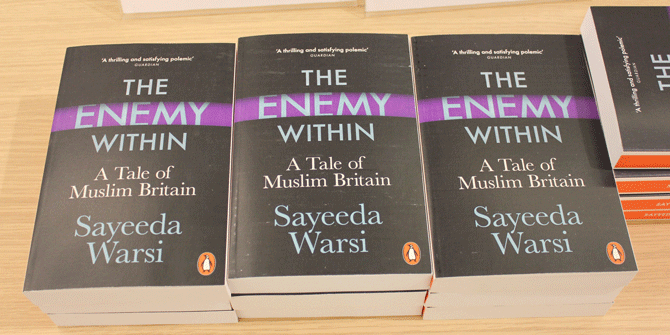

Dariha Choudhry reflects on our event with Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, who discussed her new book ‘The Enemy Within: A Tale of Muslim Britain’ at LSE on Thursday 8 March 2018.

Churchill or Britain’s Christian Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Obama or America’s first African origin President Barack Obama, Baroness Warsi or Britain’s first Muslim woman to serve in the British cabinet? It is no surprise that modern day narrative includes the minorities’ ancestral ethnicity and religion when referring to an individual’s achievements in the public or private realm, but has no such mention when it is someone whose appearance fits the stereotypical majority.

I attended the event “The Enemy Within: tale of Muslim Britain” held on 8th March at LSE with guest speaker Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, who is a lawyer, politician and ex-member of British cabinet and also happens to be of Pakistani ancestry, grew up in Britain and became the first Muslim woman to serve in the cabinet. It was thought provoking to hear Sayeeda Warsi speak about the challenges she faced, her transition from being an outsider to an insider as part of the cabinet and her definition of “Muslim Britain.”

“Muslim Britain” may seem an alien term to many people. Why would one refer to Europe’s hub as Muslim? However, statistically the Muslim population is larger than all the other non-Christian faith groups put together in Britain. During the talk and question and answers session Baroness Warsi said that there are many policies within Government circles that need revisiting and it is not possible to progress without addressing “Islamophobia” or the misconception that Islam is a threat to the identity of Britain itself.

As a “Muslim Pakistani girl” studying abroad and living on her own, the idea of the west in correlation to Islam is of particular interest to me due to the stereotypes I face on a daily basis. I have been asked multiple times if I am allowed to go out for a meal as per my will when in Pakistan, or why am I not covering my head, or am I allowed to dine at restaurants where alcohol is being served? Moreover, over the last year in London, many people have asked how I was allowed to study and live abroad on my own despite being Muslim? I have also been asked if I will accept my husband marrying three other women? While it would be false to claim that no one faces such restrictions and challenges even today, it is equally false to claim that this is the only practice. A glance at the audience itself in the Wolfson Theatre on a rainy Wednesday evening at LSE was enough to dismiss these stereotypes and misconceptions. No girl present in that lecture theatre would be marrying a man who will marry three other women and no man in that room is looking for more than one partner to marry. Rather than frustration, I feel surprised by the ignorance that prevails despite the easy access to information in today’s globalised world. Originating from Pakistan, we have not grown up to be ignorant of the west, and I believe that is due to the impact Western policy has on Pakistan itself, which in turn affects citizens on a daily basis.

Baroness Warsi herself drew attention when she turned up at 10 Downing Street in a traditional shalwar kameez. News headlines focused on her Asian traditional attire, rather than her qualifications. The most striking comment for me made by the Baroness Warsi during her talk was that people often speak about ‘immigrants’ or ‘settlers’, but who did not immigrate to the UK? Perhaps some families did a few hundred years before others, but they did regardless. They are all immigrants. They are all settlers. How many generations need to have lived in a land before they are wholly accepted as being a part of it?

Muslims have contributed immensely towards building Britain. Whether one goes back to the colonial times and how Britain extracted resources from many Muslim lands: resources in terms of skills, labour and capital, or whether one looks at the contribution to Britain’s economy by British Muslims today. A substantial percentage of the skilled labour force is comprised of “Muslim British.” During her tenure as a cabinet member, Baroness Warsi introduced Islamic finance policy, something that also played a part in giving life to one of London’s most iconic buildings – the Shard. Hence, referring to “Muslim Britain” is necessary as a dialogue that helps counter misconceptions and stereotypes. This is what Baroness Warsi herself is advocating for and is the message carried in her book “The Enemy Within – a tale of Muslim Britain.”

Another interesting point that was raised during the Q&A session was how people’s sentiments have changed over time. While traditional Britain felt more tolerant and welcoming of the ‘immigrants,’ recent events have led many ‘settlers’ to reconsider returning to their ancestral roots and considering moving back to their so called “home-country,” one to which many like Baroness Warsi herself have little association with except for a visit to their grandparents or a holiday to attend a relative’s wedding.

Leaving the Wolfson Theatre, I could not agree more with Sayeeda Warsi that “Muslim Britain” is an idea that needs to be addressed. However, it should be spoken about such that no man or woman should feel less or more British because of his or her ethnicity. In a multi-diverse country, there will never be a single voice and hence “we must let a thousand flowers bloom.”

Dariha Choudhry is currently pursuing her Masters in Political Science and Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Previously, she has received her BSc (Hon) in Political Science and Economics from the Lahore University of Management Sciences. Her research interests lie in the electoral process, developmental projects and their subsequent policies, and the role of geo-strategic location in defining international relations.

Dariha Choudhry is currently pursuing her Masters in Political Science and Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Previously, she has received her BSc (Hon) in Political Science and Economics from the Lahore University of Management Sciences. Her research interests lie in the electoral process, developmental projects and their subsequent policies, and the role of geo-strategic location in defining international relations.

Twitter: @DarihaAmbreen

Note: this article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.