The principle of ‘intergenerational justice’ implies that young people should be treated fairly in comparison with older citizens. As Craig J. Willy notes, however, large debt burdens, unsustainable economic practices, and the electoral effects of ageing populations present a challenge in ensuring fairness for young Europeans. He argues that while some policies, such as compulsory voting, or providing ‘extra’ votes to parents (Demeny voting), might improve the representation of young people, policy experimentation across Europe is likely to be the key in avoiding a demographic ‘death trap’.

The principle of ‘intergenerational justice’ implies that young people should be treated fairly in comparison with older citizens. As Craig J. Willy notes, however, large debt burdens, unsustainable economic practices, and the electoral effects of ageing populations present a challenge in ensuring fairness for young Europeans. He argues that while some policies, such as compulsory voting, or providing ‘extra’ votes to parents (Demeny voting), might improve the representation of young people, policy experimentation across Europe is likely to be the key in avoiding a demographic ‘death trap’.

A recent study on “Intergenerational Justice in Aging Societies” by the Bertelsmann Foundation’s Sustainable Governance Indicators project shows a number of alarming developments. Today’s young people are saddled with a large debt burden, unsustainable economic practices, relative underinvestment in social programmes, and poverty.

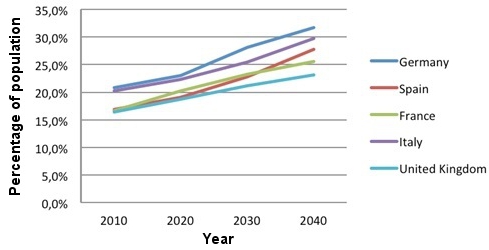

An indicator discussed, but not used, by the study is that of youth unemployment. This has been steadily increasing since the onset of the global economic crisis five years ago and particularly since the onset in earnest of the euro crisis since 2010. According to EU figures, youth unemployment has now reached 23.5 per cent in the European Union, including 7.5 per cent in Germany, 24.7 per cent in the UK, 26.5 per cent in France, 40.5 per cent in Italy, and 56.4 per cent in Spain. There are currently over 5.6 million unemployed Europeans. Even in developed countries this is often a traumatic experience entailing dependence on one’s parents, a failed transition from adolescence to adulthood, and the inability to acquire and maintain lifelong professional skills (a kind of premature hysteresis). Chart 1 below illustrates the problem in the Eurozone and the UK.

Chart 1: Youth (under-25s) unemployment rates in Europe (1990 – 2012)

Note: “J-90” refers to January 1990, “J-92” is January 1992, and so on. Figures from Zero Hedge

In Europe, ‘gerontocracy’ has taken the form of a particular disdain for the problem of youth unemployment. This was especially visible at the latest European summit in which leaders pledged before a skeptical European press €6 billion to create youth jobs. That may seem like a lot, but it makes up less than 0.05 per cent of EU GDP, a sum completely marginal given the scale of the problem. By contrast, President Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package for a comparable-sized economy (which admittedly went beyond youth), was worth $831 billion.

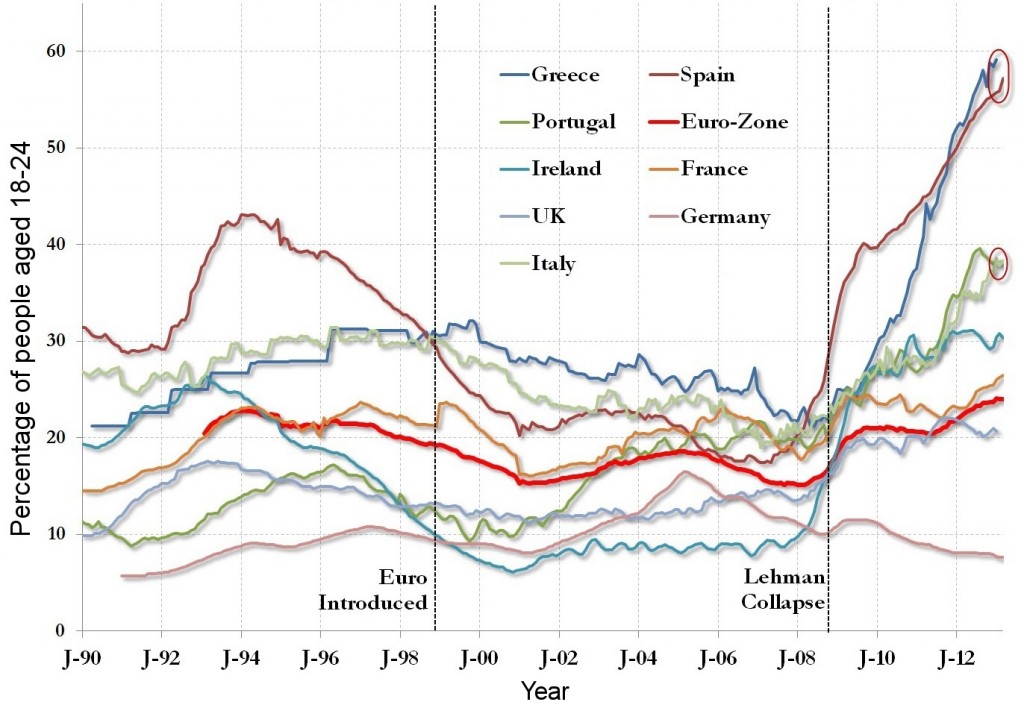

In fact, the problem is likely to prove a lasting one. It is well known that individuals, from adolescence to old age, tend to shift from left to right and from political radicalism to conservatism. We are now seeing this on a vast scale across the developed world, with politics often characterised by extreme timidity and conservatism despite the scale of the economic debacle. The causes of these problems have, in part, been due to the demographic transition. The median age in the EU was 41.5 in 2012 and is projected to rise to 47.6 by 2060. This relatively slow rise masks a far faster change in Europe’s population structure, in particular a very rapid increase in the population (and therefore voting bloc) of over-65s. Chart 2 shows the projected rise in over-65s as a percentage of the overall population of France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom over the next 30 years.

