How does European integration affect the welfare state? Drawing on a new study, Tobias Tober highlights two conflicting effects that the integration process generates in relation to welfare spending. While economic integration increases popular demand for social spending, political integration decreases its supply, effectively breaking the link between social policy preferences and social policy output.

For decades, a prominent line of critique has held that the European integration process is strongly biased towards economic interests and neglects the social policy dimension. Proponents of this view argue that the asymmetry between market-making and market-correcting efforts has resulted in a European agenda of labour market deregulation and privatisation. These authors claim that the few remaining national options under the alleged liberalisation regime of the European Union are on the supply side, including increasing wage differentiation and welfare state cutbacks (e.g., here and here).

Given this longstanding critique, it is surprising that empirical studies have rarely tested the impact of European integration on the welfare state (see here for a review). Together with my co-author, Marius Busemeyer, we try to fill this gap in the literature in a recent study. We argue that European integration has non-complementary consequences for the political economy of welfare spending. While European economic integration increases popular demand for social spending, European political integration decreases the supply of social spending. Thus, the conflicting implications of European integration essentially break the link between social policy preferences and social policy output.

Our argument

On the demand side, we draw on an argument that is known as the ‘compensation thesis’. It claims that intensified economic integration increases economic insecurity among workers, which in turn triggers increased public demand for social insurance and redistributive compensation from the welfare state. In a nutshell, we highlight two major channels through which European economic integration may contribute to more economic insecurity.

First, the single market of the EU has increased economic competition and has created new exit options for mobile factors of production. These trends exert significant downward pressures on wages and employment conditions. Second, it is much more difficult for trade unions to organise effectively at the European level than in the national arena. Thus, their ability to protect workers from adverse market forces declines. Usually applied to globalisation, we argue that the individual-level logic of the compensation thesis is particularly relevant in the context of the EU because economic integration in the single market is reinforced by the process of political integration, which is heavily geared toward promoting the removal of trade barriers and the creation of harmonised markets.

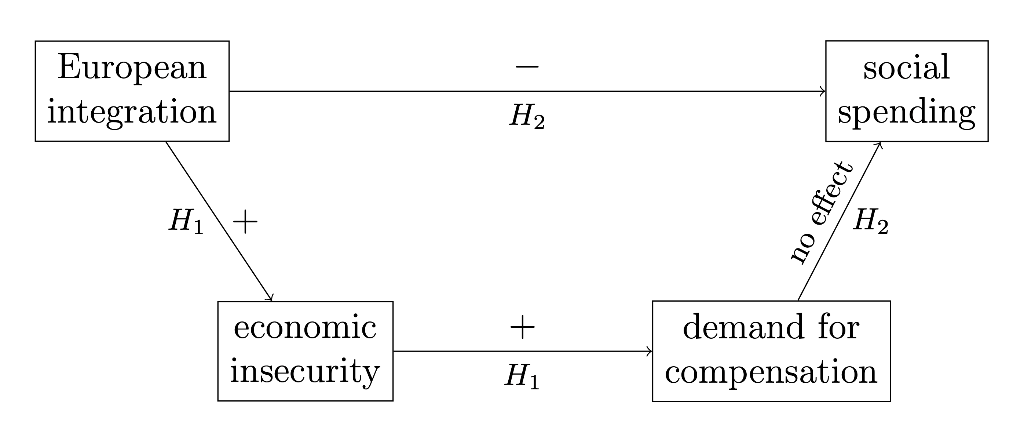

On the supply side, our argument focuses on the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and how its fiscal rules – the Maastricht convergence criteria and the Stability and Growth Pact – have a structurally constraining impact on member states. Although critics have questioned the effectiveness of these fiscal rules, empirical research has repeatedly shown that membership of the EMU depresses government spending, especially in the area of social policy (e.g., here and here). Thus, while European economic integration fuels public demand for compensation (indicated as H1 in Figure 1 below), European political integration delimits the fiscal leeway of national-level policymakers to supply social policy. European integration therefore provokes a mismatch between demand and supply, essentially breaking the opinion-policy link (shown as H2 in Figure 1).

Figure 1: European integration and the political economy of welfare spending

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy.

