Guest blogger, Dr Chrissie Gale, international lead for CELCIS (the Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland), tells us about her latest work which has the potential to shape the drive for better alternative care for children in countries around the world.

Caring for children who haven’t had the best start in life is something we all want to get right. Here in Scotland, this is something we take seriously. It’s reflected in Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC), our national approach to improving outcomes for children.

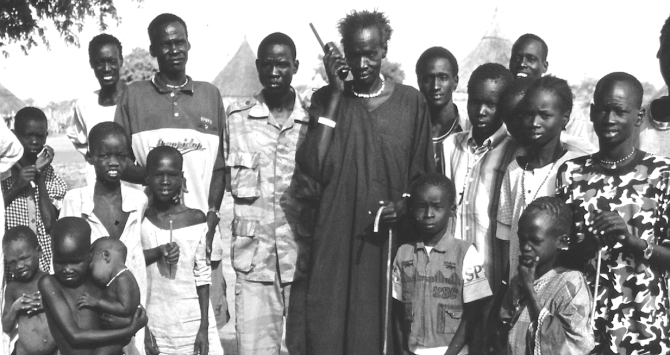

But we are not alone in our ambitions to improve the life chances of our children. Across the globe, for many different reasons, hundreds of thousands of children cannot live with their parents. ‘Alternative care’ is the provision of a safe and caring setting for children to live in whilst they are unable to stay with their families – adoption being an example of this. There are many instances of governments and communities rising to the challenge of providing better alternative care for children.

How does the care system work globally and how can we improve it?

This is the exact question I, alongside colleagues at SOS Children’s Villages International, set out to answer in our recent report as the result of a European Commission project. We looked at three different continents – Asia, Africa and Latin America – and assessed what their alternative care systems look like.

We discovered that the popular assumption that national laws, standards and policies are the blockers of providing improved alternative care for children wasn’t necessarily true. Instead, lack of political will to implement regulations and put resources in place to develop a skilled workforce is the bigger mountain to climb.

In many countries policies imported from developed countries are not culturally or contextually appropriate. Countries need to develop practices that are right for them. Around the world, most children out of parental care are in extended family or kinship care. Great care is needed not to impose ideas such as foster care with strangers where that might break down what already exists.

Governments should obviously concentrate on preventing family separation, but also provide the most suitable alternative care for children where separation is absolutely necessary.

Fostering dogs

Throughout the research process I went to Chile, Ecuador and Nepal and found some amazing positives. For instance, I visited an SOS Children’s Village where the woman in charge had a problem of children bringing stray dogs home. She put the dogs back on the street but they always came back. Thinking outside the box, she got the children to foster the dogs. It helped them see what it’s like to take someone vulnerable and care for them, with the idea of getting them back into the community, to a family. It also tackled the dog problem.

Residential facilities as private businesses

On the negative side we saw residential facilities set up as private businesses. Owners encourage families to bring children in promising, for instance, better education so they could make money from donors.

Some donors are individuals: in Nepal, trekkers visit a so-called orphanage, become friends of the ‘orphanage’ and go back to Europe or North America to raise money for it, sometimes through a small firm or church. But over 95% of the children have families, and if families were supported with this money they wouldn’t give up children in the first place.

To me, this was the most worrying finding. The lack of knowledge that donors have in the western world of where their money is actually going to needs to be addressed, and promptly.

Voices of children

What was absolutely crucial as part of the research process, was listening to and understanding the voices of the young people themselves. We heard from more than 170 children and young people. The priority for all was family, even for those from very poor families or at risk of harm. They wanted their families supported so they could go back after a period of being in care. They usually stay in the care system until they are 16 at least. Once they leave care, they are homeless, with no network or social skills, and their families don’t know them. This is hugely challenging and is a vicious circle that needs broken.

Towards a better future

The European Union has worked tirelessly for years in central and Eastern Europe and former Soviet Union countries to eliminate large residential institutions for children. They now wants to take the lessons learned to other places, hence why we embarked on this project.

In the past 10 to 15 years many countries have developed a legal and policy framework around looked-after children but, as explored above, we found the real challenge is implementing those rules.

We have gained real insight into how to improve things, which has led to recommendations we hope make a positive and lasting difference to children all over the world. One of the most crucial of these being that the European Commission should educate donors to stop the flow of money from developed countries to harmful institutions.

It’s about gatekeeping: services should prevent the gate opening unnecessarily for children to go into alternative care, and open it for children to come out. The EU is committed to making positive changes for children at risk of separation from their families or already in alternative care: this research is a first step to informing future policy and galvanising resources to make those changes.

Dr Chrissie Gale is international lead at CELCIS (the Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland), part of the University of Strathclyde.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.