By Nicola Cortinovis (left) and Frank van Oort (right), Erasmus University Rotterdam

By Nicola Cortinovis (left) and Frank van Oort (right), Erasmus University Rotterdam

Knowledge and technology can spill over from multinational enterprises (MNEs) to local firms through channels other than buyer-supplier relations, write Nicola Cortinovis and Frank van Oort. The analysis shows that industrial relatedness (e.g. in terms of technologies and skills) between industries conveys spillover effects from MNEs, resulting in higher employment levels in local industries.

The literatures in economics, economic geography and international business argue that hosting multinationals (MNEs) may have a beneficial impact on domestic firms, for example in terms of innovation and productivity. The main explanation lays in the advanced knowledge and technologies developed and spread by MNEs to their foreign affiliates, which – under certain conditions – spill over to local firms in the hosting economies [1]. Theoretical arguments and empirical evidence indicate the prevalence of between-industry spillovers thanks to the input-output (I-O) relations linking foreign and local firms [2].

In this column, we take a more encompassing perspective on spillovers, arguing that I-O linkages are only one of the channels through which these effects may occur. Labour mobility, similarity in the technologies used and inter-firm collaborations are other possible channels – not captured by I-O linkages – for knowledge exchanges between domestic firms and MNEs. More specifically, we argue that firms may learn from each other even when operating in sectors separated in terms of I-O relations, but similar in terms of knowledge, skills and technologies. We test these ideas using the concept of relatedness to capture such between-industry similarities [3]. Our study focuses on the effect of MNEs on employment in European (NUTS2) regions both for conceptual (knowledge intensive industries and relatedness are generally associated with employment opportunities) and for policy reasons (employment effects of MNEs in a context of economic crisis).

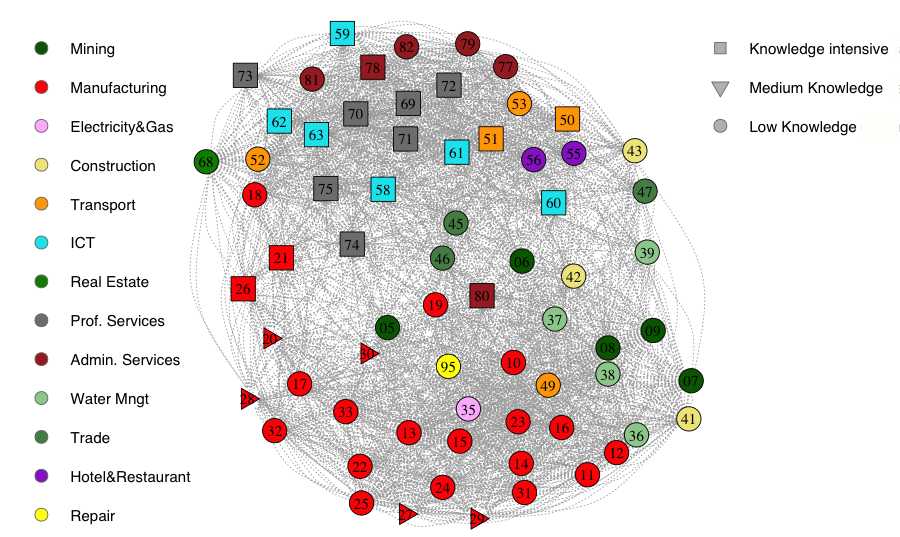

For each European region between 2008-2013, we look at the employment levels of 68 industries and the number of MNEs located in the same industry and related industries. The idea behind this method is that, if specialisation in sector A systematically occurs with specialisation in sector B, industries A and B are likely to share similar inputs, skills or technologies, thus being related. As higher relatedness indicates greater chances for knowledge in sector A to find application in sector B, we theorise that relatedness to MNE-hosting industries [4] (e.g. in sector B) would induce spillover effects in other industries (in sector A), thereby leading to higher employment.

Figure 1 shows the network representation of relatedness between the 68 NACE sectors we collected data for. The shape and the colour of each node vary according to the sector and its knowledge intensity. Rather interestingly, knowledge intensive industries (square nodes) sorted themselves in the upper part of the graph: this suggests that knowledge intensive industries tend to be more closely related with each other than with medium- and lower-knowledge intensive sectors. Whereas the graph highlights the split between knowledge- and service-oriented economies and less knowledge intensive and more manufacturing-focused ones, it also suggests relatedness captures more than simple value chain linkages. For instance, production of computers and high-tech equipment (node 26) and the manufacturing of basic chemicals (20) and pharmaceutical products (21) appear as rather closely related – though not necessarily through I-O linkages. Similarly, ICT programming and consultancy (nodes 62 and 63) are closely related to each other as well as to research and marketing (73) and management consultancy (70).

Our results indicate that the presence of MNEs is associated with higher employment levels, both within the same industry and across related industries. However, positive effects of MNEs on domestic employment are contingent upon the modelling of both regional and industrial heterogeneity. In particular, the effects are stronger and more significant in knowledge intensive sectors and in less advanced (Eastern European) regions of Europe. From these results, we derived two main conclusions. On the one hand, industrial relatedness suitably captures MNE spillovers and can thus offer a complementary tool for modelling the relations between foreign and domestic firms. On the other hand, our results offer some insights on the employment effects of MNEs: unlike what the public opinion usually perceives, hosting MNEs have a beneficial impact on local employment. Including schemes for attracting and embedding multinationals in the local economy within the regional development strategies may help unlock growth in lagging areas of Europe [5].

This post is based on the Working Paper titled “Multinational enterprises, industrial relatedness and employment in European regions” by Nicola Cortinovis (EUR), Riccardo Crescenzi (LSE), and Frank van Oort (EUR). It represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.

Nicola Cortinovis is an Assistant Professor of Regional and Industrial Economics at the department of Applied Economics of the Erasmus School of Economics.

Frank van Oort is a Professor of Urban and Regional Economics at the Erasmus School of Economics and Academic Director at the Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS).