In this piece, Basak Tanulku shares her experiences of conducting fieldwork in gated communities in Istanbul, Turkey for her PhD research. She explains how she decided to work on gated communities, and discusses the problems arising due to difficulties in gaining access. However, access is not a linear process: rather, there are various steps and step-backs during the same study, which can have an effect on the research. Based on this perspective, Tanulku emphasises the importance of keeping a balanced relationship with the participants and of knowing how to ask the right questions.

Selecting the Topic: Gated Communities in Istanbul

I did not live in a gated community nor knew anyone who was living in one. However, I decided to work on gated communities while I was working in a university in Istanbul and collecting news published on various forms of immigration. A piece, published in Tempo Magazine titled as “The Whitest Turks Live in the North of Istanbul” (Tayman, 2004), raised interest in me about gated communities, which were described as reflections of class and cultural segregation and residents living in these developments, as symbols of “cultural whiteness”. “White Turks” has been a popular term used since the 2000s, describing people with an elite lifestyle who complain about Istanbul’s problems such as traffic, crowds and density, air pollution and lack of green spaces leading them to escape from the city centres. I reserved this news and titled it as “reverse migration” which was reminiscent of the conventional “white flight” of upper classes from city centres into suburbs, a trend seen especially in the USA and the UK. This news article brought two personal interests of mine together: a geographical/spatial concept “the north of Istanbul” and a socio-cultural one “White Turks”. Concomitantly, “gated community” is a term formed of a spatial (gated) and a social (community) concept.

Here a couple of remarks are needed on the meaning of “gated communities”: they are regarded as residential developments, containing various amenities and facilities for its residents, closed to the outside realm through various mechanisms and governed by rules and administrative teams (Tanulku, 2012; 2013). Gated communities in Turkey are analysed within the context of the emergence of neoliberal urbanism, increasing socio-spatial fragmentation, and the rise of the new middle and upper-middle classes in search for a new lifestyle, safety, community and belonging in a socio-spatially controlled environment. Istanbul, the most populated Turkish city that is regarded as the trademark and global city of the country, was the best site for me to study the subject: it is the city, where gated communities first appeared and increased in number and popularity in Turkey. Gated communities have become an important trend in the housing market and as noted by Genis (2012), while gated communities firstly targeted upper classes, at the moment almost every housing development in Istanbul is now gated, targeting various income groups.

Since my research questions were exploratory in nature that necessitated ethnographic research, I began my PhD studies in Lancaster University, Sociology Department in 2004 based on the department’s strong reputation in the areas of migration, social theory, and mobility, a good starting point to analyse gated communities from a sociological point of view. In my PhD research, I examined four main subjects: urban restructuring and gated communities’ political and social relations with other urban actors, relations between gated communities and wider urban communities, the experience of domestic space and problems arising inside housing units and gated communities overall, and the formation and perception of security and insecurity in gated communities.

Access into the Case Studies

I spent my first year at the university by reviewing the literature, taking courses and deciding what to ask to potential participants (question schedule). Working on gated communities (particularly those targeting upper classes) was challenging, since gated communities were inhabited by people with the power to exclude themselves voluntarily from the society and showing little willingness to participate in a research study, as also mentioned in the literature on upper classes (Nader, 1972) and more particularly, on gated communities (Low, 2003; Kurtulus, 2005). As discussed by Wang in the blog on conducting interviews with business elites in China, I asked my connections if they knew anyone living in a gated community. At the end, I had a list of the initial contacts, living in different gated communities in Istanbul.

