Vladimir Putin has announced that the construction of the South Stream pipeline, which was intended to transport gas from Russia across the Black Sea to South East Europe, is to be abandoned. Marco Siddi assesses the winners and losers from the cancellation of the project. He writes that while the key winner is likely to be Ukraine, countries in South East Europe will lose out on potential transit revenues. He also argues that with the EU still reliant on gas imports through Ukraine, the end of South Stream should provide extra impetus to reduce the share of fossil fuels in the EU’s energy mix.

Vladimir Putin has announced that the construction of the South Stream pipeline, which was intended to transport gas from Russia across the Black Sea to South East Europe, is to be abandoned. Marco Siddi assesses the winners and losers from the cancellation of the project. He writes that while the key winner is likely to be Ukraine, countries in South East Europe will lose out on potential transit revenues. He also argues that with the EU still reliant on gas imports through Ukraine, the end of South Stream should provide extra impetus to reduce the share of fossil fuels in the EU’s energy mix.

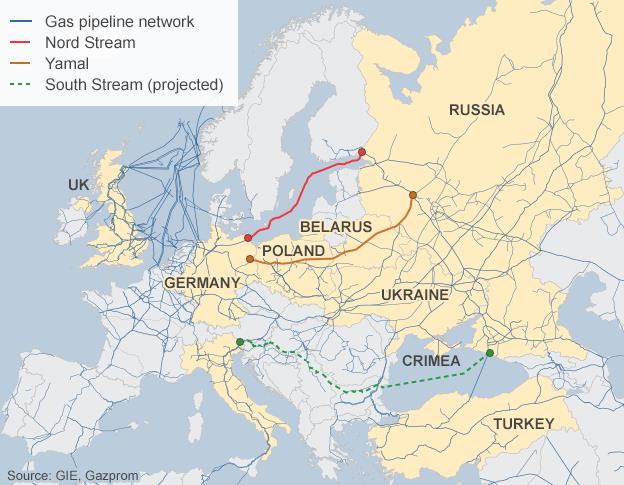

On 1 December, during an official visit to Turkey, Russian president Vladimir Putin publicly announced that the South Stream pipeline will not be built. South Stream – together with the Nord Stream and Yamal pipelines, which are already operational – was one of Moscow’s key projects to diversify the supply routes of Russian gas to the European Union and reduce reliance on Ukraine as a transit country.

Analysts agree that the confrontation between Russia and the EU in the Ukrainian crisis was the immediate reason behind Putin’s announcement. However, assessments on the strategic effects of Russia’s move – notably the question of who will benefit from it and who will lose out – were more controversial.

Figure 1: European gas pipeline network

Source: GIE, Gazprom

Losers: the South-East flank of Europe

There is little doubt that the cancellation of the South Stream project affected negatively the energy security of several South-East European countries. Serbia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovenia, Bosnia and Austria rely heavily on gas imports from Russia, which currently reach them through the Ukrainian energy corridor. Due to the clash between Russia and Ukraine, this corridor has become insecure, hence South-East European countries would have benefitted from a different import route.

New interconnectors with Central and Western Europe will help reduce reliance on the Ukrainian corridor, but their construction will take time and they might prove insufficient to replace gas flowing through Ukraine in the event of a serious crisis. Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and Slovenia also lost the transit revenues that they would earn if South Stream became operational. Moreover, the cancellation of the project was a blow to Italian and Austrian plans to become European gas hubs (both countries were indicated as potential ending points for the pipeline). The Italian energy company ENI lost a considerable source of revenue, as its subsidiary Saipem was to build the offshore section of South Stream in the Black Sea.

Winners: Ukraine, Turkey… and China

Ukraine is undoubtedly the main beneficiary from the cancellation of South Stream. Until alternative pipelines are built and Europe remains dependent on Russian gas, Ukraine will remain a key transit country for Russian exports. At the moment, 50 per cent of Russian gas supplies to Europe flow through Ukraine. Kyiv will continue to collect transit revenues and be able to demand higher fees if Moscow increases the price of the gas sold to Ukraine. For the upcoming winter, Kyiv can also count on a financial guarantee provided by the EU: following an agreement reached with Russia and Ukraine at the end of October, Brussels will act as guarantor of Ukrainian gas purchases and help to meet Kyiv’s outstanding debt with the Russian state company Gazprom.

