While I was studying residents-turned-protesters against eviction in Shanghai, calculated risks and extra precautions were inevitable to carry out the research and protect my sources and myself. The nature of the project also complicated my relationship with the residents, and it was necessary to build both trust and boundaries with the residents to achieve the goals of the fieldwork, writes Qin Shao.

In January 2004, I started my first six months of field research in Shanghai for a book project, Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity. Since then and until 2012, I returned to China for fieldwork in most of the summers and frequently exchanged emails and phone calls with the residents as their cases were evolving. The book is thus largely based on the residents’ oral history, their lived experience, and the materials they had gathered and produced as well as my own observations and recordings of their activities in their own environment.

The challenges and constraints of my field research were determined by the nature of the project. The project was politically sensitive. It studies the impact of the massive demolition and relocation in Shanghai, especially that of the forced eviction or domicide—“the planned, deliberate destruction of home causing suffering to the dweller,” as Douglas Porteous and Sandra Smith defined it in their 2001 book, Domicide: the Global Destruction of Home. The project dealt with a host of issues that challenged the Chinese government’s policies and regulations. These issues include the state-sanctioned violence in urban development, intimate details of rampant corruption, persistent grassroots protests by residents, and the tension between local governments and “nail housholds,” families that refuse to relocate on government terms. Therefore, I was not surprised that Shanghai’s security apparatus took an interest in my work.

What I did not expect was the challenge in gaining access to residents’ trust. The nature of the project required broad, sustained and personal access to their private homes and intimate lives, which could not be accomplished by some well-known methods such as survey. In fact, I did not conduct any single survey or provide them with any written questions for answers.

My research centred on the following aspects: personal history; family history; community history; the history of their residence; and their experience in demolition and relocation. It was extremely important for me to learn first who they were, what their families were like, and how they came to live in their particular homes. Such information provides insight into their behaviour in their struggle against “domicide”. After all, not every resident and neighbourhood resisted or resisted in the same fashion. Their behaviour has much to do with their self-perceived identity, their values, their relationships to their homes, and their understanding of the reform. In sum, I had to know them as individuals and gain access to the details of their lives as much as possible.

Despite the fact that I am a Shanghai native, intimately familiar with the city and its culture, I did not achieve any in-depth research in the first two months of my initial fieldwork. There were a number of reasons for that. Most of the residents were traumatised by “domicide” and were in the process of mourning their loss and petitioning for their cases. They had been deceived and stonewalled by local officials and developers for years. Some of them had dealt with the media because their homes were levelled in some high profile corruption cases. But the residents did not feel that the media always accurately reported on their cases or reflected their perspectives. Some of them had also been disappointed by scholars and experts who supported their causes in public but became silent when the going got tough. In short, trust was in short supply, and they were deeply suspicious of strangers.

Also, families often have secrets that they themselves do not even want to talk about. There is a great deal of repressed memory about deaths, suicides, scandals, lawsuits, marital affairs, domestic violence, and other often painful episodes in the families. My work involved property issues, which were particularly a source of family conflict and an unpleasant and complicated topic to share with an outsider.

Moreover, many of those residents were desperate in their situation. After being evicted from their homes, some of them lived in temporary shelters, while others moved in with their parents or siblings, or rented accommodations, paying their rent they could not afford. There were also those whose homes were facing imminent demolition. They were searching for ways to save them. While they were suspicious of strangers, they also looked for outside help since their own channels were too limited to seek justice. In Chinese culture, there is a popular belief in “blue sky” officials—those upright officials who, if and when learned about people’s plight, would set things right for them. Thus, the residents looked for ways to reach out to such officials in the hope of resolving their issues.

To those residents, someone like me could be an ally to lobby for their cause, and they wanted positive results immediately or in the near future. In the initial contact, they often asked if I had any connections to government officials in Shanghai and Beijing. They also wanted to know what exactly my research was about. Would I publish my research soon? Where would my work be published, in the US or China? In Chinese or English? How long would it take for me to do the research? How could I help them? What actions should they, or we, take together? Would I go to petition with them? Later on, some of them invited me to join them on their petition trip to Beijing and offered to get me a residential identity card that was necessary for entering various petition offices.

Clearly, there was a gap between our expectations: I wanted to study their cases for a long-term project that would shed light on the larger context and issues of China’s reform era; they wanted my work to be some kind of action research so that I took action in their petitioning and appealing and helped them find solutions to their problems. This is of course a familiar challenge: who drives the research agenda?

Under the circumstances, I figured that the first step was to allow them to know me. I thought it was only fair that they should learn about me as I wanted to learn about their lives. I started with an open-ended approach to the project—while I had a general notion of what this project was about, I did not have any specific ideas about it. I applied this open-ended approach to my fieldwork. I wanted to learn everything I could about their lives and then see what emerged from the source material. This open-ended approach allowed me to see everything as relevant. In the beginning, I did not even mention that I wanted to interview them. I simply asked if I could tag along in whatever they were doing; I just spent time with them and chat with them. In this way, there was no pressure on them to tell me anything, or on me to find any “useful information.”

