Quantitative analysis of historical ‘big data’ can help to explain how record-making practices around death facilitated policies of repression and control, writes Tamy Guberek (University of Michigan).

• Disponible también en español

“Prefiero guardar silencio” – I prefer to remain silent – were the only words uttered by former Guatemalan president José Efrain Ríos Montt to the victims of military massacres under his rule when he finally stood trial for genocide and crimes against humanity in 2012.

In Guatemala, the state institutions that used extreme violence to silence opponents throughout the 20th century also obfuscated their records. The unacknowledged silences in these records are powerful, reinforcing the impunity enjoyed by their creators.

The National Police and death in Guatemala

By studying and detecting deep silences in the surviving records of Guatemala’s defunct National Police (PN), archivists at the Historic Archive of the National Police (AHPN) have been able to establish the criminal responsibility of former police leaders and officers for their human rights violations, including the forced disappearance of Edgar Fernando García, Édgar Enrique Sáenz Calito, and several others missing since the 1980s.

Working together with them, I have discovered that not only did politicians and bureaucrats censor information and destroy records, they also created silences via misleading terminology and classification in records of everyday events.

At the height of state violence in the 1970s and 1980s, the PN was one of the main forces of repression in Guatemala’s urban centres, including via death squads formed with the military and intelligence agencies The PN also played a central role in surveillance over the city centres, tasked with monitoring the population and recording the movements of those perceived as a threat to the military regime.

The PN’s relationship with death was an intimate one. As police officers, they oversaw and documented the removal of dead bodies. As perpetrators of human rights violations, they committed, aided, and abetted state-sponsored killings and disappearances.

More than twenty years into the search for truth and justice, knowledge about state-sponsored death continues to be elusive. But what do the PN’s records hold – and hide – about these deaths?

Analysing the Historic Archive of the National Police

The AHPN is historic big data. Its 80 million documents contain an overwhelming amount of evidence from over a century’s worth of official police records.

Determined not to let this sheer magnitude guard the secrets held within it, the AHPN and the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG) collected a random, statistical sample of the archive documents in order to code information about document creation and acts of interest, such as crime, violence, and human rights violations.

The sample included every type of document created in the normal course of business, whether mundane or confidential, from the pen of the lowest PN agent or the typewriter of the Director General. With this dataset I could tease out patterns in their written words.

More specifically, I analysed the literal nomenclature employed in recording deaths from 1978 to 1986. This was a crucial period that covered the peak of the military’s counterinsurgency campaign and the country’s transition from over thirty years of military dictatorships to civilian rule.

To understand the meaning conveyed by each death term, I manually scrutinised hundreds of records, uncovering observable and regular differences:

- “Homicidio” (homicide), an explicitly legal term, was often accompanied by rich disclosure of information about the context, weapons, and alleged perpetrators surrounding the death, but little information about the victim.

- “Asesinato” (assassination) denoted intentional killings, sometimes including the identity of the arrested or alleged perpetrator.

- “Cadáver” (cadaver) indicated a lifeless body and often came accompanied with a description of the cause of death, the place where the body was found, and whether or not the body was identified – overwhelmingly, they were not.

- Finally, descriptions of other generic “muertes” (including “muerto,” “fallecido,” “perecido”) contained little information about the circumstances surrounding the death.

Terms were used consistently, and each conveyed a different degree of visibility and invisibility about the death it described.

Calling death by its name: differences across military regimes

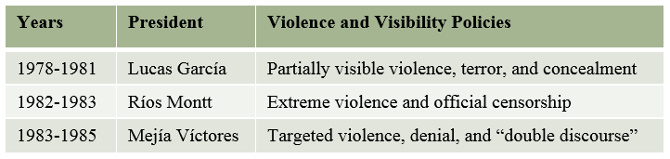

During this dramatic period, the three military regimes that held power during this time were extraordinarily repressive and violent, yet each was distinct in its modus operandi and its means of controlling and censoring information about violence:

How are these differences in policies and practices of violence and visibility reflected in the documents of a large, bureaucratic, state security institution?

