This blog entry discusses the use of a ‘quasi-quantitative’ mapping method as part of comparative case-study research for a PhD, in the context of (unforeseen) constraints and scarce resources. Specifically, I present the challenges I faced working in different contexts, with different resources and in different temporal windows – and the subsequent processes of adaptation of the research design. First, I introduce the PhD research to ground the decision to use maps. Second, I discuss how a method designed for the city where I carried out my PhD (Palermo, Italy) was partially delusional in the city where I developed a second case-study (Lisbon, Portugal) and how I had to steer the research design as a consequence. Third, I reflect on the implications of a (too?) ambitious research design and summarise the lessons I have learnt with broader relevance for comparative case-study research, writes Simone Tulumello

Researching urban fear and planning practice

The main goal of my PhD research (University of Palermo; defended March 2012) was building a comprehensive, critical and exploratory theory of the relationships between urban fear, rhetoric discourses about security, the spatialities of contemporary cities and urban planning practice (see Tulumello 2017). From a planning policy perspective, the aim was to understand if, and how, fear shapes, and is shaped in turn by, planning practice, in between global security discourses and local power relationships. From a spatial perspective, I was interested in unravelling connections between (growing) feelings of urban fear and spatial transformations in neoliberal times. This post focuses on the spatial perspective.

Since 1990s, critical urban scholarship has explored how feelings of fear and rhetoric of security have intertwined with processes of restructuring of urban space, including residential fortification, socio-spatial seclusion, fortification/privatization of public space, exclusionary urban renewal and so forth. Among the theoretical concepts developed are ‘ecologies of fear’ (Davis, 1998), the geopolitics of ‘military urbanism’ (Graham, 2010) and the ‘thematisation’ of urban space (Sorkin, 1992). Such rich literature has nonetheless given limited attention to big-scale, cumulated spatial effects – as noted by Roitman et al. (2010) about works on gated communities. Scarce evidence exists, which reveals the way, and the extent to which, the summation of processes has been segmenting, polarising, fragmenting and clustering wider urban fabrics in ‘ordinary’ cities (cf. Robinson, 2011) – i.e. cities not at the core of globalising trends like Los Angeles, New York, London, Dubai or Johannesburg.

Against this background, my exploratory proposal is twofold. From a theoretical perspective, I have set out a taxonomy to emphasise the cumulative impacts of urban spatialities connected with fear, which I term ‘fearscapes’ to stress the coexistence of political-economic, social and cultural dimensions in their production (Tulumello, 2015): enclosure as spaces of exclusion/seclusion; post-public space for privatization and fortification of public space(s) and buildings; and barrier as fragmentation produced by infrastructural nets. From an empirical perspective, I decided to map the presence of fearscapes in concrete, ordinary urban territories.

Quasi-quantitative mapping with scarce resources

The methodological design I used to map fearscapes is fourfold. First, selection of the spatial entities to be included in the maps. I identified six categories, broad enough to keep flexibility to accommodate the variety of actual spatial entities:

- Enclosure: (i) spaces of compelled exclusion/seclusion and (ii) auto-secluded residential developments (typified by the gated community);

- Post-Public Space: (iii) shopping malls (which are advertised as the ‘new’ public spaces), (iv) privatised public spaces/buildings and (v) fortified public spaces/buildings;

- Barrier: (vi) infrastructural networks (roads and railways) that impede mobility in the direction transverse to their longitudinal route.

Second, I use the expression ‘quasi-quantitative’ mapping to emphasise that: on the one hand, I needed to ensure that almost all the spatial entities under each category would be identified; and, on the other, missing a few of the expected dozens (if not hundreds) of spatial entities would not have compromised the comprehension of overall spatial effects. It was soon clear that the only way to systematically map some of the aforementioned spatial entities was to verify whether each dwelling, public space or infrastructure in the territory of study should have been included or not.

Third, selection of the territorial unit of analysis. I judged the municipality big enough to explore different morphological, historical and topographic contexts, and not too big to entail too much work for an individual researcher – this was an estimate of available resources for the first case-study.

Fourth, I selected Palermo, the city where I was carrying on the PhD, as the first case-study. Palermo is a middle-sized city in a context, Southern Italy, at the margins of globalising transformations, still experiencing late neoliberal trends – an ‘ordinary’ urban context. The municipality covers a territory of 160 km2.

