Using the example of the 2005-2015 Bangalore Master Plan, Jayaraj Sundaresan challenges the reliance on international expert knowledge when it comes to planning Indian cities.

What do they know about Bangalore? I mean the urban planning experts from Paris who were contracted to make the 2005-2015 Master Plan of Bangalore. I wonder how anyone could assume that a master plan produced through effectively deploying their GIS machines, population projections, ideologies of good city form and so-called, state-of-the-art knowledge could put to order an unruly city of 8.5 million. Comprising of Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme (APUR), the City Government of Paris, Institute d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme de la Région d’Ile-de-France (IAURIF), Université de Sorbonne, and Group Huit, an eight-member team of urban development consultants working through the office of Group SCE India Private Limited in Bangalore, the consortium sounded entirely out of place. However, this was one of the most ambitious technical exercises that had been carried out in the 60-year planning history of Bangalore.

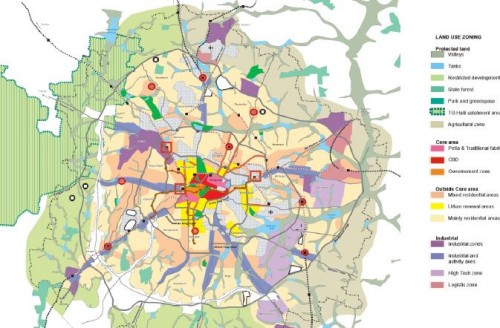

Source: Bangalore Development Authority

Source: Bangalore Development Authority

In an article to a GIS portal, one of the technical heads of the team argues that the master planning process brought together 110 experts, “consisting of town planners, architects, economists, demographers, sociologists, GIS & IT specialists, geographers, cartographers, infrastructure and transport specialists” to create the Metropolitan Spatial Data Infrastructure (MSDI) that provided the information base for the Master Plan. This final MSDI layer consisted of about 80 information layers generated by the data collected from over 30 administrative organisations in Bangalore as well as surveys from many ground control points.

The process produced an updated and sophisticated data infrastructure, a vision document for a globalising metropolis and a land use plan to enable that ambition, all within two years of the consulting period. The Master Plan vision document argues: “The planning methodology attempts to ensure that neighbourhoods, the city and the region accommodate growth in ways that are economically sound, environmentally responsible and socially supportive of community liveability, now and in the future”. To this end, “it identifies development patterns, infrastructure gaps and deficiencies, project and reform priorities and an implementation schedule that would be both fiscally realistic and innovative.”

This is an all too familiar discourse abundant in the many versions of normative planning theory circulating in western countries about sustainable growth, compact cities, new urbanism, transport-oriented development, good governance and so on.

The contract cost 24 crore rupees. But it was French money organised through an Indo-French protocol and it provided a number of jobs for French experts some of whom were already engaged in documenting infrastructure for potential privatisation of Bangalore’s water supply. Furthermore, it satisfied the city’s ‘glocal’ elites who were upset at the lack of accountability, capacity and transparency of Bangalore’s own planning system. On the basis of this experience, the consultants have since procured new contracts for master planning other large Indian cities.

Unlike many master plans that haven’t been updated for decades, the Bangalore Master Plan was prepared in 18 months—submitted in 2005 and adopted in 2007. So shouldn’t everyone be happy? Isn’t this a success from a number of angles? After all, didn’t the consultants deliver a free Master Plan for Bangalore?

Moreover, isn’t this business as usual when it comes to high-profile urban planning in India? High flying international planning experts who know little about urban life or urban politics in India make plans that the city’s residents are expected to live by. Notably, these consultants, like the French in Bangalore, are often invited by local elites who believe in the power of state-of-the-art planning knowledge and practices from abroad. Thanks to World Bank norms for shortlisting consultants – used by the government agencies – such consultants often become default finalists due to their international experience and economic capacity to prepare a technical and financial proposal for free.

From the time of the Ford Foundation-led Master Plan for Delhi in 1962 and Calcutta in 1966 to the master planning of T-Nagar in Chennai in 2010, expert global knowledge has been relied on to order the urban transformations in India (Banerjee, 2005). But why should this bother us? Cities in India are anyway an assembly of many forms of creative and destructive violations. Not many people actually live the plan. How can they, when large areas of the city – for instance, the so-called informal settlements – are demarcated as an unclassified (therefore invisible) category in the Plan? About half of the population in large Indian cities lives in informal settlements or slums. The land use plan of the 2005-2015 Bangalore Master Plan classifies the informal settlements as unclassified as opposed to formal settlements, where categories such as residential, commercial, industrial and so on are used.

The plan and planning process are the most contested but seldom recognised aspects of urban conflicts in everyday life. Knowledge about urban conflicts is dominated by examinations of claims over space and time or conflicts between social groups—for example, claims over public land or security of tenure, squatting and evictions, history and heritage, ethnic or communal conflicts. However, conflicts over the knowledge, paradigms and assumptions that define, regulate and normalise everyday urban living are seldom examined by scholars in urban theory and planning studies on India. The trajectory of the 2005-2015 Bangalore Master Plan is a useful case in point to understand how ‘expert knowledge’ of international planning and its institutionalisation has been challenged at every stage by the ‘lay knowledge’ and practices of everyday politics that constitute urban life. This is discussed in the next post under this headline.

In Part Two of this post, Sundaresan describes how local political networks, neighbourhood groups and the state legislature challenged the authoritative expert knowledge that informed the 2005-2015 Bangalore Master Plan.

About the Author

Dr Jayaraj Sundaresan completed his PhD in Regional and Urban Planning Studies from LSE’s Department of Geography and Environment in 2014. His PhD dissertation is titled “Urban Planning in Vernacular Governance: Land use planning and violations in Bangalore”.

References

Tridib Banerjee, Understanding Planning Cultures: The Kolkata Paradox; in Sanyal (ed), Comparative Planning Cultures, Routledge, 2005.