The issue of arms exports has caused significant controversy in a number of European countries. Jennifer L. Erickson looks at EU arms transfers and the human rights status of arms recipients between 1990 and 2010, finding that there is often a disconnect between arms trade policy and practice. She argues that in cases where EU foreign policy relies on member state implementation, existing national priorities or individual material interests may prevail over EU norms. This has the potential to undermine the normative power of the European Union.

The issue of arms exports has caused significant controversy in a number of European countries. Jennifer L. Erickson looks at EU arms transfers and the human rights status of arms recipients between 1990 and 2010, finding that there is often a disconnect between arms trade policy and practice. She argues that in cases where EU foreign policy relies on member state implementation, existing national priorities or individual material interests may prevail over EU norms. This has the potential to undermine the normative power of the European Union.

The issue of arms exports is a continued source of controversy in the EU. In recent years, the EU and its members have been strong supporters of multilateral humanitarian arms export initiatives, including the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports (now a Common Position) and the UN Arms Trade Treaty. However, arms sales still generate intense debates over how best to implement EU arms trade norms, while at the same time protecting valuable export markets.

The outcome of these debates has important consequences for the development of global humanitarian arms trade standards, as well as the credibility of the Union’s “normative power.” Arms export licensing competence rests with member states. As a result, the EU must depend on its members to translate EU principles into practice. However, in cases where normative power and material interests collide, normative power may struggle to influence member state behaviour.

Assessing EU normative power

The promotion of EU values related to peace, human rights, and democracy has long been at the heart of EU external policy. But understanding to what extent the EU is a normative power is a challenging task. By analysing policies alone, we risk confirming a view of the EU as it wants to be seen, but may or may not actually be.

Although EU members broadly agree on their collective values, it should not be surprising to find a gap between EU policy and practice. As with any foreign policy actor, actions may not always live up to words. Beyond this, the EU is a highly complex institution composed of diverse states and often depends on consensus among those states to act. Members may also implement, interpret, or ignore EU foreign policy decisions according to their own national interests. As a result, the consistency and strength of EU normative power may be constrained by member state interests.

European arms transfers

EU member states account for approximately 34 per cent of major conventional arms transfers worldwide. During the Cold War, European arms producers were known for “sell to anyone” policies, seeking to protect production lines and employment. After the end of the Cold War, shrinking domestic defense budgets intensified pressures to export in an increasingly competitive global marketplace saturated with cheap weapons from the former Eastern Bloc.

Nevertheless, EU members began to lay out shared arms export standards in the early 1990s. This effort was partly prompted by damaging revelations that some governments had secretly armed Iraq during its war with Iran. In 1998, the EU passed a formal Code of Conduct outlining eight criteria for export licensing, which include respect for human rights and the preservation of peace. Since the early 2000s, EU member states have also been strong supporters of humanitarian arms export initiatives at the international level. All 28 members have signed the 2013 UN Arms Trade Treaty prohibiting small and major conventional arms transfers that risk being used in conflicts or human rights violations.

EU arms exports and human rights

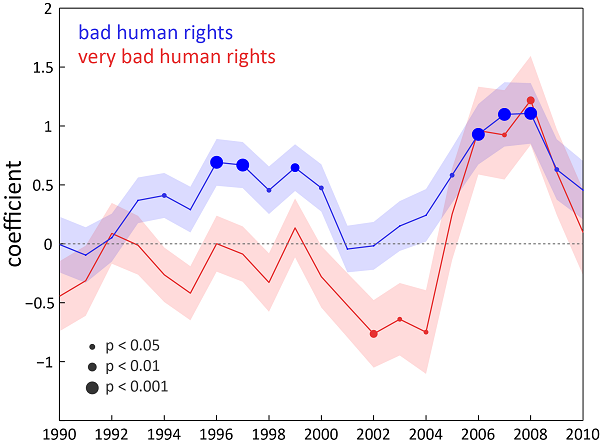

On paper, EU arms export policy is fully consistent with EU normative power. The reality, however, is more complex. Figure 1 shows that small arms and light weapons, which are commonly used tools of internal conflict and repression, were indeed transferred to the best human rights performers more often than to the worst human rights performers for a brief period in the early 2000s. More recently, however, ‘bad’ and ‘very bad’ human rights performers receive small arms more often. That is, as human rights worsen, arms transfers are more frequent.