In Palermo I could make use of three kinds of ‘resources’. First, web-based, free-access GIS (Google Earth, Google Maps, Google Street View and Bing Maps), which offers aerial, street and bird’s eye views, allowing me, e.g., to determine in most cases whether a residential development is fenced and the access filtered by security posts. Second, a motorbike, perfect private transport means for on-site visits, which were necessary to produce photographic documentation and verify dubious cases. Visits were decisive for some categories – e.g. the privatisation/fortification of public spaces needed to be systematically verified on-site. Third, my in-depth knowledge of the territory, as well as of the political and social history, of the city where I had been living almost all my life. For instance, the fact that some buildings, refurbished with public funds to be public services, are managed as for-profit bars may have remained unknown to a ‘visiting’ researcher.

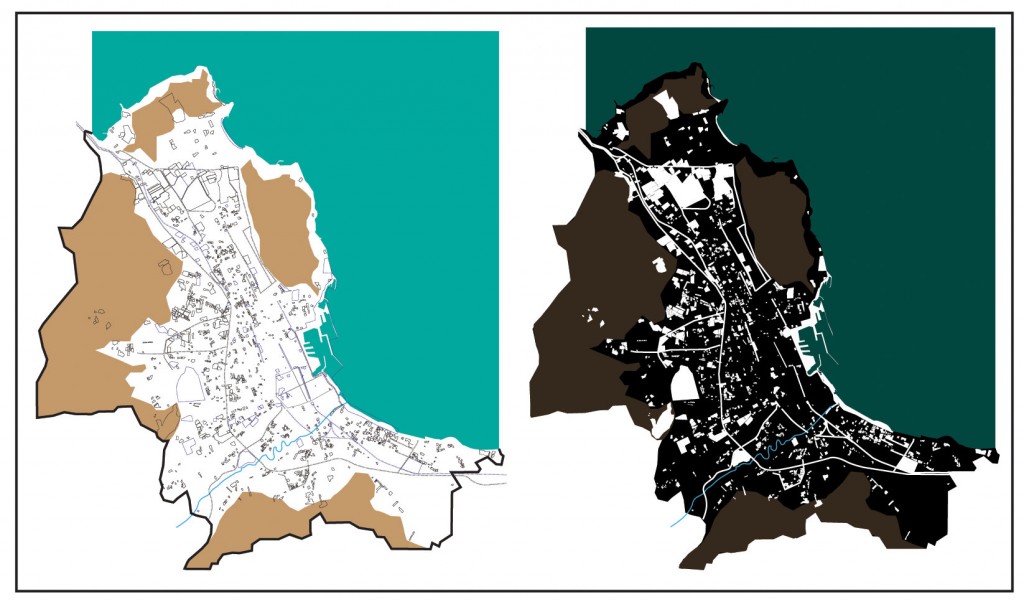

The estimate of feasibility was correct. I completed the maps in about nine months (July 2010 to March 2011, plus some further visits between December 2011 and February 2012). During those months I carried out further empiric research, i.e. data gathering for the planning policy perspective (interviews, policy analysis, analysis of media production). In addition to desk work on GIS and graphic software, about ten day-long visits were necessary. The data gathering was satisfactory, with findings subsequently published in a refereed journal (Tulumello, 2015). To give an idea of the overall operation (see Figure 1), I mapped around 1,200 walled residential developments, two spaces of compelled exclusion/seclusion, 20 shopping malls and similar facilities, nine privatised public spaces/buildings, 55 fortified public spaces/buildings and 30 infrastructures.

The opportunity to carry out a second case-study materialised at the beginning of the third year of the PhD, after having secured a scholarship for a six-months visit to Lisbon (April to October 2011). Lisbon, having experienced late neoliberal trends since the 1990s, was a perfect case for comparison, allowing me to widen the empirical focus to Southern Europe. Lisbon municipality is extended over 80 km2.

