We are now entering the last month of campaigning before the first round of voting in the French presidential election on 23 April, with Marine Le Pen still leading in many opinion polls for the first round, but behind in polling for the second round. Ben Margulies assesses some of the key factors in her favour, and several more reasons why she is ultimately likely to end up disappointed.

We are now entering the last month of campaigning before the first round of voting in the French presidential election on 23 April, with Marine Le Pen still leading in many opinion polls for the first round, but behind in polling for the second round. Ben Margulies assesses some of the key factors in her favour, and several more reasons why she is ultimately likely to end up disappointed.

In the aftermath of Brexit and Trump, journalists, political scientists and, one imagines, hard-core survivalists have been asking where they will witness the next populist triumph. Italy, Germany and The Netherlands have all been mentioned – with the latter failing to deliver in elections on 15 March. But increasingly, the key worry is France, and within France, the candidacy of the Front National’s Marine Le Pen.

In countries like Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, any populist leader would likely require some sort of coalition government to enter office. France, on the other hand, has a semi-presidential system; even if the Front fails to win an accompanying parliamentary majority, a President Le Pen would have considerable powers as the Republic’s chief magistrate.

So how likely is it that the Front National will win in the second round of a French presidential election, due in early May? How likely is it that Le Pen will follow in the footsteps of her fellow right-wing populist Donald Trump? I spent much of 2016 telling various media outlets that the United States did not have enough angry white voters to make Donald Trump president, so I am not going to rule out a Le Pen win. But I am still doubtful one will occur. There are some tangible reasons to believe Le Pen could win, but also several more reasons to believe she will probably fall short.

Les avantages

Corruption

Marine Le Pen is a populist, and populism, as Cas Mudde tells us, involves a distinction between a pure, homogenous people and a corrupt, equally homogenous elite. Le Pen benefits from the widespread sense that the French political elite is highly corrupt. The centre-right Les Républicains party has spent most of 2017 confirming exactly this popular suspicion, as its candidate, former prime minister François Fillon, battles accusations that he paid his spouse and children with French parliamentary funds for work they never performed. (The nepotism is not itself illegal; the fact that they failed to perform any work is.) Admittedly, Marine Le Pen herself faces charges of misappropriating funds from the European Parliament. However, her voters are less likely to consider the EU a legitimate public authority and hold her to account for it.

Stagnation

The French economy, and French society more broadly, have been described as “stagnant” since at least the 1990s – Jonathan Fenby wrote a book in that decade called France On The Brink. Perry Anderson wrote an essay on French déclinisme in the London Review of Books in 2004. The IMF states that French unemployment has averaged approximately 9 per cent since 1990, a period that covers the tenure of four presidents and 11 prime ministers. Decline and incompetence have been themes of French politics for decades, defeating presidents of both right (Chirac, Sarkozy) and left (Hollande). This provides an opening for populists and their message of “regeneration” and “redemption“, while making the whole political class look uniformly incompetent.

Neoliberalism

Fillon, at least initially, ran on a harshly “Thatcherite” programme, promising to eliminate half a million public-sector positions and to abandon the 35-hour week, while also carrying out €110 billion in spending cuts. Macron is more centrist, but his plans also call for a reduction in public-sector employment of 120,000 and cuts in corporation tax. The Front National, on the other hand, has moved steadily leftwards on the socio-economic scale in recent years, and Marine Le Pen can run against either Fillon or Macron as the candidate of the popular classes. In the run-off, she could end up taking working-class or public-sector voters who traditionally vote Socialist or for parties further to the left, but who probably will have no leftist option in the second round.

Terrorism

Radical-right populism thrives in an atmosphere of external threat. Fear accentuates cohesion in the national community and a desire for authoritarian solutions. Trump used this to great effect, and some studies have found that authoritarian leanings correlated with Trump voting, at least in the primary elections. Those studies also found that imminent threats tended to make voters respond in more authoritarian manners. Marine Le Pen is running for office in a country that is still under a state of emergency following several major terrorist attacks since the beginning of 2015; the sense of threat is much more evident and tangible than in the United States.

Les désavantages

Trump had a mainstream party – Le Pen does not

Many commentators credit Trump’s victory to his success at peeling off white-working class voters from the Democrats. Actually, relatively few former Democratic voters defected to the Republican candidate last year. Trump’s victory in large part depended on his ability to carry the bulk of voters who normally vote Republican. Orthodox partisan loyalty played a central role in Trump’s victory. (Notably, one of the most successful radical-right parties in Europe, the Swiss People’s Party, is an insider party that adopted a populist, anti-immigration platform late in its history.)

Marine Le Pen, on the other hand, leads an outsider party with distinctly anti-system and even anti-democratic roots. Historically, the Front National has lacked mainstream legitimacy, and she has had to undertake a years-long project of professionalisation and de-diabolisation to get to the point where she can lead French opinion polls. She simply lacks the credibility to appeal to a wider pool of centre-right voters.

Authoritarian and Catholic voters

Didn’t I just say these voted for Trump? Yes. But authoritarians are also very conventional. They are actually less likely to take a chance on outsider candidates. Dunn finds that, although nationalists favour radical-right populist parties, authoritarians do not necessarily. Had Trump run as an independent against, say, Republican nominee Ted Cruz, he might have had far less electoral success. Similarly, Le Pen may have a hard time peeling off loyal French Républicain voters, if they perceive her party as unconventional.

Fillon also has a strong appeal to specifically Catholic voters. Although there is certainly a strain of conservative Catholicism in the Front, Marine Le Pen does not represent it, and she has softened the party’s stances on certain “values” issues like abortion (tolerant) and same-sex relationships. Religious voters were less likely to choose her in the 2012 presidential elections.

