Clever book titles or pretty cover designs which don’t give much away are best left to star writers whose name is enough to sell the text. For the rest of us, advice from a good editor can be beneficial. Pat Thomson looks at just how much those little things really do matter if books are to have an impact amongst readers.

Clever book titles or pretty cover designs which don’t give much away are best left to star writers whose name is enough to sell the text. For the rest of us, advice from a good editor can be beneficial. Pat Thomson looks at just how much those little things really do matter if books are to have an impact amongst readers.

One of the things that academic authors get very vexed about is the title of their book. They also often get very concerned about what goes on the cover. I’m no exception to this, although I have learnt to be a bit more sanguine about it. This is largely because I have discovered that I can get these things wrong and I don’t always know best.So here goes the confessional. I’ll start with a minor mistake about author order – something that neither the publisher, marketing staff nor I considered at the time. A while ago, I co-edited two handbooks for doctoral researchers. My co-editor and I decided to alternate the order of names so that she would be first editor on one, and I would be first on the other. Democratic and a fair distribution of attributions, we thought. The design team developed covers and spines that would fit together so it would symbolically be clear that the books were a pair. They could be bought singly of course, but they were designed to be put together. What we hadn’t considered was that in university bookshops, and in bookshops catering for university students, the books were often filed alphabetically.

This meant that, rather than being seen as a pair – one for supervisors and one for students – the texts were quite often put as separate titles on separate shelves. They were half a set – see above and below.Whether this ultimately affected sales isn’t really clear, but it was an interesting thing for all of us to think about!

Here’s my second example – and it’s one about titles and covers.

A while ago I wrote a book about headteachers’ work. As a former headteacher, this is something I not only know a bit about, but it’s also something I care about. When I arrived in England from Australia I was pretty outraged by the way in which I saw headteachers being named and shamed and also feted and rewarded. Well of course there is a longer argument attached to why I felt so strongly about this and I decided I’d better write about it. It took me a long time to get the material for the book together and I was pretty happy with it when I’d finished. The title of the book that I’d initially suggested to the publisher was simply Heads on the block, but this ended up being the strap line, with the final title being School leadership – heads on the block?

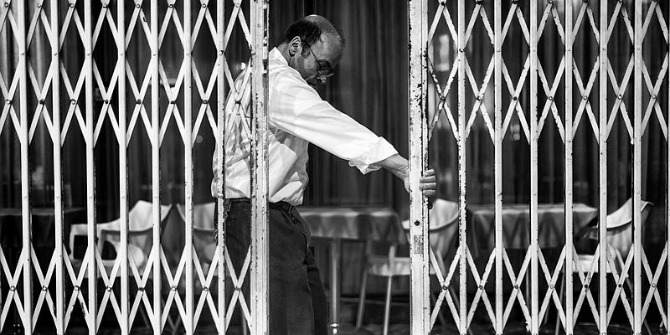

I was particularly concerned about the cover for the book and after much to-ing and fro-ing between the designers, the publisher and me, we decided on a pretty graphic picture of a head-like chap slumped against a wall looking very stressed. I loved it then. And I still love it even now. What a contrast to all those triumphal books about leadership I thought, and doesn’t everyone who’s actually done the job know that there are lots of times just like this?

Well, the book has been a bit of a publisher’s problem child. Heads don’t want to read about hard times, they have enough of them – although heads weren’t actually the target market. But it turns out that people who teach and research leadership largely recommend and buy the triumphal books. That’s why there’s so many of them and they keep being written. Buyers just weren’t attracted in great numbers to either the title or the cover – both of which aptly represented the argument made in the book. It was actually the nature of the book rather than its title or cover which were the issue. However this might have been less obvious had we chosen a less graphic title and cover. (As compensation, the book has been well reviewed and has won a little award as well, so it isn’t all bad news. And my publisher has been at great pains to tell me that these things happen and it’s not my fault. But it was a lesson.)

Clever titles which don’t give much away can be used by academic star writers whose name alone is enough to sell their books. For the rest of us, the clever bits are at best left for strap lines. In reality and not because of the heads on the block example, I’m OK with the publisher taking the running with the title of the book. Publishers care a lot about titles because they do have a direct impact on sales and on readership. Straightforward titles that give a pretty good indication of the contents are likely to come high up in searches of online book depositories and in academic data-bases. They are likely to appear ‘safe bets’ to those browsing catalogues – people such as university librarians. (And it is still university libraries which are the basis of most academic book markets.)

Nearly all of the books with which I’ve been involved have titles which aren’t entirely mine. The marketing team has a big say in these, it’s not just the commissioning publisher or editor, and the conversation about titles often happens at the point where there is a decision being made about whether to offer a contract or not. My experience is that it is not at all uncommon for a contract to be offered with a different title than the one submitted on the proposal. Now of course there is room for manoeuvre over this, but ultimately the final title will end up being something that the company believes it can market and sell. That seems fair enough to me. Publishers know the book trade and I know my academic field and there is an overlap in the middle where we put our collective know-how together.

Publishers generally seem to think that book covers are not nearly so important as titles. Like many authors I’ve therefore been able to have a real say about book covers – in some instances I’ve actually supplied the photographs or concepts which have been used. For instance I came up with the idea for the cover of the latest book on writing journal articles. It’s not brill but what matters is that it’s inoffensive.

Inoffensive matters a lot because there is one book where I and my co-author had no say in the cover. She and I and our commissioning publisher hate it with a passion and we are all anxious to change it with the second edition. It’s so awful I can’t bear to put the picture of it here. Good book, if I say so shamelessly, but really, really awful cover – which has made no difference, it seems, to sales as you’ll gather from the reference to second edition.

So let me try to sum up the cover question. I’ve learnt that book covers probably don’t do much other than reinforce the message given by the title and the contents. What matters most is that the cover design allows the title to be read clearly when the image is compressed to the size it appears in catalogues and online. If the design is too busy, or the font is too hard to read, then it won’t compete with those that stand out and say what’s inside, loud and clear. There is also of course the matter of expense in relation to covers, and this goes to the question of anticipated sales – which goes not to the title or cover design, but the actual contents of the book and its anticipated readers. And that’s another post.

So how much does a cover and title and author order matter? What do you think? Do you have other examples to add to mine?

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the Impact of Social Sciences blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

About the author:

Pat Thomson is Professor of Education at the University of Nottingham. Her current research focuses on creativity, the arts and change in schools and communities, and postgraduate writing pedagogies. She is currently devoting more time to exploring, reading and thinking about imaginative and inclusive pedagogies which sit at the heart of change. She blogs about her research at Patter.

I have always given way to publishers on book titles – hence ‘Scottish Politics’ and ‘Understanding Public Policy’ (although I think we managed to get ‘understanding’ removed form the Scottish one). They are a wee bit dull but you know what you are getting.

Great post. I’ve found some reviews here http://www.reviewfinds.com/kindlecover.php in case someone needs it urgently. I’m an author too. I understand that great content itself is not enough. A book is as good as its cover.