Once in Lisbon, it was soon clear that I would find it hard to fulfill the mapping with the same accuracy as in Palermo. First, in absence of private transport means, I had to rely on slower public transportation. Second, I knew Lisbon superficially, without in-depth knowledge of political and social processes. And, third, I squeezed the empirical research in six months. As a result, I could not carry out all the on-site visits I deemed necessary for the maps. This was partially balanced by the existence of secondary sources not available in Palermo – e.g. previous research on condomínios fechados (Portuguese gated communities). At the end of the visiting period, I had to admit that the mapping could not be considered complete for the following categories:

- Secluded residential developments – most condomínios fechados are not walled (CCTVs and 24/7 patrol are used) and I should have visited more developments than those I could;

- Privatised public spaces/buildings – I might have missed cases similar to the public building turned bars in Palermo;

- Fortified public spaces/buildings – I might have missed several cases because of the impossibility to carry out all the surveys I deemed necessary

The comparative study was unbalanced. While ‘replication’ (cf. Yin, 2003 [1994], 47) was rigorous for the case-studies in the planning policy perspective of the research – e.g. the exploration of the role of fear in the planning histories of two council housing districts (see Tulumello, 2017, chapter 5) – no rigorous comparison of the maps was possible. As such, rather than uncovering convergent/divergent patterns in the two contexts, I employed evidence from maps to exemplify/explore the theoretical framework (see Tulumello, 2017, chapter 4). I used the maps I deemed rigorous enough to reconsider the taxonomy produced on the grounds of existing literature – that is, adding nuances to and problematising the theory rather than reinforcing it through replication.

(Scarce) resources, ambitions and context in case-study research

A PhD can be considered an (often ambitious) research project carried out with scarce and uncertain resources. Often, no research funds are available, and funds for research missions are found (if they are found) during the development of the project. As such, three dimensions are crucial for the possibility to carry out qualitative and ‘quasi-quantitative’ empirical methods: the personal availability of practical resources; the contexts where the research is carried out (including the personal knowledge of them); and time constraints, especially for research in multiple locations. At the same time, a PhD is a formative experience and the balance ambition/feasibility is often grounded on estimative attempts at preventively ‘measuring’ the efforts to be needed for empirical activities – at least in my case, it was.

The easy solution would have been designing a less ambitious research project. Still, I am happy for having been more (too?) ambitious and then having had to adapt to new possibilities and some delusions. Reflexively thinking about this experience, I believe that coping with the dichotomy of new opportunities versus (unforeseen) constraints has been an important pedagogic process. The main lesson I have learned is the possibility to re-frame the research design (both empirically and theoretically) to accommodate new opportunities (e.g. adding a case-study) and unforeseen constraints (e.g. different resources available for different cases).

This, in my opinion, has wider implications linked with the very nature of case-study research. At the end of the day, we need to accept that comparative case-study research does not work as the exact replication of a same ‘experiment’ over different ‘objects’ of study. On the contrary, it should work as/through the production of ‘thick narratives’ (cf. Flyvbjerg, 2006): if we adopt a reflexive approach and start considering the context (including resources and constraints) as a ‘subject’, we can learn to adapt research design on-the-job following the hints provided by the material we gather – and still produce rigorous and impactful evidence in the process.

Reference:

Davis, M. (1998) Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster. NY: Metropolitan Books

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2): 219-245

Graham, S. (2010) Cities under Siege: The New Military Urbanism. NY: Verso

Robinson, J. (2011) Cities in a World of Cities: The Comparative Gesture. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35(1): 1-23

Roitman, S., Webster, C. and Landman, K. (2010) Methodological Frameworks and Interdisciplinary Research on Gated Communities. International Planning Studies 15(1): 3-23

Sorkin, M. (Ed.). (1992) Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of the Public Space. NY: Hill & Wang.

Tulumello, S. (2015) From ‘Spaces of Fear’ to ‘Fearscapes’: Mapping for Re-framing Theories about the Spatialization of Fear in Urban Space. Space and Culture 18(3): 257-272.

Tulumello, S. (2017) Fear, Space and Urban Planning. A Critical Perspective from Southern Europe. Cham: Springer.

Yin, R. (2003 [1994]) Case Study Research. Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

About the author: Simone Tulumello

Simone Tulumello is Post-doc Research Fellow (Planning and Geography) at the University of Lisbon, Institute of Social Sciences. His research interests lie at the border between planning research and critical urban studies: urban security and safety; power and politics in planning; futures studies, ICTs and territorial governance; neoliberal urban trends; crisis and austerity in Southern European cities. Simone can be reached via e-mail and twitter.

1 Comments