I went to the market with them when they did their daily morning shopping. I went with them when they were out running errands. I sat with them for hours in their neighbourhood stock market branch offices (more than 500 of them in Shanghai in 2004) as some of them were small investors and regularly spent part of their day there. I also went with them when they visited their friends and neighbours, whenever they invited me. I made sure I was not intrusive in any way, and simply listened and observed what they were saying and doing.

In the process, I was honest in sharing with them what I knew about my project and what I was discovering. I made sure they understood that it was a long-term project and that I would not write anything until years later. I emphasised the difference between journalists’ reporting on current affairs and scholars’ conducting research on such affairs. While my research was unlikely to help them in their individual, immediate causes, I did explain to them why it was important to carry out such research.

My profound respect for them also mattered. Before my field trip, I meant to study how ordinary people in urban China lived through the transition from a socialist welfare state to a market economy in the post-Mao era. As soon as my field work started, I abandoned the concept of “ordinary people” altogether, because everyone I met was extraordinary in his or her own rights. I did not and still do not feel comfortable with the term “informant” either. The term is useful and technical, but also inaccurate because people are not just passive informants.

I believe that my respect for them and their privacy was extremely important in building both boundaries and trust. I always carried my notebook, camera, and recording devices during my field research but did not take any of them out on my initial contacts with the residents. Only step by step did I ask if I could record and take note of their oral account, take pictures, visit them at their homes, talk to their family members, and look at the materials, such as petition letters, eviction notices, and court papers, they had gathered and created.

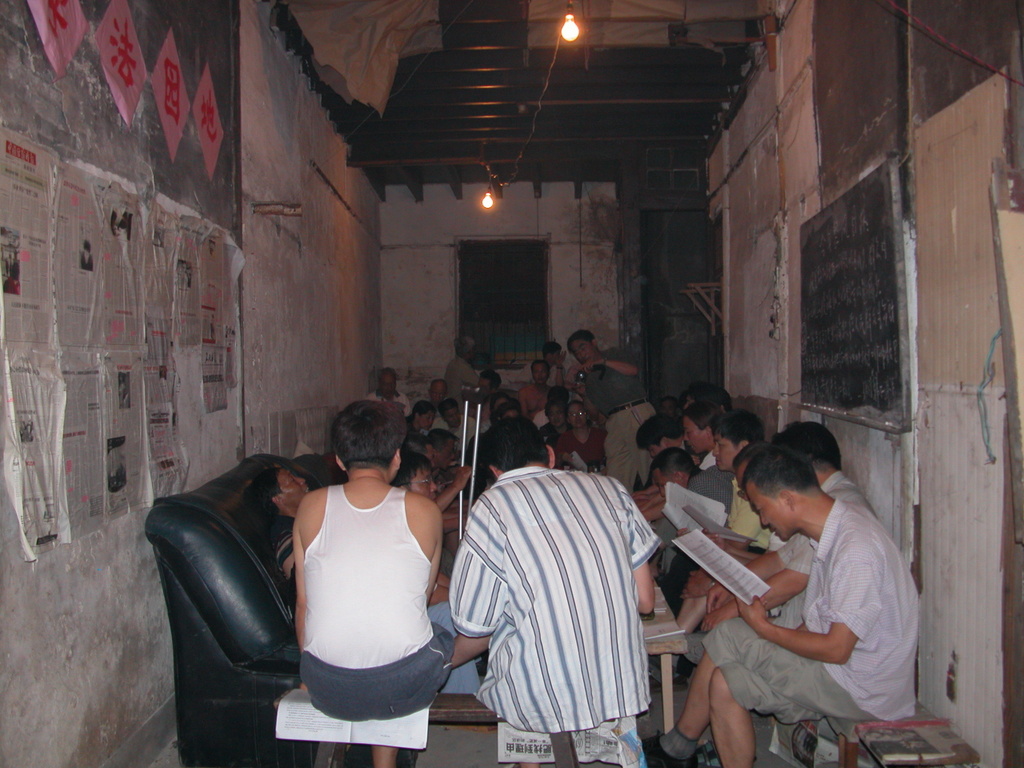

What was interesting is that as they got to know me personally, they were less obsessed about their personal issues in relation to my research. With a degree of trust, they began to open up to me. I rarely used the Chinese word for interview, “caifang,” with those residents as it seems to be too formal and distant. I simply spent countless hours in person with the residents, observing and experiencing their lives in their own environment. For instance, I was on the site of a five-hour eviction of a family. I participated in some of the residents’ meetings that strategised their resistance, got to know the entire families that I wrote about, and visited every apartment and house I studied, with exception of those that had already been demolished before my arrival.