While Italy and Austria lost a chance to become gas hubs, Turkey might take up this role – and considerably strengthen its strategic importance for European energy security – in the next five years. In his announcement on the cancellation of the South Stream project, Putin also stated that Russia will instead build a pipeline carrying 63 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year to Turkey (the same amount that would have been transported by South Stream). The project would replicate the Blue Stream pipeline, shown in Figure 2, which has transported gas from Russia to Turkey since 2003, but has more limited capacity (16 bcm/year).

Figure 2: The southern energy corridor and Blue Stream pipeline (click to enlarge)

Note: The pipelines shown are the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), and Blue Stream.

The construction of this new pipeline is still uncertain. Turkey’s dependency on Russian gas already accounts for 57 per cent of its needs, and the new pipeline would raise this to around 75 per cent – a prospect that could be unappealing for Ankara. Problems may arise also from negotiations on the price of gas (Putin’s proposed 6 per cent discount may not be enough for Turkish negotiators) and from geopolitical disagreements between Moscow and Ankara (notably on Syria and Cyprus).

However, if business interests and a shared critical attitude toward the West prevail, Putin and Erdogan may find a deal. As Turkey will also be a transit country for Azeri gas flowing to the EU via the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), which should become operational in 2018, Brussels may soon find itself in a position of higher dependence from both Ankara and Moscow for its energy security.

Despite its distance from the European energy arena, China may also benefit from the cancellation of South Stream. The project would have demanded large financial resources for Gazprom and, if implemented, it is unlikely that the company would have had sufficient funds to simultaneously build new pipelines carrying Siberian gas to China. Now Gazprom can concentrate its resources on the implementation of the agreement reached with China last May, which includes the provision of 38 billion cubic meters of gas a year for 30 years.

Russia and the European Union

At this stage, it is more difficult to tell whether Russia and the European Union will gain or lose from the cancellation of South Stream. As far as Russia is concerned, this may sound paradoxical, as the project was Moscow’s brainchild. Gazprom has lost an opportunity to further strengthen its position in the EU energy market.

However, from an economic viewpoint, the construction of South Stream made little sense at a time when European gas demand is dwindling and gas prices are low. South Stream was primarily a political project and had already achieved one of its key political aims: derailing the Nabucco project and perpetuating the European Union’s dependence on Russian gas.

Moreover, Putin’s decision to shift gas exports toward Turkey may have a similar political function: a new Russia-Turkey pipeline may compete with TANAP and reduce its economic viability. To pursue this aim, Moscow has already put pressure on Turkmenistan not to supply TANAP (Azeri gas supplies are limited and Turkmeni gas would strengthen the economic rationale of the pipeline).

For the European Union, the cancellation of South Stream implies continued reliance on the Ukrainian corridor for Russian gas supplies, which is subject to disruptions related to the rivalry between Moscow and Kyiv. If a new dispute leads to the interruption of the flow of gas, or if Ukraine is unable to pay for its gas imports from Russia, the EU will have no other choice but to mediate and, most likely, finance Kyiv’s gas consumption.

On the other hand, the cancellation of South Stream could have positive implications for the European Union if it leads to a broader reconsideration of its energy policy, which continues to prioritise fossil fuels. Policies aimed at reducing the share of all fossil fuels in the EU’s energy mix (regardless of their country of origin) would both make the Union less dependent on external suppliers and speed up its transition to a low-carbon economy.

Unfortunately, decision-makers in Brussels do not seem very keen on these objectives, as shown by the very modest goals of the 2030 framework for climate and energy policies. Instead, in many EU countries resources and discussions have continued to focus on highly uncertain, costly and polluting projects, such as the extraction of shale gas or boosting the coal industry.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Harald Hoyer (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1zwkLpk

_________________________________

Marco Siddi

Marco Siddi

Marco Siddi obtained a PhD in Politics at the University of Edinburgh in September 2014 and is currently research associate at the CRENoS institute in Cagliari. His research focuses on EU-Russia relations.