Empirical results

To test these hypotheses, we adopt a two-step approach. First, to estimate how individual demand for compensation responds to country-level variation in European integration, we apply a Bayesian mixed-effects modelling strategy that draws on five waves of the European Social Survey covering 22 member states between 2004 and 2012. We measure demand for compensation by an item asking respondents whether they agree with the statement that government should reduce income differences. The measure of European integration distinguishes between economic and political integration. The economic dimension captures openness to EU trade and the importance of EU trade to trade relations outside the EU. The political dimension combines information on institutional participation with data on member states’ compliance with EU law (see here for more detail).

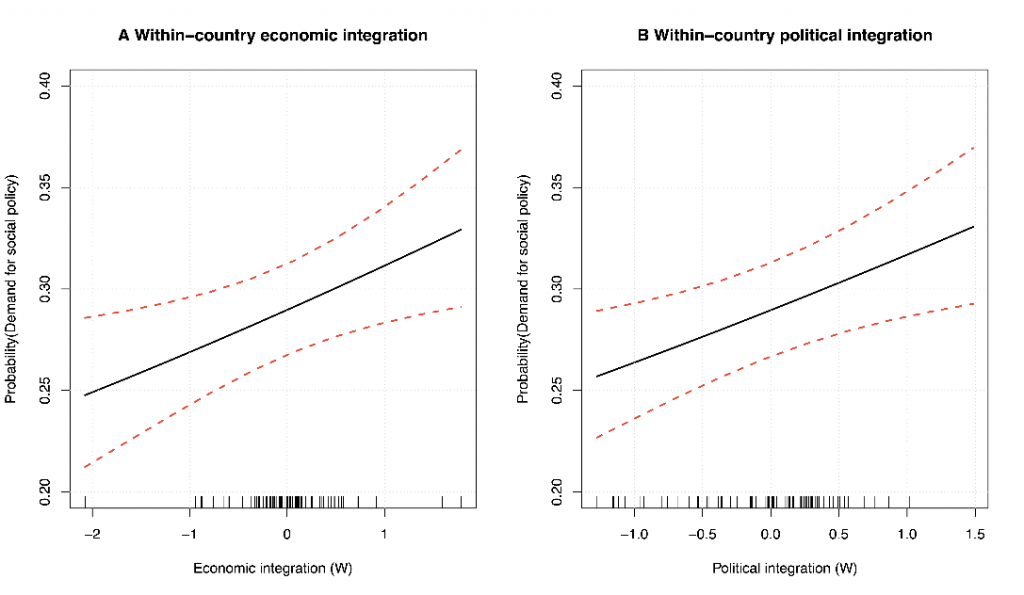

Controlling for a range of individual and country-level factors, we find that within-country changes in both economic and political integration are associated with more popular demand for compensation. To make the effects more tangible, Figure 2 presents average marginal predicted probabilities based on one of our models. For both economic and political integration, an increase of one standard deviation is associated with an increase in the predicted probability by about one percentage point. When we break down political integration into its two subindicators, we find that the effect is exclusively driven by compliance with EU law and not institutional participation. The major element of legal compliance is compliance with the rules of the single market. This suggests that the economic logic of the compensation thesis is particularly relevant in the context of the EU due to the legal reinforcement of European political integration.

Figure 2: Average marginal predicted probability of demand for social policy by within-country economic and political integration with 95% confidence intervals

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy.

In the second step of the analysis, we employ time-series cross-section models controlling for a battery of potential confounders, which regress data on government social spending on our measure of European integration. The results show that political integration has a depressing effect on social expenditure and that this effect is mostly driven by institutional participation, in particular membership in the EMU. Moreover, we find that aggregated social policy preferences have no statistically significant relationship with social spending, implying that governments are not responsive to citizens’ demands.

