Poland will hold both presidential and parliamentary elections in 2015. Ahead of the elections, Aleks Szczerbiak writes on the parties of the Polish left, who will compete against the two largest parties in Poland, the centrist Civic Platform (PO) and the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS). He notes that following a series of disappointing election results, the Polish left is facing a deep crisis and may need to develop a completely new strategy if it is to challenge the two mainstream parties in 2015.

Poland will hold both presidential and parliamentary elections in 2015. Ahead of the elections, Aleks Szczerbiak writes on the parties of the Polish left, who will compete against the two largest parties in Poland, the centrist Civic Platform (PO) and the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS). He notes that following a series of disappointing election results, the Polish left is facing a deep crisis and may need to develop a completely new strategy if it is to challenge the two mainstream parties in 2015.

All things considered, 2014 was a disastrous year for the Polish left. After nearly a decade in the political wilderness, it entered 2015 in deep crisis and with a real chance that no left-wing parties will be elected to parliament in the Polish parliamentary election, which is due to take place in the autumn.

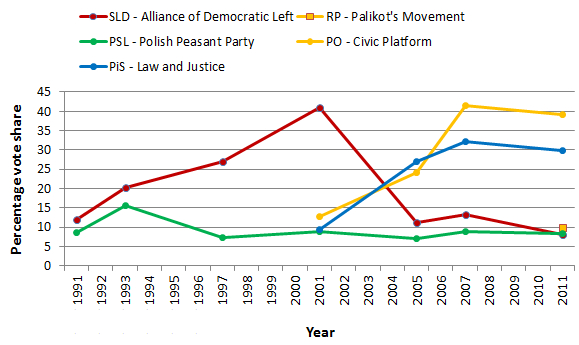

For the last decade the Polish political scene has been dominated by the centrist Civic Platform (PO), currently the main governing party, and the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party, the main opposition grouping. The Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), the once-powerful communist successor party which governed Poland from 1993-97 and 2001-5, has been in the doldrums since its support collapsed in the 2005 parliamentary election following the party’s involvement in a series of spectacular high level corruption scandals. The chart below shows how the party’s vote share has declined during this period.

Chart: Percentage vote shares for selected parties in Polish parliamentary elections (1991 – 2011)

Note: Chart compiled using data from the Political Data Yearbook

At the most recent 2011 parliamentary election the SLD suffered its worst ever defeat, slumping to fifth place with only 8 per cent of the vote, and there were question marks over its future survival. At the same time, a challenger emerged on the centre-left in the form of the anti-clerical liberal Palikot Movement (RP) which came from nowhere to finish third with just over 10 per cent of the vote. The Movement was formed at the end of 2010 by Janusz Palikot, a controversial and flamboyant businessman, and one-time Civic Platform parliamentarian.

However, when Leszek Miller, who was previously Democratic Left Alliance leader from 1997-2004, took over the leadership following its 2011 election drubbing he steadied nerves and restored some sense of discipline and purpose to the party. Mr Miller is a wily political operator who, in his heyday, led the party to victory in the 2001 parliamentary election and served as prime minister of Poland from 2001-2004, overseeing the country’s accession to the EU. By the start of 2014, the Alliance appeared to have recovered ground and emerged as the main left-wing challenger and ‘third force’ in Polish politics, with most polls suggesting that its support was hovering around the 10-15 per cent mark. The party was looking to confirm this position in the May European Parliament (EP) election and possibly even to offer a serious challenge to the two main parties.

Mr Palikot’s star wanes

Meanwhile, Mr Palikot’s party failed to capitalise on its 2011 election success, struggling with its political identity and finding it difficult to decide whether it really was a left-wing party at all or more of an economically and socially liberal centrist grouping. While Mr Palikot clearly had a talent for attracting substantial media interest in his political initiatives, which had helped him to shake up the Polish political scene, many Poles still regarded him as an unpredictable maverick who used coarse, often brutal, rhetoric and whose political initiatives lacked consistency.

