The European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) was launched in May 2012 with the aim of allowing EU citizens to participate more effectively in EU decision-making. Individuals can request that the European Commission proposes an item of legislation at the European level, provided that the initiative is backed by at least one million citizens. Luis Bouza Garcia argues that while very few campaigns are capable of attracting one million supporters, the ECI has wider value in encouraging actors from civil society to engage with the public, rather than simply attempting to lobby the EU’s institutions directly.

The European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) was launched in May 2012 with the aim of allowing EU citizens to participate more effectively in EU decision-making. Individuals can request that the European Commission proposes an item of legislation at the European level, provided that the initiative is backed by at least one million citizens. Luis Bouza Garcia argues that while very few campaigns are capable of attracting one million supporters, the ECI has wider value in encouraging actors from civil society to engage with the public, rather than simply attempting to lobby the EU’s institutions directly.

The debate over the EU’s democratic deficit has lasted for more than two decades, and the Eurozone crisis proves that the issue is far from being resolved, notwithstanding the reforms carried out to improve the EU’s legitimacy. These have included extending the powers of the European Parliament, involving national parliaments in the control of subsidiarity, adopting transparency legislation, and developing mechanisms for citizens and organised civil society participation in policy-making.

Encouraging participation was an important element of the institutional reform agenda at the turn of the century. In particular, the period between 2001 and 2005 saw a number of proposals in relation to participation – the 2001 White Paper on Governance being the best known one – which culminated in a Treaty article (art. 47) on participatory democracy in the proposed European Constitution. Despite a somewhat diminished framing – including the suppression of the term ‘participatory democracy’ in the heading of the Treaty article – the content of article 47 was maintained untouched in the new Lisbon Treaty article 11 (TEU).

This Treaty article is to a large extent the result of two different lobbying campaigns during the Convention on the future of Europe in 2002 and 2003. Following regular involvement in the Convention, some of the larger Brussels-based civil society organisations obtained the recognition of civil society dialogue with EU institutions. An entirely different campaign succeeded at obtaining support for an amendment granting one million European citizens the right to ask the Commission to propose legislation within the remit of its powers and the limits of the treaty.

This provision has come to be known as the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI). It has received praise as a novel development in direct democracy beyond the nation state, but it has also been criticised as a weak device which is incapable of influencing the agenda of EU institutions. Unlike the Californian or Swiss referendum initiatives, which allow citizens to trigger a referendum on their demands, the ECI is better classified as an agenda setting initiative: signatories express a formal demand, but representative institutions retain full control over whether and how to turn it into policy.

Hence the ECI leaves the Commission’s monopoly of legislative initiative untouched by making this institution the gatekeeper of demands. Furthermore, comparative experience suggests that political elites tend to ignore initiatives that are not supported by a credible referendum challenge. The experience of Spain, where only one of 66 agenda initiatives has been turned into law, is indicative of this tendency.

Is the ECI therefore an example of ‘much ado about nothing’, where aspirations to democratise the EU have inflated the importance of a weak device? Even if this seems the logical conclusion from the weakness of the new mechanism, it ignores its potential effect in the field of EU interest representation. The main effect of the ECI may not be the passing of large amounts of new legislation, but rather the enlargement of the Brussels policy-making community to new constituencies, and the inclusion of more politicised demands in the agendas of the EU’s institutions.

The aforementioned dialogue between EU institutions and civil society has tended to create a constituency of EU level organisations specialising in policy advocacy, but relatively disconnected from grassroots activism. Citizens’ interest organisations have established themselves in Brussels for almost two decades now, and contribute to making EU policy-making more plural in fields such as the environment, social policy and development policy. They have developed professional lobbying skills and acquired a role in policy-making in some areas, creating opportunities for divergent interests to check each other.

The contribution of civil society organisations to a more pluralistic policy-making notwithstanding, these organisations have hardly met expectations that they would enlarge the European public sphere and contribute to bringing the EU “closer” to citizens. Brussels based organisations have incentives to concentrate their efforts in policy advocacy through lobbying in order to influence legislation, but they have little incentive to engage in mobilisation campaigns among grassroots citizens. However signature collection tools such as the ECI belong to a form of collective action requiring the ability of mobilising citizens in support of a cause. Causes promoted via the ECI will thus mobilise a different constituency of organisations and social movements.

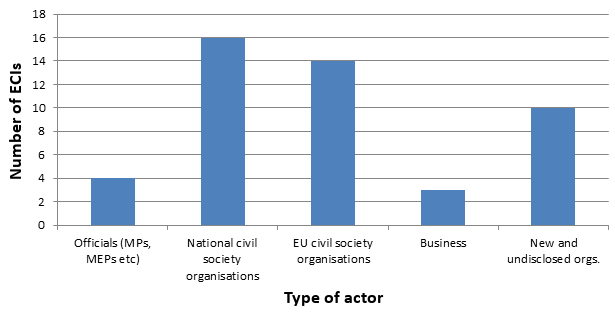

Analysis of the signature collection campaigns undertaken supports this hypothesis. The Chart below shows that the ECI does already attract a more varied constituency, as it is already attracting more national rather than European organisation. It is also attracting a number of grassroots initiatives coming from new groups.

Chart: Types of actor responsible for launching European Citizens’ Initiatives

Note: The chart shows the number of signature collection campaigns launched before the formal opening of the ECI (2003-2012) according to Kaufmann data and those introduced from 2012 onwards.

This does not automatically bring EU policy-making closer to citizens. The ECI remains a minority tool as one million signatures represents 0.2 per cent of the population of the EU, and the typical strategy of signature collection does not aim at fostering debate in the public sphere, but at mobilising those already convinced. However the very fact that organisations using bottom-up mobilisation may get involved in EU politics is likely to change the way in which the EU agenda is established and the incentives of actors. Organisations will perceive that there is a potential reward – the introduction of subjects in the institutional agenda – in the mobilisation of citizens and may thus diversify their usage of advocacy tools.

Furthermore, civil society will be less reactive to Commission proposals and will be able to introduce new issues to the agenda. This can potentially contribute to making EU politics more controversial in comparison with the traditional preference for consensus on issues of low politics. A good example of that is found among on-going initiatives.

One lesson from the first year of using the tool is that very few organisations are capable of collecting one million signatures. Only two campaigns have achieved this so far. The first of them – the exclusion of water provision and sanitation from internal market rules and from liberalisation – also proves that the ECI provides an incentive for established organisations to engage with the public sphere. In this case, some of the larger Brussels civil society organisations have co-operated with national organisations to achieve two million signatures.

The second campaign close to one million signatures – asking for a ban on EU funding for research with embryos – is an example of how civil society groups (in this case pro-life organisations) may use the device to Europeanise social cleavages. This type of initiative is traditionally the kind of issue that EU institutions try to avoid. Ultimately if the ECI can bring more controversial issues to Brussels it may eventually contribute to making the public more interested in EU policy-making.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics or the author’s institution.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1dfe2DO

_________________________________

Luis Bouza García – College of Europe

Luis Bouza García – College of Europe

Luis Bouza García is the Academic Coordinator of European General Studies courses at the College of Europe in Bruges.

2 Comments