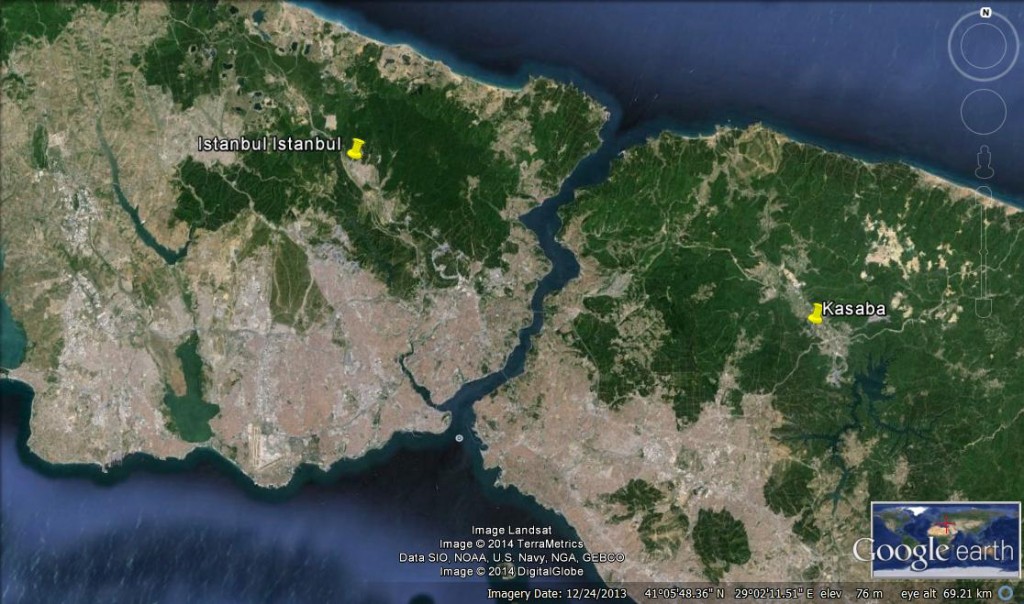

During the Easter of 2005, I started to visit the sites where I would carry on fieldwork in Istanbul and get ready for a pilot study in order to test the questions for participants. I spent the entire summer of 2005 on finding the case studies, conducting the pilot study, interviewing the professionals and the locals living in Gokturk and Omerli. However, things were not smooth for getting access into each gated community and this affected my preference for the case study I should analyse. For example, Kemer Country, the first gated community of Istanbul, known for its high-profile image, upper class residents and segregated life from the outside realm, was very difficult to conduct a fieldwork in, although I talked to two residents willing to help me to find other participants during the pilot research. When I met with the administrative staff, they did not seem helpful in allowing me to continue field research there. As mentioned previously, when the access to a site is difficult, the researcher should create alternatives (Marshall and Rossman, 1995). The ideal site of study is regarded as a place where access is possible containing a rich mix of the processes, people, progress, interaction and structures of interest. The researcher should also establish trusting relations resulting in reliable and valid data (Marshall and Rossman, 1995). For this, I visited various gated communities in different locations in Istanbul to find potential participants. However, these contacts were far from providing me with a sufficient list of contacts, while their administrative team was not helpful for granting permission to conduct a study. By getting in touch with different gatekeepers, I ended up in two case studies in opposite sides of Istanbul, accidentally built by the same developer company.

Istanbul Istanbul

My first visit to Istanbul Istanbul, the first case study, took place during the 2005 Easter vacation. The most important factor which helped me in getting access there was a person who knew one of its residents, who became my first gatekeeper. This resident directed me to the marketing director of Istanbul Istanbul as well as several residents who were working inside the community as volunteers or in administration. These people provided me with very valuable information on everyday life inside the community, the changes taking place in Gokturk and larger region, the residents’ profile, their relations with the locals living in the town of Gokturk.

During the actual field in the summer of 2006, I learned that the manager who provided a list of potential participants last year had left his job at Istanbul Istanbul. When I met with the new manager, I hesitated to tell him about the previous list, which could be understood as unethical and create pressure on him, as I would be using the source of someone else who previously worked in the same institution. I decided to carry on with the contacts provided by the new manager who helped me a lot in allowing me to visit the site.The administrative team also provided me with quantitative information on Istanbul Istanbul (i.e. how many people live, their average age, income and education level, the situation of home tenancy, the size of household, etc.). During the fieldwork, I did not have any problems while conducting interviews with residents. However, while I had full permission from the management and was very careful to provide information to all participants about the reasons of my visits to the site and conducting interviews there (Bryman, 2004), several residents in Istanbul Istanbul asked me for my actual identity card and permission letter from my department. In this case, I showed my ID and explained my motive. I completed all the interviews there in the summer of 2006. In summary, the willingness of the administrative team, my primary contacts who acted as gatekeepers and the community’s well-established status in Gokturk had an impact on the quality of the data I collected in Istanbul Istanbul.

