Think tanks work best when they assume the role of a boundary worker between policy-makers and academics, writes Enrique Mendizabal, who illustrates the challenges that think tanks across the globe face in convincing academics that a collaborative relationship could improve their impact.

Think tanks work best when they assume the role of a boundary worker between policy-makers and academics, writes Enrique Mendizabal, who illustrates the challenges that think tanks across the globe face in convincing academics that a collaborative relationship could improve their impact.

Think tanks in developing countries have recently found themselves near the top of the aid agenda. Old and new funders are rediscovering the transformative potential these organisations can have on both policy and politics in developing countries. The success of the Chilean democracy – which is today being tested by what is an educated and politically mature young middle class – is testament of the power of think tanks.

But it is not just in the political circles of the developing world that think tanks are playing a noticeable role. In the UK, and across the West, think-tanks preserve their great influence on government policy-making. Some of this is due to their ability to rapidly disseminate evidence-based research while some are being asked uncomfortable questions of their funding sources, and therefore the independence of their research. Either for good or not, the influence such organisations hold over national policy-making is undeniable.

Looking to Chile

Think tanks have grown across the globe to fill a number of institutional gaps. In Chile, think tanks emerged as a solution to the sudden shut down of research departments in Universities by the Pinochet regime and provided safe houses for scholars and their ideas. In Peru, on the other hand, they emerged as a vehicle for poorly paid academics to make an extra income; and in many African countries they are seen as a solution to the critical research capacity shortfall that still prevails.

Over the years, these think tanks in Chile moved from soul-searching research to more proactive participation in the efforts to reinstate democratic institutions. In time, they were joined by some of the country’s political intellectuals and became the hosts of public meets, debates, and research programmes that were to become the basis on the Concertación government that took office in the 1990s after democracy was reinstated in Chile.

Much like think tanks and academic institutions across the world, Chilean universities had benefited from constant support from funders such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, as well as European political foundations. Canada’s International Development Research Center (IDRC) has also played a consistent role in funding academic thought across the region. This contributed to the development of what was, in essence, an enviable cadre of politically aware academic scholars and public intellectuals. In the long run, too, their sustainability depends on the continuous existence of a strong tertiary education sector.

Relationships with the state

Think tanks are best defined by the positions they adopt in the social space and their relations to other players: political and policymaking bodies, academic institutions, the media, organised civil society, funding agencies, and the private sector. Different associations account for a great deal of the functional and organisational differences that are possible to observe across think tanks: in Japan they are closely associated to the corporate sector, in Germany to the State and political foundations, in Zambia to international funding agencies and NGOs, in the UK to political parties, and so on.

Donors want results and are rather inpatient of academic timelines. Think tanks offer a more attractive prospect: shorter and quicker policy analysis and the explicit commitment to influence policy. It is also more direct and easier to manage, as these are often independent organisations with few formal links to complex bureaucratic or academic structures. But funding to think tanks in countries where academic research capacity is week or non-existent can have rather serious and negative effects on the success and sustainability of the outreach itself.

While these new funds may help pay for attractive pay packages that guarantee a highly qualified workforce, in developing countries this is often secured at the expense of universities and even policymaking bodies. Without competent lecturers and professors, universities will inevitably default on their duty to nurture new generations of researchers; thus contributing to what is an already limited and highly expensive labour force.

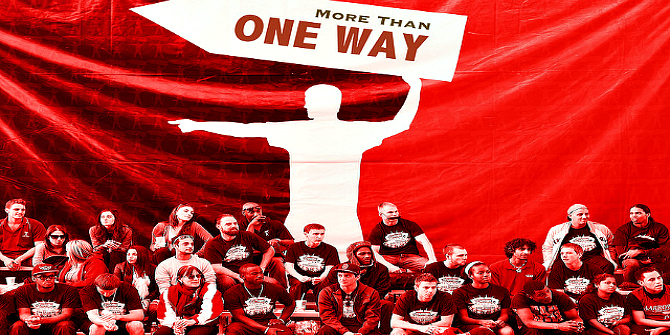

Furthermore, besides running out of people, these think tanks will also run out of ideas. Think tanks are at their best when they operate as boundary workers between the policy, academic, mediatic, and business communities. In this role they provide an invaluable service but are dependent on the capacity of others.

They add value by translating specific studies into policy arguments, transforming ideas into technologies, or creating and taking advantage of windows of opportunities to bring problems and solutions together.

Academics and policymakers need think tanks, too. Without them, they would have to, if evidence were to play any role in policymaking, bring their diametrically different work cultures and timeframes together. Think tanks broker between them: they allow academic researchers to work over longer timeframes without having to worry about keeping close watch on opportunity windows and on going commentary; and offer policymakers with timely advice and support as and when they need it.

This requires, in my view, a collaborative relationship that some funding instruments can sometimes undermine. Demanding ‘impact’ from universities, for instance, significantly limits their willingness to work through others. And, in some cases, drives think tanks and academic departments to bid against each other.

Collaboration must take into account ways to increase the opportunities for people and ideas to flow more easily between them. This may include:

- Hosting think tanks within University campuses

- Offering spaces for meetings and conferences

- Providing internships for undergraduate and graduate students

- Facilitating or encouraging applications of think tank staff for graduate programmes or particularly post-doctoral degrees

- Establishing collaborative research programmes where universities focus on long-term research while think tanks pay greater attention to shorter-term policy debate and commentary

2 Comments