At the end of 2013, Mr Palikot re-launched his party as ‘Your Movement’ (TR) and promised to tone down the strong anti-clericalism and social liberalism on which his earlier electoral success was based, while placing greater emphasis on free-market economics. However, re-branding the party simply further confused its remaining supporters and it continued to bump along at around 5 per cent in the polls, the threshold for parties to secure parliamentary representation.

Mr Palikot’s party had an even more miserable year in 2014. He tried to regain the political initiative and broaden out his party’s appeal by contesting the EP election as part of the broader centre-left ‘Europa Plus Your Movement’ (EPTR) electoral coalition. Mr Palikot originally hoped that Europa Plus would benefit from the (at least nominal) sponsorship of Aleksander Kwaśniewski, a very popular Democratic Left Alliance-backed two-term President of Poland (1995-2005) and one of the few Polish political figures of international standing. Many commentators saw Mr Kwaśniewski as the one politician with the potential to transform the Polish left’s electoral fortunes.

In fact, Mr Kwaśniewski’s involvement in the initiative was, from the outset, half-hearted to say the least and on occasions he appeared more of a liability than an asset; during much of the campaign he was mired in controversy over his business links with Ukrainian oligarchs. In the event, the EP election ended in disaster for Europa Plus which finished seventh securing only 3.6 per cent of the votes. Even Mr Palikot acknowledged that the former President’s ability to sway Polish voters was actually very limited and Europa Plus, which was almost-certainly Mr Kwaśniewski’s last major intervention in Polish domestic politics, fell apart in the wake of its electoral drubbing. Moreover, 2014 also saw Your Movement’s parliamentary group implode as 21 of its deputies defected to other parties and, by the end of the year, its caucus was reduced from the 40 parliamentarians who were elected from Mr Palikot’s party lists in 2011 to just 15 members.

The end in sight for Mr Miller’s party?

Nonetheless, in spite of seeing off the Palikot challenge and emerging as the main standard bearer of the left, the Democratic Left Alliance was not able to capitalise on this and has continued to lag well behind the two main parties in the polls. Mr Miller’s party secured third place in the EP election but with only 9.4 per cent of the vote, well short of the 15 per cent that it was hoping for (the party won 12.3 per cent in 2009), and lost two of its seven MEPs.

Critics argued that there was a limit to how far the party could go under Mr Miller’s leadership and that he lacked any clear strategic vision of how to expand its base and move support up to the next level. Indeed, there was worse to come in the November local elections, which were a disaster for the Democratic Left Alliance. In the elections to Poland’s 16 regional assemblies – the best indicator of national party support – the party finished fourth and saw its vote share fall from 15.2 per cent in 2010 to only 8.8 per cent, while its seats were slashed from 85 to 28. It was scant consolation that Mr Palikot’s party was not even able to register candidate lists in all of the regions.

Like all the main parties, the Democratic Left Alliance, and Polish left more generally, faces two formidable electoral challenges in the coming year. The first of these is the summer presidential election. Knowing that it faces almost-certain defeat at the hands of the popular Civic Platform-backed incumbent Bronisław Komorowski, the Alliance has struggled to find a high profile, party-aligned figure willing to contest this election. This included Mr Miller who ruled himself out at an early stage knowing that a poor result would weaken his already precarious grip on the party leadership.

In December, he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the party to support the candidacy of Ryszard Kalisz, who was at one-time one of the Alliance’s most popular parliamentarians. Mr Kalisz faced hostility from regional party bosses who regarded him as a renegade following a flirtation with Mr Palikot which led to his expulsion from the Alliance in 2013; he went on to stand on the Europa Plus ticket in the EP election. (In the event, in January 2015 the party selected a political unknown, 35-year-old historian and TV personality Magdalena Ogórek, as its presidential candidate.) For his part, Mr Palikot also announced his intention to stand in what will almost certainly be his last hurrah. Unless he can think of a way of once-again radically re-inventing himself, Mr Palikot appears to be finished as a major actor on the Polish political scene.

