Kirk Bansak, Jens Hainmueller and Dominik Hangartner’s study of the European refugee crisis shows broad support across Europe for the proportional allocation of asylum seekers.

Scenes from the front lines of Europe’s refugee crisis depict a border overwhelmed by the influx of desperate people on the move. The Italian Coast Guard operates at full tilt to rescue boatloads of migrants at sea; in Greece, sprawling refugee camps housing tens of thousands have stretched the country to its limits. Local institutions are buckling under a backlog of asylum applications, leaving many asylum seekers in limbo.

Europe’s asylum system wasn’t built to withstand circumstances like this—when not only the Syrian civil war but many entrenched conflicts across Africa and the Middle East will continue sending people fleeing toward Europe for the foreseeable future. Under the current Dublin Regulation, the EU member state where an asylum seeker first arrived is responsible for the application. Since the refugee crisis hit, many have argued that the Dublin status quo is not only logistically unsound but also inherently unfair, given that most asylum seekers today will come through the southern border countries. A campaign to reform the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) has picked up steam over the past year, with proponents calling for greater solidarity and a fairer sharing of responsibility for refugees.

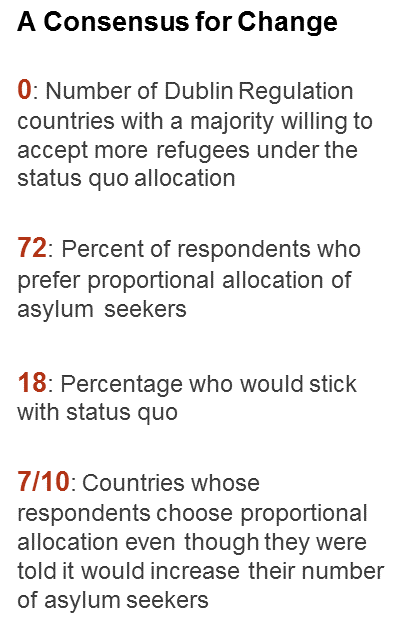

While EU leaders hammer out reforms, however, they seldom hear the voices of ordinary Europeans debating the issue in pubs and cafes. What kind of asylum system do they want? We conducted an unprecedented survey of 18,000 Europeans in 15 countries to find out, and the answer was clear: Europeans would strongly prefer a system that allocated asylum seekers in proportion to each country’s capacity—even if that system brought larger numbers into their own country.

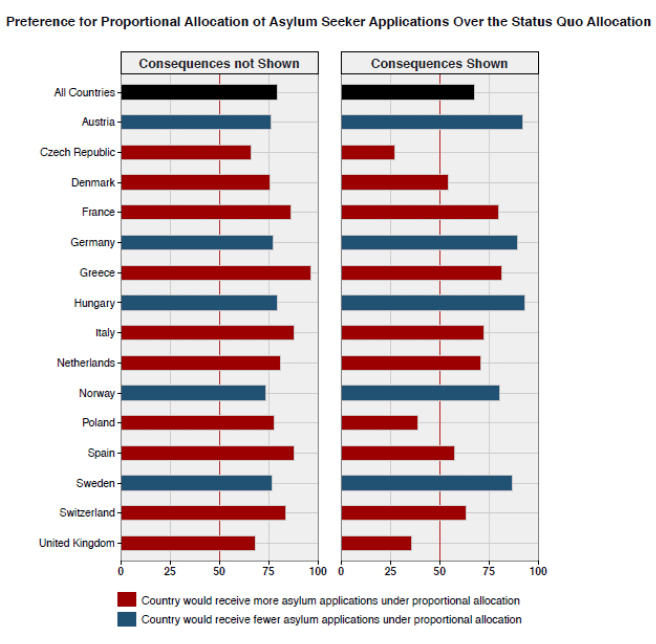

Given the high costs and social unrest that some countries have experienced while accommodating large numbers of refugees, one might think plenty of Europeans would want their own country’s share to be as low as possible. Most countries would see an increase if the EU moved to a proportional allocation system, which would take into account each country’s population, GDP, unemployment rate, and the number of applications already received. Yet the principle of proportional equality appears to be deeply ingrained in the public’s understanding of fairness in the world. With the two impulses in tension, are people more likely to ask whether the asylum policy benefits their own country, or whether it is designed to be fair for everyone?

We randomly assigned manipulations to see which holds sway. When respondents were informed of the options presented—the status quo, proportional allocation, and an equal number of asylum seekers for each country— majority support for proportional equality remained nearly unchanged. This suggests that the norm is so widely shared, and so intuitive, that it doesn’t need to be explained. And when respondents were told how many asylum seekers each option would send to their country, allowing them to easily pick the one with the lowest number, proportional allocation saw decreased support in most countries but still won a 56% majority. This preference was remarkably consistent across the surveyed countries, including major EU powers and new members, border and interior countries, and ones with few and many asylum seekers. It persisted, too, among respondents on the left, right, and centre of the political spectrum.

In the years since the crisis hit, the world has looked on the scale of the human tragedy and called on European countries to work together to protect and provide for the refugees. Our study shows that there’s strong desire for cooperation and coordination, but that desire is thwarted by the Dublin Regulation system. Beyond the refugee crisis, this shows that voters care about how international institutions are designed, not just about the results they deliver for individual countries. European leaders may worry that any increase in asylum seekers brings the risk of public backlash and a loss of political position. But these results point to a consensus broad and strong enough to empower them to move confidently toward reforming the system.

Taken from: Kirk Bansak, Jens Hainmueller, Dominik Hangartner (2017): Europeans Would Support a Proportional Allocation of Asylum Seekers, Nature Human Behaviour, forthcoming.

Image credit: European Parliament

Kirk Bansak is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Stanford University and a Graduate Affiliate of the Immigration Policy Lab with branches at Stanford University and at ETH Zurich.

Kirk Bansak is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Stanford University and a Graduate Affiliate of the Immigration Policy Lab with branches at Stanford University and at ETH Zurich.

Jens Hainmueller is a Professor in the Department of Political Scienceat Stanford University and holds a courtesy appointment in the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Jens Hainmueller is a Professor in the Department of Political Scienceat Stanford University and holds a courtesy appointment in the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Dominik Hangartner is Associate Professor in the Department of Government at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Faculty Co-Director of the Immigration Policy Lab with branches at Stanford University and at ETH Zurich.

Dominik Hangartner is Associate Professor in the Department of Government at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Faculty Co-Director of the Immigration Policy Lab with branches at Stanford University and at ETH Zurich.

Note: this article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.