Figure 1: EU small arms transfers and human rights (1990-2010)

Note: Dichotomous small arms variable coded from NISAT records. The solid lines show the estimated frequency with which EU small arms transfers took place between nine top EU exporters and countries that have ‘very bad’ and ‘bad’ human rights scores on the Political Terror Scale relative to the very best human rights performers. The shaded areas around each line indicate one standard deviation from the coefficient, while the dots show significance (p) values. A value above 0 on the vertical axis roughly indicates that ‘very bad’ and ‘bad’ rated countries were more likely to receive EU small arms transfers but are not statistically significant except where indicated. Additional independent variables include GDP per capita; polity2; internal conflict; oil production; year dummies.

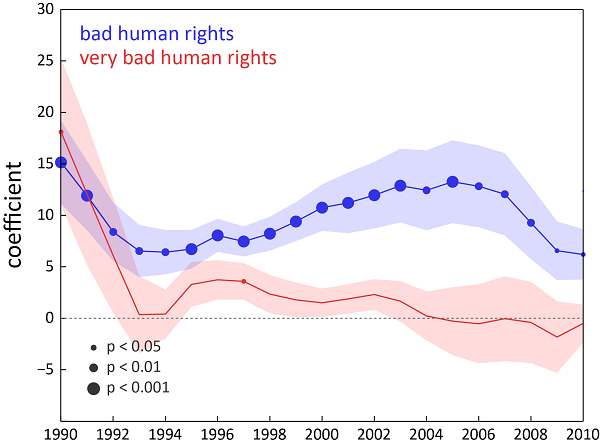

In the case of major conventional arms transfers, which are seen as lucrative weapons with more symbolic foreign policy power, ‘bad’ human rights performers are consistently rewarded with more weapons than the best human rights performers, as shown in Figure 2. ‘Very bad’ human rights performers are neither punished nor rewarded significantly.

Figure 2: EU major conventional arms transfers and human rights (1990-2010)

Note: Continuous major conventional weapons data from SIPRI. The solid lines show the estimated amounts of EU major conventional weapons transfers measured in SIPRI “trend indicator values” to countries that have ‘very bad’ and ‘bad’ human rights scores.

The China arms embargo debate

The 2003-2005 debate over lifting the EU arms embargo to China put differences in members’ approaches to arms transfers and human rights promotion on prominent display. Some members, mainly in Scandinavia, opposed lifting the embargo without tangible improvements in China’s human rights record. The UK and some Eastern European members opposed lifting it without US approval. Other member states argued that the embargo had outgrown its purpose of punishing China after the events of Tiananmen Square and hindered commercial opportunities.

France, Italy, and Germany in particular have interpreted the arms embargo to China to enable arms transfers to China and have sought to use its lifting as a means to deepen economic ties. After China passed its Anti-Secession Law in March 2005, momentum to lift the embargo began to dissipate. Yet, the EU as a whole has continued to shy away from overt criticism of China’s human rights record, in part to avoid losing commercial benefits from its most important trading partner.

In the end, the embargo remains because EU rules require consensus to lift it, not because of agreement on the exercise of EU normative power. Such divisions were evident again this year after “acrimonious” negotiations in which the UK and France – who wanted the option to supply rebel groups – blocked the consensus needed to renew the EU arms embargo to Syria. Yet consensus was strong among the remaining 25 members about preserving the embargo, even as decision-rules once again dictated the outcome.

EU arms trade norms still appear to be evolving, but they are clearly much weaker in practice than EU policy would suggest. Where EU foreign policy relies on member state implementation, existing national priorities or material interests may influence states’ choices. Amidst EU members’ budget tightening, these tensions are likely to continue and complicate the development of EU normative power.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bJcDSJ

_________________________________

About the author

Jennifer L. Erickson – Boston College

Jennifer L. Erickson – Boston College

Jennifer L. Erickson is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Studies at Boston College. Her research sits at the intersection of international security, political economy and global governance. She has been a research fellow at the SWP and WZB in Berlin and Dartmouth College, as well as a faculty affiliate at Harvard University. She holds a BA in Political Science from St. Olaf College and a PhD in Government from Cornell University.