The most important challenge will, of course, be the autumn parliamentary election, whose outcome will determine the shape of the Polish political scene for years to come. Assuming he survives the presidential election, the autumn poll will be ‘do or die’ for Mr Miller and possibly even for the Democratic Left Alliance itself. If the party can recover ground and get itself into a position where it could be a pivotal member of a two or three-party Civic Platform-led coalition government, then this could provide it with a lifeline and mean that Mr Miller can end his political career as deputy prime minister or possibly speaker of the Sejm, the more powerful lower house of the Polish parliament, the second most senior Polish state office.

Entering a governing coalition with Law and Justice is highly unlikely given that the two parties are bitter rivals but not totally inconceivable. Last November, in a hitherto unprecedented meeting of minds, they joined forces to question the accuracy of the regional election results. On the other hand, given its recent difficulties there is a real chance that the Alliance may not even cross the 5 per cent threshold which would not just mean an ignominious end to Mr Miller’s career, but could herald the demise of a party that was the dominant force in Polish politics for much of the 1990s and early 2000s.

The left’s electoral-strategic challenge

More broadly, while various surveys have put the number of Poles who identify themselves as being on the political left at around 25-30 per cent, the bigger, over-arching electoral-strategic challenge faced by the Polish left is to develop an appeal that can bring together its two potential bases of support: socially liberal and economically leftist voters. Socially liberal voters tend to be younger, better-off, prioritise moral-cultural issues such as reducing the influence of the Catholic Church in public life, and are often quite economically liberal as well. They were at one time Mr Palikot’s core electorate and many of them still support Civic Platform. Indeed, some analysts argue that Civic Platform ‘borrowed’ many of these potential centre-left voters, who supported the party as the most effective way of keeping Law and Justice out of office, but clearly it has no intention of giving them back.

The economically leftist electorate, on the other hand, tends to be older and more culturally conservative; indeed, for this reason even many of those who are nostalgic for the job security and guaranteed social minimum that they associate with the former communist regime often support right-wing parties such as Law and Justice. Arguably the only deep social roots that the Polish left, and Democratic Left Alliance in particular, have are among those steadily declining sections of the electorate that have some kind of interests linking them to the previous regime, such as families connected to the military and former security services.

The Polish left finished the year pretty close to rock bottom; indeed, some commenters argued that the demise of the Democratic Left Alliance and current crop of left-wing elites were inevitable and even desirable. The left, it is argued, needs to develop a completely new political formula and a new generation of left-wing leaders if it is renew itself and mount an effective long-term challenge to the Civic Platform-Law and Justice duopoly.

For example, some are investing great hopes in figures like Robert Biedroń, a one-time Democratic Left Alliance activist who was elected from Mr Palikot’s party lists in 2011 as Poland’s first openly homosexual parliamentarian. Last year, in a high profile contest that was one of the few rays of hope for the Polish left in the November local elections, standing as an independent Mr Biedroń ran a clever campaign based on grassroots ‘pavement politics’ to unexpectedly win the election as mayor of the northern Polish city of Słupsk. However, at the moment he is more of a political celebrity with a knack for attracting publicity than potential future leader. The fact that it had to clutch at such rare and isolated examples of political success exemplifies the dire state that the Polish left found itself at the end of 2014.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: A version of this article originally appeared at Aleks Szczerbiak’s personal research blog. The article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Lukas Plewnia (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1xYvBiF

_________________________________

Aleks Szczerbiak – University of Sussex

Aleks Szczerbiak – University of Sussex

Aleks Szczerbiak is Professor of Politics and Contemporary European Studies at the University of Sussex. He is author of Poland Within the European Union? New Awkward Partner or New Heart of Europe? (Routledge, 2012) and blogs regularly about developments on the Polish political scene at http://polishpoliticsblog.wordpress.com/