Kasaba

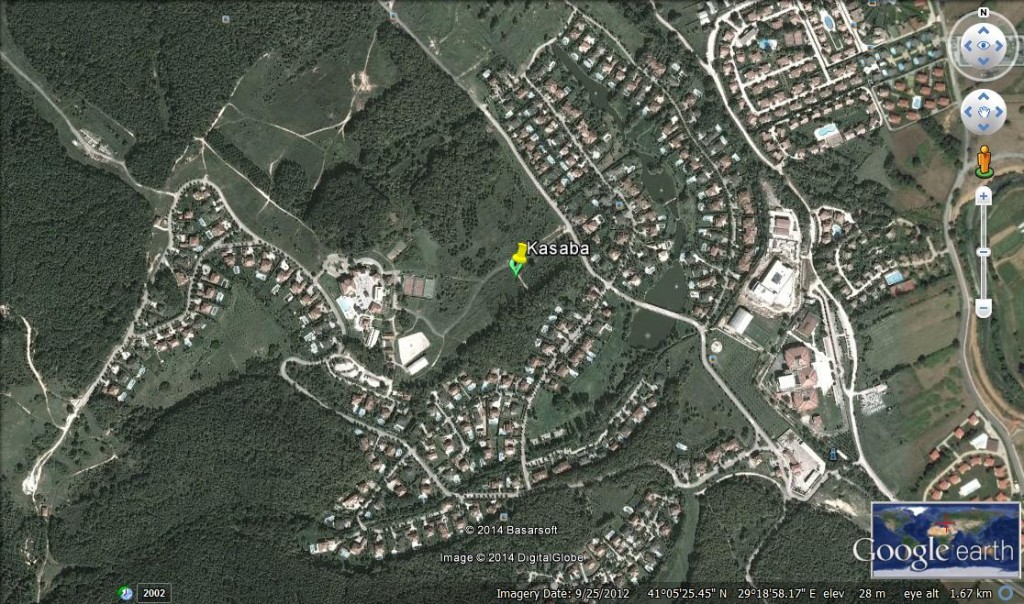

The second case study, Kasaba was very difficult to get into. It was the first community of Omerli, and had an image of an “elite” gated community, known for its high-profile residents. The most important factors which allowed me to conduct a fieldwork there was the two acquaintances of mine who introduced me to one of its residents who did an interview with me during the pilot study and introduced me to one of her friends living in Kasaba. Also the two acquaintances introduced me to a high-ranked manager of the developer company who later directed me to the administration of Kasaba in the summer of 2005. However, the manager was very reluctant regarding doing research inside the community. He told me that he did not like research projects which were considered “a nuisance” by residents.

When I re-visited Kasaba to conduct fieldwork and rekindle my connections in 2006, I saw that there was another manager who was more helpful, but the administration was still unwilling to permit a research study. I felt that they wanted to “protect” their communities from an outsider’s attack, i.e. prevent a researcher’s intrusion into the privacy of its residents. My destiny was changed when I visited the Omerli town municipality in the summer of 2006 for an appointment with its mayor. I was informed that there was a lady working in the municipality administration who was also a resident of Kasaba. It was a lucky day, as the lady who was a teacher and helpful to other previous researchers, introduced me to Kasaba and residents. She was acting as a bridge between the local people and residents in her community by arranging charitable activities in Omerli. She became my gatekeeper for Kasaba who gave me the names of several residents and/or arranged meetings with them. For example, I visited a house inside Kasaba where several female residents gathered for afternoon tea and conducted interviews with four of them. In Kasaba, I did not experience a need to prove my identity to participants, as I was directed by a gatekeeper who was also a resident there who gave sufficient trust to other residents about my identity. However, the difference between the case studies in terms of ease of gaining access continued during the fieldwork: while I did not have any difficulty to visit homes to conduct interviews in Istanbul Istanbul by myself, it was impossible for me to do the same in Kasaba. There were several private security staff members who accompanied me while I was visiting houses or even buying something to eat from its supermarket. Despite their presence during my short travels within Kasaba, the security staff did not intervene in my research while I was in a private setting and/or conducting interviews or chatting with the residents. Nevertheless, I finished my interviews in Kasaba in the summer of 2006 with a few more conducted the next year. In sum, while the lack of cooperation of the administrative team did not affect the quality of the data, it had an impact on the time I spent to collect the data.

Access as a Process: Building Trust

The continuity of a research project is dependent on building trust with participants while talking to them and keeping a good and balanced relationship with them. Conducting interviews with residents necessitates questions formulated according to their background and profession. For example, while I was talking to residents, I avoided using the term “gated community” which might restrict their freedom to answer. Instead, I asked open-ended questions by avoiding any academic language, jargon or judgmental phrase or words. Several residents who were working inside the two case study areas (either as a volunteer or an employee) provided me with valuable information and tried to advise me about my research (about which gated community I should study and what I should ask). I kept listening to them to take their advice about the research.