Mainstream voters have another option to express their anti-elitism

Usually, populist parties represent the socially excluded, and these tend to be majoritarian or illiberal – another part of Mudde’s definition of populism is that populists demand the untrammelled execution of the popular will. These parties are usually democratic, but not liberal. This extremism, and the fact that these parties appeal to low-status groups, can limit their mainstream appeal.

But there are several cases in Europe of a curious hybrid phenomenon – an anti-elite party or candidate which condemns the existing political elite, but not the constitutional system as such – a sort of “liberal” or “centre populism.” In a way, this provides a kind of “internal opposition” for fed-up mainstream voters who do not feel socially excluded or harbour anti-system sentiments. Instead, they can vote for a sort-of insider who will do away with the system’s dead wood, but not the system.

In Spain, Ciudadanos fills this niche – a new-ish liberal centrist party with an attractive young leader. In France, Emmanuel Macron and his En Marche movement, currently running second in the presidential polls, takes on the role of internal opposition. Macron provides an outlet for middle-class protest voters who might have, in desperation, picked Le Pen – or low-information voters who simply see two protest candidates and have a vague sense that Macron is the more acceptable.

Run-offs

Remember, Trump also won because of the unusual American contraption that is the Electoral College; he lost the popular vote by 3 million. His 45.9 per cent of the popular vote is only very slightly higher than John McCain’s share in 2008. Marine Le Pen, on the other hand, has to get 50 per cent plus 1, and very few populist parties in any European countries have ever achieved this, in Eastern or Western Europe. Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz did in Hungary in 2010, but not 2014. Austria’s Freedom Party famously failed to win two different presidential runoffs in 2016.

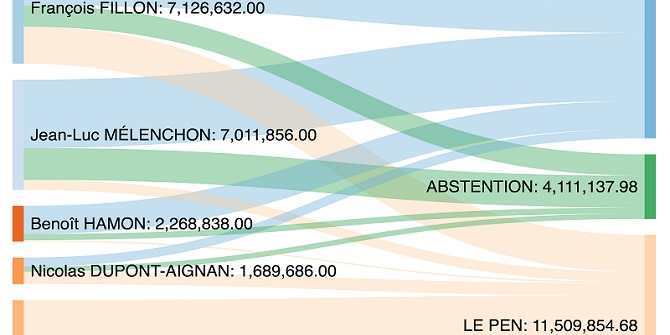

The Front National has failed to cross less formidable hurdles on a number of occasions in lower-order elections. In municipal and regional elections, candidates merely need a plurality in the second round (if more than two lists qualify, as can happen). But in 2014, the party won “11 towns … barely one town in one hundred with over 10,000 inhabitants, barely one commune in one thousand with over 1,000 inhabitants.” It failed to win a single region in the 2015 elections for that level of government. And these were low turnout, second-order elections where a Front victory would be easier for voters to stomach.

The Trump effect

If the media and public analogise Marine Le Pen to Donald Trump, then that would certainly flatter the US leader. Le Pen herself has praised Trump. But it only helps Le Pen if Trump is popular in France. Nothing suggests that he is; an Economist poll published in November 2016 found that Trump would have won maybe 15 per cent of the French vote in a match-up against Hillary Clinton. Among Front voters, that figure rose to about 30 per cent; he was slightly less popular among them than Clinton. Individual Trump-like policies are popular – about three-fifths of French respondents favour a ban on immigration from Muslim countries, according to a Chatham House poll published in the wake of the travel ban. But that does not mean that they want a president aligned with Donald Trump.

So will Marine Le Pen be the next populist to stage a triumphal entry into a presidential palace? Though only fools would discount anything in politics these days, it seems unlikely. The Front’s electoral record shows it repeatedly failing to win runoff elections in France. Nor does Marine Le Pen have the sort of access to mainstream centre-right voters that (just) carried Donald Trump to the White House. She may come close, but at least in 2017, she will more likely than not fail to be elected the Fifth Republic’s eighth president.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

About the author

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Warwick.

precisely because it’s a 2 rounds elections does it make a non-starter to think of a Front National presidential victory : it’s as likely as betting on aliens landing with their flying saucer in buckingham palace

next, even assuming that the Front National were to win the presidency, its party has no traction when MPs are voted in. that is less than 10% of the parliament is filled with Front National representative.

Again for the same reasons as you mentionned : the “Pacte Republicain”, where both right and left-leaning voters vote for the non-Front National candidate in any second round election.

and with no allies to form a coalition government (like Wilders in the Netherlands), the next Parliament will simply call for a motion to desist for “president” Le Pen and new elections to be called asap.

the “core voters” of Front National make up around 15% of the French electorate (think UKIP – hard right Tory). in the first round, many voters do give preference to radical (left and right) candidates as a protest vote, but soon vote mainstream in the 2nd round.

it might even be that Le Pen doesn’t make it to the the “nd round as happened in the previous presidential election when she was given as a “secure” challenger to Sarkozy (and yet it was Hollande that made it)

Expecting the Front National to win with a majority is like expecting UKIP to win with a majority in the UK. It’s a long shot, but it might happen.

I think people confuse Trump’s victory and Brexit with European presidential elections. It’s not a binary choice between Trump vs Hillary or Leave vs Remain. Many parties are involved. If France was to have a referendum, then I’d understand the immense interest a bit more.

The only way that she might win is if she makes it to the second round. And then we’ll have a binary choice between her and perhaps Macron?

Assuming Le Pen is unpopular would be the first mistake, especially if she ends up against Macron with no experience/who appeared out of nowhere… Things could get interesting, but it depends how many of her supporters are silent supporters. Now it seems like she has gained support, but we don’t really know how much she gained.