As the annual UN talks take place in Lima, Lexi Aisbitt assesses what can be deduced with respect to India’s broad strategy on climate change. She stresses the need to act decisively, as parts of the South Asian subcontinent are already feeling the effects of the global ecological imbalance.

As the annual UN talks take place in Lima, Lexi Aisbitt assesses what can be deduced with respect to India’s broad strategy on climate change. She stresses the need to act decisively, as parts of the South Asian subcontinent are already feeling the effects of the global ecological imbalance.

The past two weeks have seen thousands of global delegates in Lima to attend the annual UN climate change talks. Understood as an essential exercise in the groundwork required for a successful deal at the subsequent conference in Paris next December, the negotiations bring to an end a year in which climate change has latterly appeared firmly back on the agenda.

Publication in September of Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything (reviewed on LSE Review of Books), raised in a succinct way the necessity to combat the seemingly inevitable destruction of climate change by reimagining our relationship with capitalism, development and economic prosperity. In October, an EU-wide pact to cut emissions across the European Union by 40% of 1990 levels by 2030 was announced. This set the stage for the subsequent revelation in November of a historic US-China pact in which the world’s two largest emitters of harmful greenhouse gases agreed ambitious reduction targets. Although the outcome of the Lima talks is currently unknown, for many there looms a large unanswered question: what about India?

It could be argued that India possesses unique significance in any successful global strategy to combat climate change. Ranking third in the world for both the size of its economy and its levels of harmful gas emissions, India is likely to top both of these lists as it continues to experience dramatic growth in the coming decades. Simultaneously, it remains the home of the highest percentage of the world’s extreme poor (according to the World Bank). It is also undoubtedly one of the areas most at risk, with a UN report published ahead of Lima claiming India was in the top 20 regions on earth where the disastrous affects of climate change would be acutely felt in fifty years time.

With feet in seemingly opposing camps, the case of India neatly encapsulates the central challenge underlying the negotiations taking place in Lima. The purported aim of all involved is to balance the urgent need to reduce emissions across the board whilst simultaneously avoiding harmful impacts on the development prospects of poorer nations. Tensions rise sharply when the richest nations demanding universal commitment to reductions are pitted against developing countries who have contributed very little to emission levels thus far, require significant funds to develop greener technology whilst maintaining growth, and will also be most severely hit by the environmental changes predicted if they continue to rise.

So what can be deduced from the UN talks with respect to India’s broad strategy on climate change?

The strapline item garnering the most attention is the country’s pledge regarding solar energy. Having built the world’s largest solar plant in his home state of Gujarat, Narendra Modi has set out plans to create a 50,000 person ‘solar army’ dedicated to increasing India’s solar capabilities five fold by 2017. The attractiveness of turning to this renewable power source is underscored when air pollution levels are considered, with Delhi topping WHO rankings for the world’s worst city in terms of air pollution. Though India’s representatives in Lima remain coy about the exact extent of their emission reductions, the announcement at the conference of the Climate Change Performance Index, in which India is ranked as moderate, gives cause for optimism.

Nonetheless, India’s continued commitment to the use of coal represents a serious cause for concern. The country’s Power Minister has promised to double the country’s domestic consumption of coal to in excess of a billion tons by 2019. This would have a huge impact on global emission levels whilst also destroying vast tracts of the environment where the mines are located. Then there is the devastating human cost, of the barbaric and exploitative working conditions of the mines themselves, the livelihoods destroyed as civilians are shifted from their homes to accommodate aggressive and expansive mining projects, the towns and cities rendered unliveable due to extreme levels of pollution, as well as the longer-term threat to India’s people.

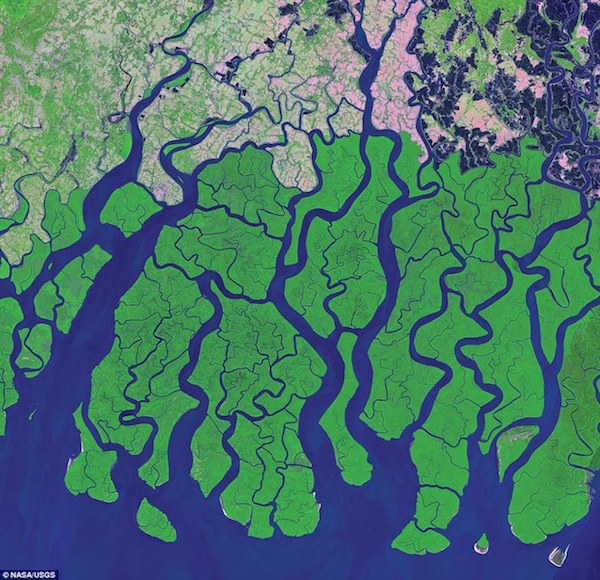

On the fringes of India in the Eastern state of West Bengal, the effects of climate change are already visible. The Sundarbans (literally meaning beautiful forest in Bengali) is a UNESCO world heritage site straddling the India-Bangladesh border. Spanning approximately 10,000 square kilometres, it is the largest contiguous mangrove forest in the world, home to hundreds of unique and endangered species, including the Bengal tiger.

Yet this vast region is gradually disappearing. Rising sea levels, ecological degradation and unpredictable and increasingly violent storm surges are decimating this natural barrier to tides and flooding along the India-Bangladeshi coastline. A report published by the Zoological Society of London almost two years ago showed that in 71% of the Sundarbans area the coast was retreating at a rate of 200 metres a year. If this rate were sustained, the report suggests, this same percentage of the region would have disappeared within 50 years.

Though there are calls to preserve this endangered environment, and particularly perhaps India’s most symbolic of species, often overlooked remain the millions of people who inhabit these islands. The population of the Indian side of the Sundarbans is 4.2million (Indian Census 2011), the majority of whom rely on what may be an increasingly hostile environment to provide their livelihoods. Fishing, prawn seed trawling, wood cutting, small scale farming and honey collecting are the predominant occupations detailed in Annu Jalais’ rich ethnography of the region in which she explores the challenges of conservation and climate change from a lived, bottom up perspective. In doing so, she grants an insight into the daily struggle of those hemmed in by rapidly changing ecological circumstances and well-intended conservationist principles that seek to limit their ability to depend on and interact with their environment.

In places across India where ideas of nature are intrinsically intertwined with those of self, livelihood and society, one is left with a sense that for millions of people the relationship with their surroundings may already be critically compromised by both economic, developmental changes and the effects of global ecological imbalance. As the talks in Lima draw to a close, this may be a stark reminder that though the ‘threat’ of climate change is something worth fighting against, many of the changes have already begun.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting

About the Author

Lexi Aisbitt is a doctoral candidate in LSE’s Department of Anthropology. Previous posts by Lexi can be viewed here.

Lexi Aisbitt is a doctoral candidate in LSE’s Department of Anthropology. Previous posts by Lexi can be viewed here.

.