One of the key debates in the context of the UK’s EU referendum is whether a Brexit would help or hinder the British economy. Swati Dhingra argues that while both sides of the referendum campaign have a tendency to exaggerate figures, the last 40 years of data demonstrate clear economic benefits from the UK’s EU membership.

One of the key debates in the context of the UK’s EU referendum is whether a Brexit would help or hinder the British economy. Swati Dhingra argues that while both sides of the referendum campaign have a tendency to exaggerate figures, the last 40 years of data demonstrate clear economic benefits from the UK’s EU membership.

At midnight on 1 January 1973, a Union Jack flag was raised at the European headquarters in Brussels to mark Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC). More than forty years later, Britain is getting ready for another referendum to decide on its continued membership of the European Union. During the run up to this referendum, much has been said about the political consequences of leaving the EU (a so-called ‘Brexit’). But less attention is given to the economic consequences of Brexit. Like the Out campaigners of the 1970s, Brexit campaigners claim that membership in the EU harms British workers. Forty years of data do not support this claim, and continued membership is unlikely to change this economic reality.

There is a lot of uncertainty over which policies will prevail if Britain exits the EU. So the Brexit debate has been dominated by polarised economic forecasts that rely on policy assumptions which seem to confirm the prior convictions of the experts conducting these studies. For example, an EU study estimates that the British economy would have a net gain of 2 per cent of GDP per year from continued membership, while a UKIP study estimates a net loss of 5 per cent.

The economic reasoning given on both sides sounds very much like the debate over Britain’s entry into the EEC in 1973. There were fears then that joining the EEC would increase consumer prices and hurt the earning prospects of British workers through trade, regulations and immigration. The current public debate echoes similar concerns via equally charged voices. But what is missing from the debate today is the benefit of hindsight. We now have forty years of data to examine what really happened to prices and jobs after Britain joined the Single Market – and the data show British workers benefited from lower prices and higher real wages.

The single market reduced barriers to trade among member countries. This increased competition among firms who reduced the markups (prices net of costs) they charged to consumers. Looking at manufacturing goods across ten EU member states, the markups charged by firms fell from 38 per cent to 28 per cent of costs. The impact of the single market on consumer prices is also evident from the reduction in price dispersion across European cities. As markets integrate, consumers get easier access to markets in other countries which harmonises prices of similar products across countries. Looking at local prices of dozens of items such as ‘white bread (1 kilogram)’, ‘men’s haircut’, and ‘cardigan sweater’, price dispersion fell sharply for goods that are traded across countries in the single market, reaching levels similar to the price dispersion across cities in the United States.

Lower prices would have been of little relief to British workers if competition from the single market had harmed their job prospects. But in fact, British businesses expanded production, as they gained better access to European markets. The single market entailed a number of product market changes such as a reduction of non-tariff barriers to trade within Europe and effective enforcement of internal market rules. These product market reforms increased real wages of British workers, and aggregate unemployment fell by an estimated 0.7 percentage points. Firms also intensified their research and development activities, which in turn increased aggregate productivity in manufacturing.