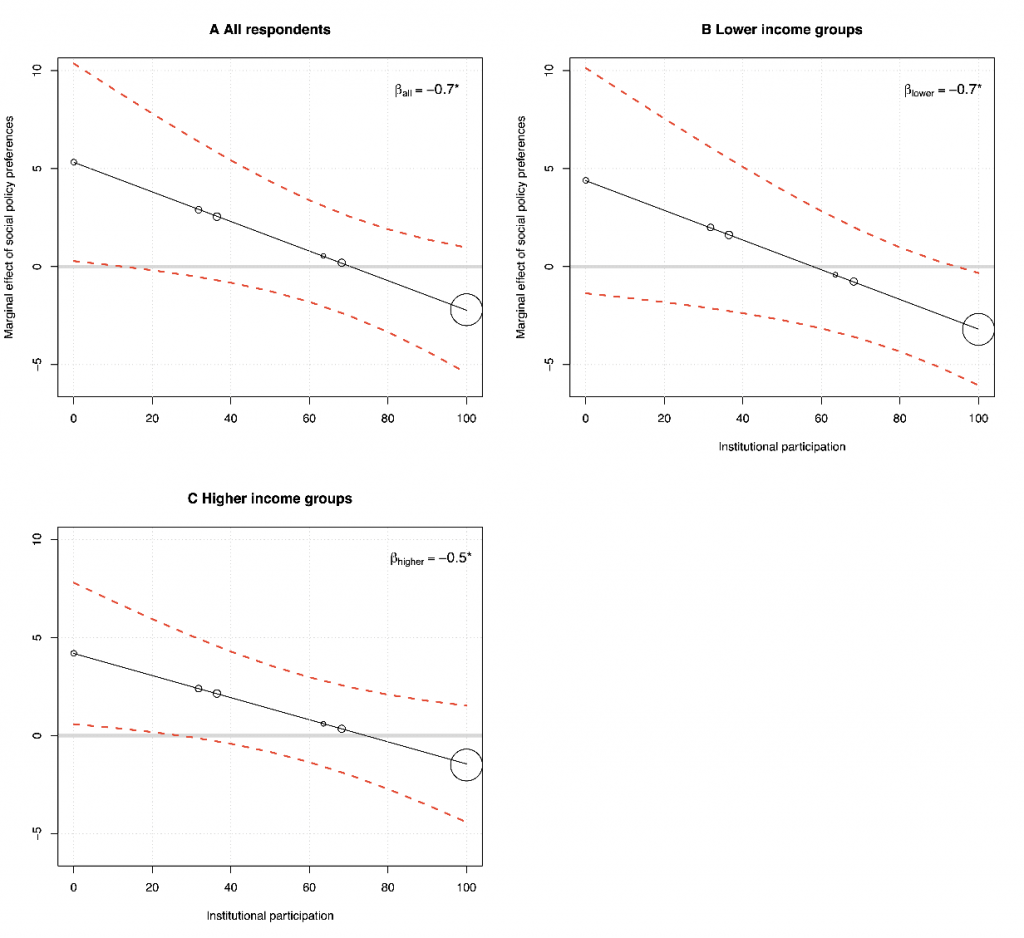

In Figure 3, we probe whether this lack of policy responsiveness is conditional on institutional participation in the EU, where a value of 100 indicates EMU membership. The results suggest that governments’ responsiveness to social policy preferences declines as institutional participation in the EU increases, with EMU members exhibiting no detectable (positive) association between popular demands and actual policy output (for lower income groups in Panel B, the association even appears to be negative in the EMU). Given the small sample size on which these interaction results rest, they have to be treated with caution. Nevertheless, we take the fact that the remaining variation in the data bears out the theorised relationship as suggestive evidence for our argument.

Figure 3: Marginal effect of social policy preferences on social policy supply conditional on institutional participation with 95% confidence intervals

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy.

We believe that these findings have important political implications. In the wake of the Eurozone crisis, various austerity measures were implemented that can be seen as a stricter continuation of EMU’s fiscal rules. At the same time, the crisis led to escalating levels of unemployment and a significant drop in wages in some of the member states. These developments suggest that the contradictory impact of European integration on the political economy of social policy persists and will potentially intensify in the future.

The growing mismatch between demand for social policy and actual supply may contribute to low levels of trust in national and European institutions, and thus undermine their perceived legitimacy. This would create further breeding ground for populist challengers to the European political system, in particular if the social dimension of the European integration process continues to be neglected.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy (co-authored with Marius R. Busemeyer)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council