On 24 June, the Italian government announced that it would intervene in two banks, Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza. Both banks were to be wound down with each bank’s good assets being sold to the Intesa Sanpaolo banking group. Mara Monti compares the affair with the case of Spain’s Banco Popular, which was saved from collapse just a few weeks before, but using a notably different approach.

On 24 June, the Italian government announced that it would intervene in two banks, Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza. Both banks were to be wound down with each bank’s good assets being sold to the Intesa Sanpaolo banking group. Mara Monti compares the affair with the case of Spain’s Banco Popular, which was saved from collapse just a few weeks before, but using a notably different approach.

The new European resolution framework represents a large improvement on the process that prevailed before and during the crisis. The aim of regulators is to make the system safer, and to create a process where important financial institutions can fail in an orderly manner. To preserve public finance and market discipline, the principle of the post-crisis financial regulations is that no private financial institution should be viewed by markets as being too important to be allowed to fail.

However, banking resolution involves difficult trade-offs between creditors and taxpayers, between market discipline and financial stability, and between sovereign solvency and political risk. Allocating losses to private creditors improves incentives and protects taxpayers, but it can fall disproportionately on some investors and create short-term financial instability.

In the cases of the Spanish Banco Popular and the Italian Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza, there appear to have been two different measures adopted for solving the same problem. One has been paid by private bondholder and the other by taxpayers. Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza were not ‘too big to fail’, nevertheless they have been saved thanks to state aid. The decision taken by the Italian government on 24 June to intervene in these troubled banks is a domestic resolution rather than a European one. In fact, the path the government decided to pursue, in agreement with the Commission and the ECB, is to pursue the liquidation of the two banks according to Italian insolvency procedures, which gives more flexibility to safeguard bond investors and depositors.

A different set of measures entirely were taken for Spain’s Banco Popular Espanol, which collapsed before the intervention of Spanish bank Santander. In this case, the European Single Resolution Board (SRB), the Eurozone agency responsible for dealing with bank crises, agreed to cancel its common stock and additional capital instruments, and Santander stepped in to buy its remaining assets and liabilities for one euro. Depositors and senior bondholders were saved, but shareholders and investors in capital instruments, who knew the risks they were taking, were wiped out. Senior bondholders didn’t lose any money and no state aid was required.

This was not so in the case of the Italian banks, where the government offered guarantees of up to 12 billion euros to cover losses from the two banks’ bad loans and offer aid of 5.2 billion euros, including 4.8 billion euros for Banca Intesa, a stronger Italian lender, that acquired for 1 euro their good assets. As for Montepaschi last December, the Italian government agreed to pump 5.2 billion euros of state aid while Banca Intesa, following the acquisition, needs to maintain its capital ratios and pay for the layoff of around 3,500 employees.

