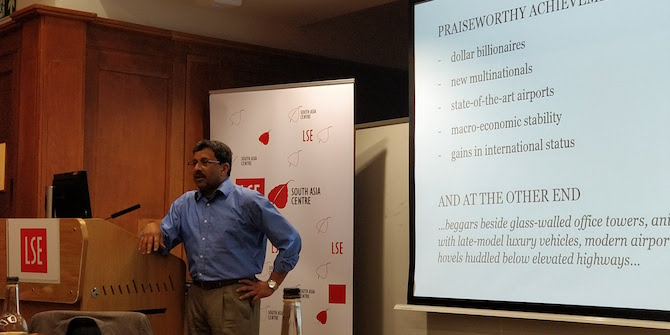

Pankaj Mishra explains how intellectual and political responses by Asian thinkers to western imperialism have shaped Asia as we know it today.

In a new book, “From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia”, Pankaj Mishra redresses the fact that the West has long seen Asia through the “narrow perspective of its own strategic and economic interests”, leaving Asian subjectivities and experiences unexplored. The book recounts the history of the past two centuries from the perspective of Asian intellectuals and activists who had to contend with western domination of their lands and shows how these early attempts to grapple with the West have culminated in present-day Asian organisations and movements ranging from the Chinese Communist Party to Al Qaeda, and Indian nationalism to the global ‘jihad’ of Political Islam. Mishra concludes that the central event of the twentieth century was the intellectual and political awakening of Asia from the ruins of empire, a view that is contrary to western narratives, which tend to focus on the two world wars and the Cold War.

Mishra focuses his narrative on some of the earliest “thinkers and doers” who spurred the remaking of modern Asia. His protagonists include Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (pictured here), a Muslim journalist and political activist who travelled across South Asia and the Middle East in the second half of the nineteenth century seeking to resist European advances in Asia, and Liang Qichao, arguably China’s first modern intellectual. Other individuals who attempted to formulate responses to western incursions – including India’s Rabindranath Tagore, Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and China’s Sun Yatsen – also make an appearance. These individuals initiated the processes whereby resentment against western dominance coalesced into mass nationalist movements and state-building programmes across Asia.

Here, Mishra explains why he chose to focus on specific individuals and considers the legacy of this intellectual engagement with the West in contemporary India.

Q. What made you decide to focus your narrative on al-Afghani and Liang?

A. I chose to write about al-Afghani and Liang because their experiences seemed representative of a certain kind of intellectual journey that many of their contemporaries made: both men belonged to traditional societies, were educated in pre-modern institutions, were exposed to the West at a young age, and then tried to formulate a response to the enormous challenge the West posed to their societies. They, especially al-Afghani, also travelled extensively and came into contact with likeminded people from other parts of Asia. They thus had a wider sense of how other parts of Asia were dealing with the challenge of western imperialism and modernity.

Al-Afghani is also interesting because his thinking encapsulates the many strains of contemporary Political Islam—pan-Islamism, nationalism, Salafism. I was amazed to find that he is not better known, especially since western countries have been grappling with the Islamic response to the modern West, especially since 9/11. In that context, al-Afghani is a crucial figure.

Liang, meanwhile, was the first modern intellectual in China. He launched several magazines, set up schools and trained disciples who went on to become quite powerful. He also had a huge influence on younger readers, including Mao Zedong, who read his works as a young man. Liang’s intellectual journey also dramatised the critique of modernity, which is mirrored by other characters in the book such as Gandhi and Tagore: he started off a Confucian, became a reluctant westerniser, and then returned to Confucianism after realising that western democracy and modernity did not offer all the answers to some profoundly moral questions.

Q. A book like “From the Ruins of Empire” requires an immense amount of research. Did you find the fact-finding challenging?

A. The biggest challenge was not knowing where to stop! I was discovering new things [about the protagonists] all the time. The real challenge was to put together a narrative that could absorb all the information that I came across. Using these characters as a skeletal frame was useful as it allowed me to weave in major historical events around their journeys and amplify other Asian voices in the process.

Q. How do you reconcile the fact that your protagonists and other Asian thinkers who appear in the book simultaneously admire the West, its technologies and organisational prowess, and remain fiercely nationalistic, religious and rooted in tradition?

A. [Asian thinkers at the time] were battling with contradictory ideas. It quickly became clear to them that the West had rapidly and invisibly mustered up an unprecedented power, one that rested on the ability to organise masses of people into active citizens and conscript armies that could deploy better methods to fight wars and develop a grater capacity to kill. Many intellectuals realised that older Asian societies had fallen behind, but none of them were clear on how to catch up. Should they uncritically adopt everything from the West at the expense of their traditions and culture?