The residents were also free to refuse answering any question that they did not like. For instance, during the pilot study I was warned by several participants from both case study communities about the question on “average household income level”, which can be regarded as an example of invasion into the privacy of participants or involving sensitive issues (Bryman, 2004). One of them recommended me to provide income ranks, while another one advised me to remove the question as it could “bother people”. At the end, I changed the question into a more flexible format by offering them three ranks of income groups to make the participants more comfortable while disclosing their income level. While participants were unwilling to answer the first format of the question, they were more confident in answering the second format. However, despite this change, some of them still refused to answer it.

Keeping a balanced relationship with participants during a fieldwork is also a part of gaining access. As noted previously by Loubere, a researcher should know how to “play the game”, i.e. being familiar with cultural practices of participants and their everyday life and language which are important to get access into their minds and gaining their trust.In my case, residents were highly educated people who were also well-informed about the subject. In addition, most of them described their income levels as upper-middle or upper class, indicating a power imbalance in terms of income level between them and me as a female researcher who was also a student during the fieldwork. As noted by Sultana (2007), the relationship between researcher and participants is dependent on the identity of the two sides. This power imbalance was reduced by my social origin and educational background, which were similar to theirs, providing me with an easy communication with them.

Last but not least, the most important thing I was careful about during my study was to keep myself distant from the well-known criticisms of gated communities and more generally, upper-class people. This is implicit in most of the research on upper-classes, ending up judging “rich” people in order to take side of the poor,providing academics with an implicit moral reputation.For example, Shao discusses her position while she conducted a fieldwork among the evicted people in Shanghai, who demanded her to be a speaker for them in order to defend their right to housing. However, researching elites and/or upper class people needs more justification since they are the ones who are to be blamed for their high status in a society and usually do not want to be researched or exposed to the rest of society. When I was talking to residents and the professionals, I had a feeling that they thought they were doing something good by talking to me, as they were helping a student in need of help. During my field work, I adopted an objective view, as much as I could, to gain residents’ trust which allowed me to finalise my research.

References:

Bryman, A. (2004) Social Research Methods, 2nd edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press

Genis, S. (2012) “Takdim”, Ozel Sayi: Guvenlikli Siteler: Sosyo-mekansal Ayrismanin Yeni Bicimi. Idealkent May (6): 5-9

Kurtulus, H. (2005) Istanbul’da Kapali Yerlesmeler: Beykoz Konaklari Ornegi. In Kurtulus, H. (ed.) Istanbul’da Kentsel Ayrisma. Istanbul: Baglam Yayincilik

Low, S. (2003) Behind the Gates: Life, Security and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York: Routledge

Marshall, C. and Rossmann, G.B. (1995) Designing Qualitative Research, 2nd edition. SAGE Publications

Nader, L. (1972) Up The Anthropologist-Perspectives From Studying Up. In Hymes, D. (ed.) Reinventing Anthropology. N.Y. : Pantheon Books

Sultana, F. (2007) Reflexivity, Positionality and Participatory Ethics: Negotiating Fieldwork Dilemmas in International Research. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 6(3): 374-385.

Tayman, E. (2004) En Beyaz Turkler: Kuzeyliler. Tempo March

About the author

Basak Tanulku is an independent scholar from Istanbul (Turkey). Her main research areas are urban studies, socio-spatial fragmentation, gated communities and similar housing patterns, cities and consumer culture, urban and regional planning, urban transformation and more particularly, Turkish cities.

Related publications:

Tanulku, B. (2012) Gated communities: From ‘‘Self-Sufficient Towns’’ to ‘‘Active Urban Agents’’, Geoforum 43(3): 518-528

Tanulku, B (2013) Gated Communities: Ideal Packages or Processual Spaces of Conflict? Housing Studies 27(3): 937-959

For more information on the impact of gated communities on environment and urban life see Tanulku, B. (2013) Turkish Gated Communities as Spaces of Upper Class Exclusivity, Escapism, and Stigma. Retrieved from http://sustainablecitiescollective.com/basaktanulku/179331/rise-gated-communities-turkey-spaces-upper-class-exclusivity-escapism-and-stigma

For more information on the conflicts between gated communities see Tanulku, B. (2012) “Moral Capitalism” and Gated Communities: An Example of Spatio-moral Fragmentation in Istanbul. Retrieved from http://citiesmcr.wordpress.com/2012/11/27/moral-capitalism-and-gated-communities-an-example-of-spatio-moral-fragmentation-in-istanbul/

For citation: Tanulku, B. (2014) Gaining access into gated communities: Reflections from a fieldwork in Istanbul, Turkey. Field Research Method Lab at LSE (19 June 2014) Blog entry. URL: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2014/06/19/gaining-access-into-gated-communities-istanbul