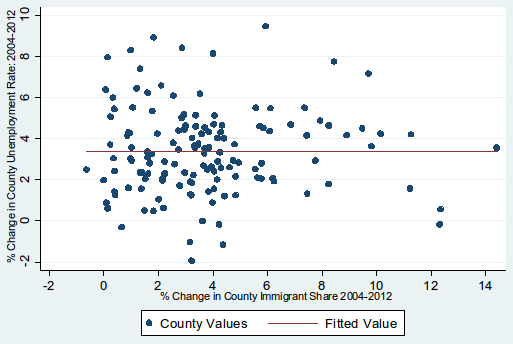

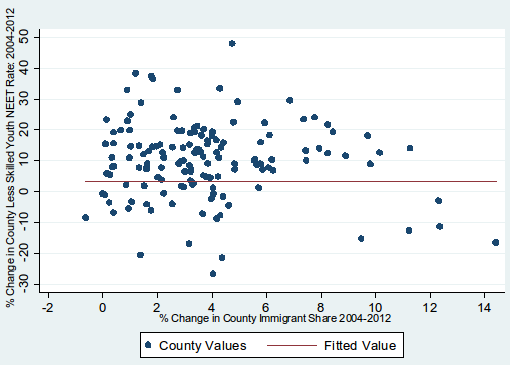

The single market lowered barriers to movement of people within the EU. Just like today, this was a hot-button issue which evoked strong fears that European immigrants would displace British workers. Over a third of the immigrants in Britain are from EU countries, but there is still no compelling evidence of an overall negative impact of immigration on jobs or wages of British workers. Even after the EU expansion and the recent financial crisis, counties with the largest increases in immigrants experienced neither larger nor smaller increases in UK-born unemployment and wages, as shown in Figure 1 below. This is also true for low-wage workers, who might be considered most vulnerable to job pressures from immigration.

Figure 1: UK-born unemployment rate (2004-12)

Note: The figure illustrates that there is no relationship between changes in immigration and unemployment for UK-born workers. Source: Wandsworth (2015)

Figure 2: UK-born ‘less skilled youth NEET rate’ (2004-12)

Source: Wandsworth (2015)

Going by this evidence, the single market did not hurt British workers. And there are reasons to believe that continued membership would have further beneficial effects. Moving forward, the EU will focus on policy changes, such as lowering barriers to trade in services, which are expected to reduce consumer prices and expand employment opportunities in Britain.

Compared to trade in goods, there are still substantial barriers to trade in services across EU member states. One piece of evidence is that the forces which resulted in lower markups for manufactured goods from the single market reforms seem to be absent in the services sector. So British consumers would have much to gain from future integration of services within Europe. Another piece of evidence is that product regulations in the importing country are negatively related to the volume of trade in services, but not to trade in goods. Britain is a net exporter of services to the EU, and a future reduction in barriers to trade in services would provide export opportunities for British firms. Conservative estimates from the Centre for Economic Performance show the expected gains would be between 1 and 3 per cent of British GDP.

Missing out on future integration within Europe would limit Britain’s growth potential. At this point, integration is not a matter of lowering tariff rates. It requires policies, such as hammering out regulatory differences in services provision, which would be extremely difficult if Britain is not a fully-fledged member. Even the most vocal supporters of Brexit agree that Britain should keep its borders open to trade with the EU. What they often overlook is that membership did not hurt British workers in the past, and continued membership would ensure that Britain has a voice in negotiations over future EU policies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is also cross-posted at UK in a Changing Europe. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Andrew Gustar (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QRCWxe

_________________________________

Swati Dhingra – LSE

Swati Dhingra – LSE

Swati Dhingra is Lecturer at the London School of Economics, Department of Economics and Centre for Economic Performance.

The vast majority of business in the United Kingdom has absolutely nothing to do with the EU. In percentage terms the interaction is between 10 & 15% of the economic activity of the UK that exports the rest of the activity revolves around a robust internal UK market, the market that the EU needs to trade with to avoid catastrophic damage to the green shoots that are showing in the Eurozone. We hear 3 million UK jobs could be effected it a wall went up between the UK & EU (Utter Tripe) but if the figures were true then between 5 & 6 million EU jobs would be at risk because the economic activity is weighted in exports from the EU to the UK rather than from the UK to the EU. You need to accept that companies like Airbus need wings & Engines, they won’t sell many to the Chinese, Indians or Iranians without them will they? These exports are classed as exports to the EU even though they are going to an end user from outside the EU much like cars transhipped through Rotterdam & Antwerp to China, India, the Gulf etc are also classed as exports to the EU which they clearly are not. If the EU cuts trade how will they get their exports to Ireland? the traffic goes through the UK. If the EU stops imports of UK goods their days of Fish & Chips will be over for the masses as most of their fish comes from British waters do I need to go on?

Joe: most of what you’ve written here is a rehearsed debunking of arguments that aren’t actually contained in the article. The “3 million UK jobs” line, for instance, is a soundbite that goes back to the early 2000s. There’s no mention of it anywhere in the text. The Rotterdam effect is a decades old line designed to muddy the waters whenever anyone cites another soundbite about roughly half of our exports going to the EU. Again, nobody has mentioned that here. In fact much of the gains being talked about are related to services, which aren’t “shipped through Rotterdam” for obvious reasons. If you want to argue against something it really is necessary to read it first and come up with a suitable rebuttal.