Some thinkers identified Christianity as a glue that held the West together, and proposed making Confucianism or Islam a state religion. In fact, there was a hardening of religious identity across Asia in the nineteenth century, whether Hinduism, Islam or Buddhism, as Asian intellectuals tried to transform the solidarity that religion creates into national solidarity. This may seem like a contradictory idea from the western perspective, but it endured as people struggled to understand how to come up with an adequate synthesis to the profound challenge being posed to their deepest values.

Q. Why have these Asian thinkers previously been neglected?

A. They don’t fit very well with the histories of the nation state that we’ve been taught [in Asian countries]. Nationalist histories rely on simplifications, deceptions, if not outright falsehoods—they have very little place for ambiguity in human affairs, which is what these ‘transitional’ men were all about. Meanwhile, the kind of histories manufactured in the West had no place for these thinkers because they focus on the rise of the West. As such, these thinkers can only find a space in the history of cosmopolitanism.

Q. What is the legacy of Tagore’s intellectual journey in contemporary India (Tagore was western-educated and became the first non-European to win a Nobel Prize, but eventually condemned colonial morality)?

A. Tagore is very much a part of the Indian pantheon, particularly having authored the Indian national anthem. But he is the most unlikely author of any national anthem (Tagore also wrote Bangladesh’s national anthem). He was a consistent, almost bitter critic of nationalism, especially the sort propagandised by nation states, and repeatedly warned his compatriots against it. Tagore would probably be appalled by the way the Indian state has behaved with its religious and ethnic minorities.

Modern-day India has abandoned a lot of the founding ideals of people like Tagore and Gandhi—this phenomenon of turning your back on the first generation of thinkers is not confined to Indiaand can be witnessed in Chinaas well. Many things that Tagore explicitly warned against, especially nationalism, have become a very significant part of India’s political life. You can speak of this as a terrible betrayal of Tagore’s ideas.

Q. According to western narratives, the economic growth of India and China is a result of the countries adopting western practices. Conversely, in the book, you argue that the rise of India and China is a culmination of a long struggle against western imperialism. How do you reconcile these viewpoints?

A. There’s a straightforward imperialist narrative, according to which the West made the modern world and set the global standard with innovations such as the railways and democracy. This long-standing tradition has been renovated in recent writing about India and China, which argues that these countries are now converging on the great example set by western powers by mimicking the West and adopting free market capitalism and unleashing entrepreneurial energies. This ideological perspective borrows a great deal from the older narrative, which says that there’s only one history, that of the West, and everyone just has to catch up.

But the reality is that most Asian states grew out of political movements that were spurred by imaginations and subjectivities seeking to counter European imperialist dominance. They had to become nation states, and then become extremely strong in an international context, by whatever means necessary, so that they would not have to endure the suffering they endured under the Europeans. So China, for example, adopted Communism, and when that didn’t work, they liberalised their economy. It would be a mistake to discount the Chinese nationalism that has driven developments in China over the last few decades, and it’s a ludicrous fantasy to think that China will be built in the mirror image of the West. The history of Asia shows that there is more than one history of modernity.

Q. Your book describes how early anti-imperial sentiments have transformed into radical Islamist movements in Muslim countries today. What is the legacy of anti-West thought in present-day India?

A. The Indian version of anti-westernism, especially the Hindu nationalism articulated by the RSS and BJP, can be extremely xenophobic. At the same time, it aspires for a partnership with the modern West, which is a unique feature—you don’t see this in the anti-West movements in Muslim and other countries. This occurs partly because Hindu nationalism is a middle-class, upper-caste and conservative phenomenon rather than a mass revolutionary movement; it’s the defensive ideology of social and economic elites entering the modern world, and wanting to preserve and expand their privileges often through the help of the West (not surprisingly, the main funding for the BJP comes from non-resident Indians and that India has snuggled closer to the United States and Israel in recent years). For Hindu nationalists, the dignity and equality that so many Asians struggled for can be attained through a process of appeasement of and collaboration with the West.

Q. What should a western reader take away from this book?

A. Narcissistic western histories have created such an intellectual desolation as far as Asia is concerned that a general reader of these histories is unlikely to even know the names of the leading writers and intellectuals of Asian countries. The least this book can do is to impart a sense of how some of Asia’s most educated people responded to western encroachment on their lands, how intelligent and sophisticated their response was to that encroachment, and how that response has shaped the world we live in today for better and for worse. In short, the history of the West is not the history of the world.

Click here for a podcast of Pankaj Mishra’s public lecture on these themes at LSE.

Pankaj Mishra is the author of “Temptations of the West”, “An End to Suffering”, “The Romantics” and “Butter Chicken in Ludhiana”. He writes regularly for The Guardian, New York Times, New York Review of Books and New Statesman.