A new project by the Open Society Foundations maps changes affecting the democratic service delivery of news on political, economic, and social affairs. LSE alumna Hemal Shah reviews their study on India, and interviews the lead author on his perspectives on media digitisation in India.

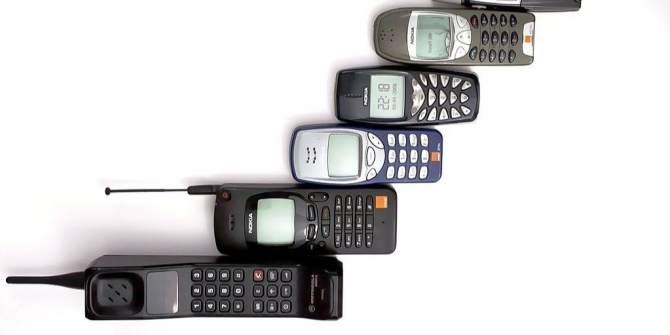

It was often unclear what the transition to digital media – the switchover from analogue to digital broadcasting, growth of new media platforms, and convergence of traditional broadcasting with telecommunications – would mean for less developed societies. More democracy and openness, or the opposite? New media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have been credited with empowering citizens, even inspiring democratic revolutions like the Arab Spring; or, in India’s case, mobilising mass movements against corruption. Despite such events, discussions about digitisation in the developing world continue to focus on the fallout of the ‘digital divide’ (economic disparities leading to unequal access to digital technologies).

In light of these debates, the Open Society Foundations (OSF) has launched Mapping Digital Media, a project which assesses the risks and opportunities of digitatisation in 60 countries. Their new study on India under this project highlights how fears of the digital divide may not be as worrisome as they are made out to be: as many as 800 million Indians have mobile phone connections; about 60 per cent of households have cable and satellite television access; 92 per cent of the total population of 1.2 billion-plus can access the public news channel Door Darshan. As a result many of the 300 million Indians who live below the poverty line participate in the digital world.

A more relevant concern in the Indian context is protecting public interest in an era of digitisation—especially in areas such as maintaining standards of professional journalism, impact on business, transparency in licensing, and accountability and autonomy of the state broadcaster. Vibodh Parthasarathi, lead author of this study and professor at Jamia Millia Islamia, explains that the “gradual unfolding of convergence prompted such an inter-sectoral, policy-oriented report to map the complexity of the news media ecology, as opposed to the conventional sector-wise (telecom, internet, broadcasting, press) or thematically compartmentalised (news, content filtering, FDI caps, technology standards) commentaries on the media.”

This study finds that news channels are primarily financed by private advertisers as a result of which viewership numbers matter more than journalism. Superficially, this model has increased choice. But as the report points out, the increase in news diversity remains uncertain as research shows that content aired across mushrooming news channels is very similar. On the other hand, expanding literacy has also meant an increase in print readers, in contrast to declining print readership in other countries. “Proprietors seek to burrow deeper into untapped sub-regional and local advertising markets, which explains the numerous editions of non-English dailies like Dainik Jagran,” explains Parthasarathi.

The growth of the media market has also undermined the quality of journalism. Some journalists have played the role of “crusaders”, making issues they raise very popular. And while some reporters are able to do more and better quality investigative reporting, the majority of journalists are succumbing to the pressure to be “first” in the face of innumerable new platforms; consequently, ethics and the quality of news offerings are compromised. The report also argues that easier access to information has made journalists “lazy”and disinclined to pursue serious, long-term investigations. Also, unlike before, pressures from “powerful interest groups” to stop pursuing a story on television or online are heightened as content can instantly be withdrawn.

That said, media digitisation has empowered minority groups whose issues were otherwise underreported by the national media. An “absolute increase” in the number of linguistic and regional news outlets has boosted local-level reportage of marginalised concerns, which are then picked up by the national media. It is also surprising to note that across the top 10 language dailies, readership of Times of India (English) has fallen compared to most of its peers like Dainik Jagran (Hindi), Dinakaran (Tamil), Ananda Bazar Patrika (Bangla), or Eenadu (Telugu). Independent websites of various factions in Kashmir, Dalit advocacy groups, and sexual minorities have also gained ground. In fact, independent mobile and online initiatives have expanded the media’s watchdog function with regards to the government, corporations and the mainstream media. This growing media space, however, is not properly regulated despite the fact that SMS news alerts and news sites are the most frequently accessed types of content via mobile phones. The lack of dedicated regulation has often led to sudden impositions to minimise the risk of defamation. In August 2012, for example, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) limited the number of SMS/MMS sent by pre-paid mobile users to 20 per day for 15 days to control hate speech targeting the Assamese around the country when violence broke out in the state of Assam.

Digitisation also has the potential to reduce costs for businesses by expanding niche channels, portals and websites on one hand, and offering shared costs and bundled opportunities to advertisers on the other. Bennett, Coleman and Company Ltd is a fine example with its diversified portfolio comprising The Times of India, Economic Times, Times Now news channel and indiatimes.com. However, many other renowned businesses like the Network 18 Group, including the likes of CNN-IBN, have failed to harness dividends from convergence opportunities. In addition, the fragmented process of policymaking has resulted in uneven growth and protocols across the media. The report suggests that a combination of these issues may have led some businesses to resort to “unorthodox” practices of resource mobilisation, including private treaties and paid news. The study rightly notes: “Such an institutional milieu…creates a fertile ground for politicisation and favouritism in decisions on resource allocation, licensing criteria, and ownership protocols.”

The impact of digitisation on broadcast ownership is yet to unravel itself; the absence of an overarching regulatory framework leaves many legal loopholes on cross-ownership and concentration. Parthasarathi explains that “most last-mile cable relays are owned by small, localised entrepreneurs who are unable, or unwilling, to afford expensive equipment requisite for the digital switchover. So by compulsion or by choice, they prefer to sell off to large cable operators, inviting a spate of consolidations by such national or regional operators, as initial trends in Delhi reflected.”

This OSF study defines the strengths and weaknesses of a digital switchover in the Indian context, and reveals policy gaps which need to be addressed immediately. Currently, debates on policy options remain confined only to two issues—maximising government rents rather than public interest and nurturing private enterprise often at public cost. The authors highlight the urgent need for more independent, evidence-based decision-making to expand the scope of policy options and debate. And what is the fundamental impact that Parthasarathi and his colleagues hope for? “We want people to ponder these issues in an integrated and nuanced manner, rethinking the typical canvas of the numerous ‘sectoral’ reports brought out by government, trade bodies and consulting companies.”

Hemal Shah is a policy researcher at the Legatum Institute, a London-based think tank. She completed her Masters in Development Studies from LSE in 2010. Follow her on Twitter @hemalshah_7

Is it possible for a local cable operator with a subscriber base around 1000 get a licence for digitalisation of his network?