Chart 2: Projected rise in over-65s as a percentage of overall population (2010 – 2040)

Source: Eurostat

In contrast, in most European countries, the size of younger cohorts has collapsed as a result of extremely low fertility. With a few notable exceptions – France, the UK, the Low and Nordic countries – women across Europe are on average having 1.3 children. Evidence suggests couples may be having even less children due to a “baby recession” caused by the crisis. This is on top of the generally low voter turnouts of younger voters (in France in 2012, 19 per cent of under-25s didn’t vote in the presidential elections as against a 13 per cent national average).

Would mandatory and proxy voting increase intergenerational fairness?

The solutions to this are difficult to identify. The Bertelsmann report suggests the controversial idea of Demeny voting, parents getting extra votes on behalf of their children and voting by proxy. The idea has notably been promoted by the ruling Fidesz party in Hungary.

An alternative option is compulsory voting, which in most countries would entail more votes from younger and poorer citizens. Countries with mandatory (more or less enforced) voting in Europe include Belgium, Italy and Greece, all of which have traditionally high levels of voter turnout (>90 per cent). However, this has neither translated into low youth unemployment, nor high marks for intergenerational justice according to the Bertelsmann report. All three have particularly high public debt.

In addition, it isn’t certain whether giving more voting power to younger people would lead to more sustainable policies. Thus in Europe, electorates even in the crisis countries have, broadly speaking, proven relatively conservative and particularly attached to the common currency. Older voters appear terrified at the thought of losing their pensions and savings to a devalued currency. Young people are traditionally more open to European cosmopolitanism and express relatively higher attachment to the euro in polls.

Notwithstanding this, there would be changes. So in Italy, 47.2 per cent of young people voted for Beppe Grillo’s Movimento Cinque Stelle, whose policies (notably debt restructuring and self-financing via the central bank) may in fact improve one major intergenerational justice indicator. In contrast, over two-thirds of French youth voted for moderate center-left, center or center-right parties. Interestingly, people aged 25-59, the most likely to receive Demeny votes, were the most likely to vote for either the far-right Front National (19-23 per cent as against a 17.9 per cent national average) or the far-left Front de Gauche (11-13 per cent as against an 11.1 per cent national average).

Ageing Japan has gone “radical”

In any event, the predominance of the older vote is going to increase massively across Europe in the coming years, with the partial exception of the northwestern Atlantic fringe. There are no hard-and-fast policy solutions. Whatever one’s policy or framework, ultimately a country at any given time consists of the individuals that make up its population. If half the population is over 50 and a third over 65, the consequences will simply have to be managed and no economic or other policy can annul them.

Perhaps then the only “solution” for intergenerational justice in the context of massive ageing is simply the awareness among the elderly that, ultimately, society as a whole (including themselves) will only be as well-off as the young workers who are supporting it.

Japan offers an interesting case of a very aged society (much of Europe will soon resemble it) which remained stuck in the same zero-growth policies for 20 years. Now Japan is experimenting in heterodox “Abenomics” and, whatever its outcome, further radical policy changes appear likely as the society fights against the demographic “death trap.” Perhaps also in Europe, the pressures of ageing will, in time and in themselves and despite the rise of conservatism, force through radical changes of policy at the national and European levels.

No one can say with certainty what policies would fully tackle the challenges of intergenerational fairness. Perhaps then Europe’s greatest asset is its diversity: the more different nations experiment with diverse policies, the higher the chance that one will find policies that will work, which could then be emulated by others.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/16FPUpC

_________________________________

Craig J. Willy

Craig J. Willy

Craig James Willy is a freelance EU affairs writer and blogger. He has notably researched and written political analysis for the Bertelsmann Foundation and media analysis for the European Commission. His French-English blog is available here.

Let us get TWO things straight. First the ageing population (pensions) costs us NOTHING. it is all paid out of CREATED MONEY by computer entries, which are used over & over again.

Second there is no DEBT, or Deficit ,that can be handed down to our children. Both of these scare stories are BOGUS. They are designed to divide the people.

While we are at it lets dispel the other Myth, that TAXES pay for Government spending. They do not pay for anything. Not one single PENNY of taxpayers money is spent by Gov’t. TAXES are used to regulate the economy by taking the heat out of Internal inflation, if it should be a problem. This is not our problem NOW.

Our problem NOW is that the people are OVER-TAXED so there is not enough money going into the economy. Why are they Over-taxed??? because of the stupidity of the MYTH that taxes have to equal Gov’t spending. What about the £2.9 TRILLIONs that the Banks created for home mortgages? http://www.positivemoney.org/issues/democracy