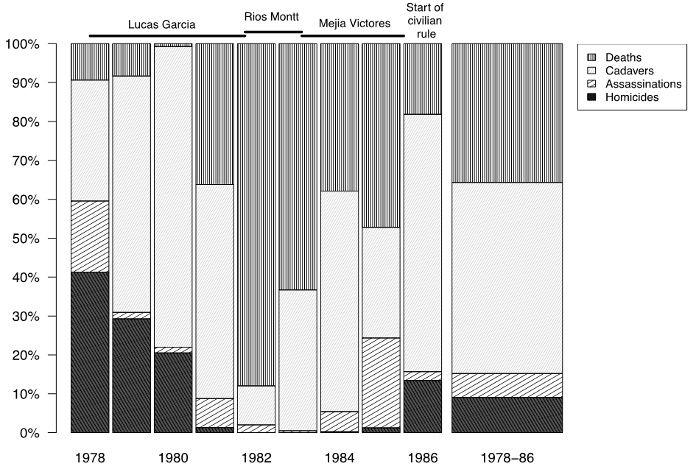

The graph above presents estimated proportions of police usage of each death term by year. It reveals striking changes in the ways that death was recorded during this volatile period. Most notably, the use of ‘‘homicide’’ – the legal term often accompanied with greater disclosure about perpetrators and context – decreased considerably in 1981, appeared very rarely from 1981 to 1985, and was not used at all in 1982 or 1983. These patterns align roughly with the information policies of each of the three regimes.

Between 1978 and early 1982, the Lucas García regime used the spectre and visibility of violent death – epitomised by daily news about cadavers on public roads – as a terror tactic to deter opposition and popular mobilisation. Accordingly, documents from those years contain more varied information types of death and perpetrators than the documents from the two subsequent regimes.

Ríos Montt used the rhetoric of ‘‘cleaning up’’ crime and chaos to justify his coup, his extreme violence, and official censorship. In the PN records from 1982, a clear majority of deaths were recorded using generic ‘‘death’’ terminology, providing the the least amount of information about the nature, cause, or circumstances of the death. That same year, use of the term ‘‘cadaver’’ also fell to a surprising low.

In mid-1983, when General Mejía Víctores ousted Ríos Montt in another coup, the PN’s record-making practices shifted again. The new PN director, Hector Bol de la Cruz, authored numerous extended memos detailing his vision of current events, policing policies, practices of violence concealment, and the obfuscatory manipulation of language. This period saw the highest rate of enforced disappearances during the military dictatorships. Terminology is more varied during this period, with evidence of orders to modify descriptions of death in the official records.

What’s in a name? Terminology, truth, and justice

Death was a painful and all too present reality for individuals, families, and society at large during these violent years. But even today, the ongoing search for truth and justice is hampered by the distorted data produced by record-making practices of that era.

Terminology in records and archives can systematically render phenomena more or less visible. And contrary to ideas of inertia in such huge bureaucracies, what was included in the official records, how they were written, and how those records were read underwent stark shifts as political and institutional environments changed. Given the PN’s central role in providing information to the judiciary and the press during this period, other sources are also highly likely to have been affected by the PN’s internal recording practices.

The quantitative probe of silences presented here, coupled with archival and historical research, can help to peel back one explanatory layer of how even basic and routine documents about death enabled regimes to implement policies of repression and control.

As courageous activists in Latin American societies – not only Guatemala, but also Colombia, Mexico, El Salvador and beyond – use state archives to fight for truth and justice, they inevitably inherit legacies of silence that can continue to wield power over the present and future if left unidentified and uninterrogated.

The lesson we must learn from the admirable work of Guatemala’s AHPN archivists is clear: to break the power of these silences, records cannot simply be read at face value.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This post draws on the co-authored article “On or off the record? Detecting patterns of silence about death in Guatemala’s National Police Archive” (Archival Science, 2017)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting