent policies have created a very strong insider / outsider dynamic. In Italy, this dynamic cuts across family income and education levels, because rents, market regulations, and diffused monopolies render meritocracy a distant dream. Italians voted for a “party alternative” because of this dynamic, not because of the cost of the more recent austerity measures.

In fact, many de-facto rents and monopolies are strongly intertwined with political agency. During the last twenty years, Italian political parties – at the local and national level – have continued to have strong discretion in the management of public resources, including sizeable direct and indirect financing to party politics. To name a few examples amidst many: public health managers, the board to the large public broadcasting company, and the CEOs and board of directors of local utility companies (all of which are owned by local governments) are de-facto party-politics appointees. This system is unsurprisingly prone to corruption and clientelism, but most importantly is spectacularly inefficient.

What the latest round of elections in Italy represents is therefore a gigantic output-legitimacy crisis (a condition whereby a system loses legitimacy because it proves unable to deliver satisfactory outcomes) of a very expensive system in which the process of political elite formation (the input-legitimacy) is also questioned by a growing share of the population. This translated into extremely fragmented electoral results.

In 2008, 85 per cent of votes went to one of the two main coalitions; today that figure is down to less than 60 per cent. The third political force is now the “5 Stars Movement” (M5S) led by the former comedian Beppe Grillo, which gained 25 per cent of the national vote on the platform of “wiping away” the incumbent party elites. The M5S is a peculiar political party: their leader did not run in the election. Additionally, M5S candidates for the Parliament (as well as their leader) refused to debate their ideas outside their own Internet forum: no M5S candidate was ever broadcasted in TV or Radio within Italy, nor interviewed by the Italian press, which is blamed by the M5S for being part of the system.

Further, the new civic movement led by incumbent Prime Minster Mario Monti won roughly 10 per cent of the vote. Some considered this an unsatisfactory result given the well-regarded reputation of Mr Monti. However, this result is considerable if assessed against the fact that Mr Monti was called in as a non-partisan PM to restore international credibility in the middle of financial turmoil. The decision to run in elections after having implemented tough economic measures, with the aim to consolidate reforms and move towards measures to stimulate growth, remains unprecedented from an international standpoint. At any rate, the future role of the “Scelta Civica” movement will depend on its ability to define a sharp reformist political profile.

The two main parties, the Democratic Party (PD) and the Party of Freedom (PDL) are still very important, but are now obviously tainted by internal political controversy. The former “won” the elections with less than 0.5 per cent more than the right, while shedding 3.5 million votes (or 7 per cent), compared to the 2008 elections (which they lost). The latter lost half of its votes compared to 2008, yet still heads the second largest coalition. Finally, it is worth noting the resilience of the Northern league (Lega Nord), a localist and Eurosceptic movement. Lega Nord is a long-time ally of Berlusconi, but with a remarkable political autonomy. Despite the fact that the party also lost vote share, it now governs the three wealthiest regions of the country.

This fragmentation reflects deep rifts in Italian society, the lack of legitimacy of traditional political leadership and its inability to attract new voters, and the widespread discontent against dismal economic performance. Unless political leadership is reorganised around a credible reformist agenda, populism is likely to continue to increase in importance.

Disclaimer: Marco Simoni serves in the “Scelta Civica” movement led by Mario Monti.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/16m7znH

_________________________________

Marco Simoni – LSE European Institute

Marco Simoni – LSE European Institute

Marco Simoni is a lecturer in European Political Economy at the European Institute of the London School of Economics. His webpage is: personal.lse.ac.uk/simoni.

2 Comments