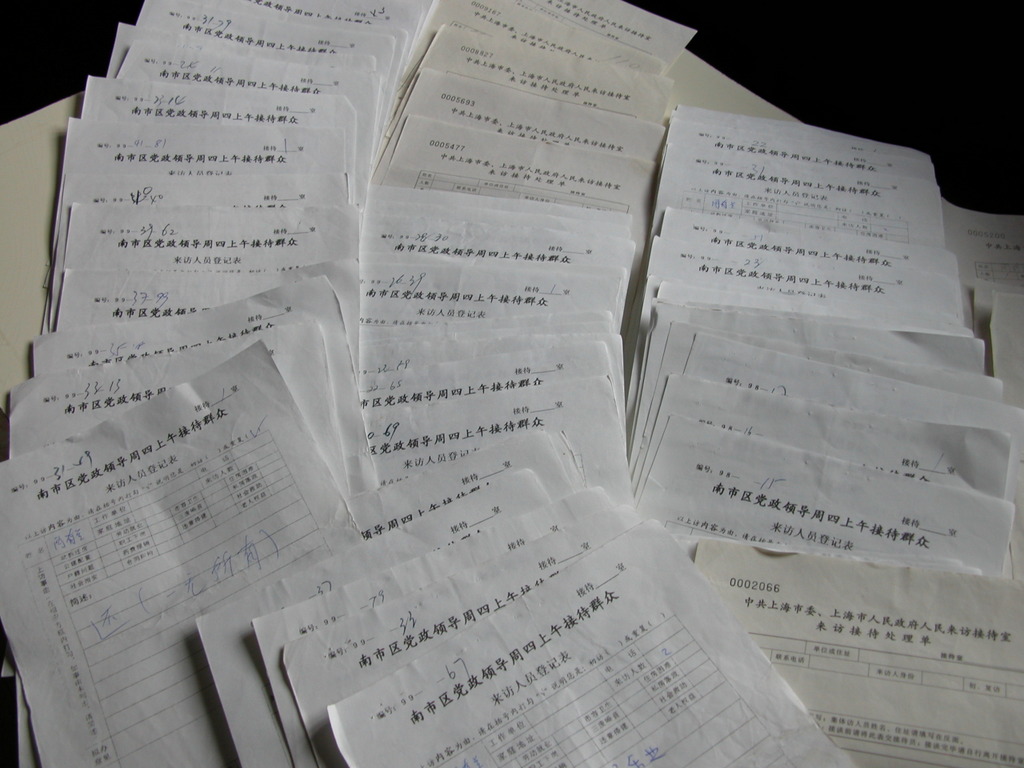

My open-ended, boundary-setting, and trust-building approach turned out to be highly rewarding. In time, I was able to gather a considerable amount of material from the residents — petition letters, court papers, family photographs, private letters, appointment papers by the Nationalist government in the 1940s, contracts, floor plans, and other documentations on their properties, some of which date back to the 1920s, as well as items they made and used in their protests. They helped me to gain access to everything that interested me. For instance, I would not have been able to enter the site of the five-hour eviction if not for a resident who told the government-assigned gate keepers that I was his cousin. In time, the residents had become so familiar with my work that they knew what material I needed and whom I should talk to.

The residents enriched my research in many ways: not only their experience made me think in new ways, but also their suggestions led to new dimensions for my project. It is in that sense that they were not just informants; they became active participants in my research. With such trust and boundaries, the residents and I drove the research agenda together.

I hope I have also contributed to their lives in some small ways by listening to their stories, sharing my views, respecting their dignity, and writing about their lives so that more people can understand them and their society. The residents and I have built a lasting friendship. At the fundamental level, field research is an interaction among human beings.

About the author

Qin Shao is Professor of History in the Department of History, the College of New Jersey since 2005. She was a Fellow-In-Residence in International Research Center on Work and Human Lifecycle in Global History, Humboldt University, Berlin between 2012 and 2013.

A Note on the Research and Results

I conducted field research and interviews for this project from 2004 to 2012, mainly in Shanghai and with Shanghai residents. This project focuses on cases from a number of districts in Shanghai, but it also uses material from other cities in China. The project was completed in spring 2013. The research has led to a number of publications as follows:

Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity. Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, pp. 326.

“Citizens versus Experts: Historic Preservation in Globalizing Shanghai.” Future Anterior, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2012 (Summer), pp. 16-31.

“Waving the Red Flag: Cultural Memory and Grass-roots Protest in Housing Disputes in China.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol. 22, No 1, 2010 (Spring), pp. 197-232.

“Bridge under Water: The Dilemma of the Chinese Petition System.” China Currents, China Research Center, Atlanta Vol. 7, No. 1, 2008 (Winter)

“A Community of the Dispersed: the Culture of Neighborhood Stock Markets in Contemporary Shanghai.” The Chinese Historical Review Vol. 14, No. 2, 2007 (Fall), pp. 212-239.

3 Comments