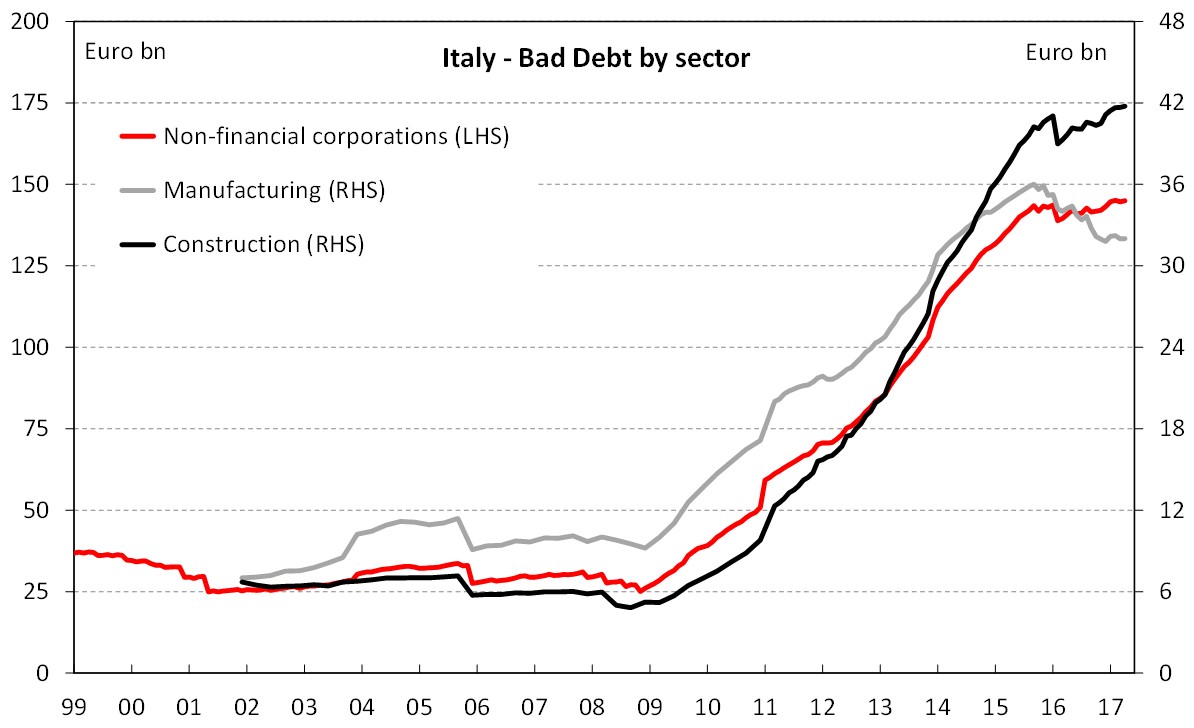

Figure: Bad debt in Italy by sector

Source: Bank of Italy; Thomson Reuters Datastream

The decision over the Veneto banks came after the European Central Bank said the banks were failing, but what would be the impact of the banks failing on the Italian economy? There would be very little impact as it happens. In fact, the two banks have a combined market share in Italy below 2%, making it unclear whether their failure would lead to a serious disturbance in the Italian economy. The aim of preserving stability and avoiding bank failures is one of the conditions for permitting a precautionary recapitalisation under the BRRD (Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive). In this case, the SRB decided that the resolution of the banks under the new EU rules was not “warranted in the public interest”.

In fact, the two banks didn’t meet the criteria for a precautionary recapitalisation as was the case for Montepaschi. Nevertheless, the shareholders and capital instrument holders of Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca will be wiped out (as for Montepaschi, in case of misselling some restore will be considered), while its senior bondholders will be fully preserved, much to their own surprise as the market reacted: Vicenza’s 750 million 2020 senior note was trading at around 85 cents on the euro on Friday, but soared up to 118 cents on Monday. Veneto’s 500 million 2019 senior bond surged from 88 cents to 103 cents over the same period, near Intesa bond in the secondary market. As for Spain’s Banco Popular, senior bonds were protected, but at the Italian taxpayer’s expense rather than at the expense of private bondholders.

The case of the Italian banks is peculiar compared to the Spanish banks, with their credit being mostly linked to SMEs rather than to real estate that is the source of nonperforming loans, instead of loans to households or real estate developers. The other important aspect of the Italian banking crisis is the exposure of retail investors to junior bank bonds. As of the third quarter of 2015, Italian savers held about 29 billion euros in subordinated bank bonds (according to the Bank of Italy). Overall, the exposure of Italian households to subordinated bonds, senior unsecured bonds, deposits above 100,000 euros, was around 10% of their financial assets, with subordinated bonds representing about 1% of exposure.

Selling junior bonds to retail investors was a way for Italian banks to access cheap funding during the financial crisis. Between July 2007 and June 2009, 80% of Italian banks’ bonds were sold to retail investors. Many investors may not have understood the risks they were taking and the misselling seems to have been on a large scale. This is why a political intervention may put at risk the European resolution framework.

Since the financial crisis, governments have provided various types of support to their financial sectors under the state aid framework. The case of Monte Dei Paschi shows that the dispositions of Article 34 of the BRRD relating to precautionary recapitalisation can be interpreted in a broad manner even in the absence of financial instability, as shown by CEPR in their recent report. While some discretion is useful, there is a danger that too much discretion, as the last Italian case underlines, can undermine the credibility of the instrument.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Mara Monti – LSE, European Institute

Mara Monti – LSE, European Institute

Mara Monti is Visiting Fellow at the LSE’s European Institute and a journalist at Il Sole 24 Ore, Italy’s leading financial/economic newspaper, based in Milan. She completed an MSc (Econ) in Politics of the World Economy at LSE career in journalism, specialising in the financial sector. Over the past 16 years, she has been part of the financial team at Il Sole 24 Ore, writing extensively on financial issues, sovereign crisis and monetary policy issues. Prior to joining Il Sole 24 Ore, Mara worked as editor-in-chief for international news agency Dow Jones Telerate in Milan. She wrote several books investigating the bankruptcy crisis of the past ten years and probing into financial scandals.