Pope Francis’ attempts to move the Catholic Church beyond the conservative sexual agenda of his predecessors have been undermined by abusive sexual practices within the Church itself, writes José Manuel Morán (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, CONICET).

Pope Francis’ attempts to move the Catholic Church beyond the conservative sexual agenda of his predecessors have been undermined by abusive sexual practices within the Church itself, writes José Manuel Morán (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, CONICET).

• n.b. republished courtesy of Sexual Policy Watch; Creative Commons licence does not apply

Things did not turn out as expected in Chile.

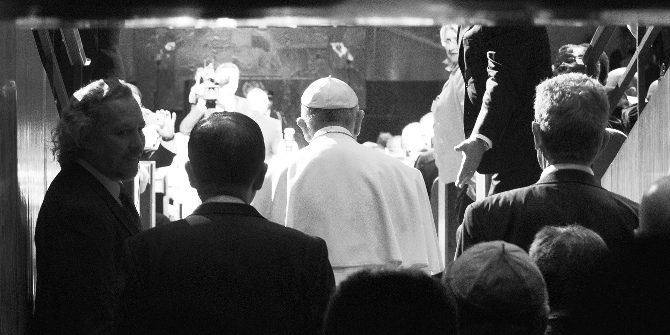

Pope Francis, whose image as a charismatic leader sharply contrasts with that of his predecessor Benedict XVI and who often deploys discourses that distance themselves from those promoted by John Paul II in his obsession with sexuality, was not as successful in connecting with Chilean people as on previous visits to Latin America.

The Pope was harshly criticised, even by local Catholic communities, in particular due to his lack of empathy towards victims of sexual abuse committed by Chilean priests. To many observers, the Pope’s visit to the country was the worst Francis has undertaken since he took office.

The Chilean context

What happened in Chile? Why didn’t the Pope attract religious people in the same way as in other Latin American countries?

Chile, while sharing a common history with the rest of the region, has certain peculiarities that differ from other regional contexts, which may underpin the failure of the papal visit in January, 2018.

At least two factors can be mentioned:

- The impact that the clergy’s sex-abuse scandals had on people’s religious identification with the Church seems to be different from the rest of Latin America.

- Francis’ marked disconnection with the “popular world” and Chilean social movements seems to be unprecedented in the region.

Sexual abuse, distrust, and religious disaffiliation

When Francis landed in Santiago on 15 January 2018, he arrived in a very different country from the one visited by John Paul II in 1987.

The current democratic context contrasts sharply with the dictatorship that ruled the country at that time. Chile’s strong Catholic identity during the 1980s differs from a scenario of disenchantment with religion that has become increasingly evident in the last few years. In fact, Chile features amongst the very small group of Latin American countries that has seen the number of Catholics decline, not due to the rise of evangelism but rather because of a growth in the percentage of people identifying as non-believers.

Between 1995 and 2017, the percentage of Chileans who recognised themselves as Catholics fell dramatically from 74 to 45 percent, while those not belonging to any religion increased from 7 to 35 per cent in the same period. This marks an important difference with most of the countries in the region, where Christianity – whether in its Catholic or Evangelical versions – remains prevalent.

Although the phenomenon of religious disaffiliation has multiple causes, the most important seems to be the growing critique of the Catholic Church by Chilean society with regards recent cases of clerical sex abuse.

A key turning point in this respect came in 2010 with allegations of repeated abuses against minors by the priest Fernando Karadima in Santiago’s “El Bosque” parish, which was widely covered by the media.

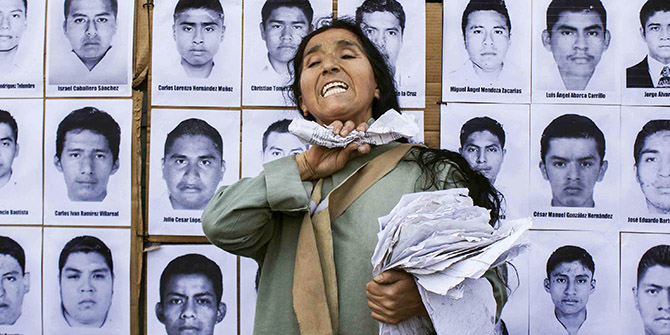

This sparked discovery of other serial cases of sexual abuse performed by the ecclesiastical hierarchy throughout the country, which then made public 78 complaints against priests. The Chilean Catholic Church’s image could not survive intact after this wave of allegations.

Recent studies show a marked decrease in citizens’ confidence in the institution in recent years, with a dramatic decline between 2010 (the Karadima case) and 2011. In just one year, public trust in the Church fell from 61% to barely 38%, making Chile the society with the least trust in the Catholic Church in all of Latin America. Between 2010 and 2017, the percentage of people identifying with no religion also increased from 18% to 35%.

Francis was aware of the sex-abuse scandals upon arrival in Chile. In a speech delivered from La Moneda presidential palace alongside President Bachelet, he did not hesitate to beg forgiveness for these episodes.

For many people, however, his words were undermined by his concrete actions, as he not only refused to meet personally with victims, but was also accompanied by Juan Barros, the Bishop of Osorno, at all of his public events. The same victims who denounced Karadima had also accused Barros of witnessing and covering up the abuse.

Minutes before the Pope boarded a plane to Peru, a group of journalists asked him about Barros’ presence during all of the religious acts. His response was:

When they bring me a proof against Bishop Barros, I’ll talk. I have not seen a single piece of proof against him. All this is a slander. Is that clear?

In a context marked by increasing levels of religious disenchantment, the Pope’s words were harshly received by Chilean society. Unlike elsewhere in the region, the Chilean sex-abuse scandals have clearly been leading Catholics to massively desert the institution, breaking their ties with the Church and developing more critical attitudes towards it.

The hierarchy of the Chilean Church expected that the highest leader of the Vatican would firmly condemn the abuses and listen to the victims in an attempt to contain the wave of disaffiliation. But, on the contrary, his parting words appear only to have deepened disenchantment with Catholicism.

Francis and the “popular world”

While the sexual abuse issue was the main focus of attention during Francis’ visit, there is a second factor that may explain why the Pope did not generate the same enthusiasm registered in his previous visits to the region: his lack of connection with the mobilised “popular world”.

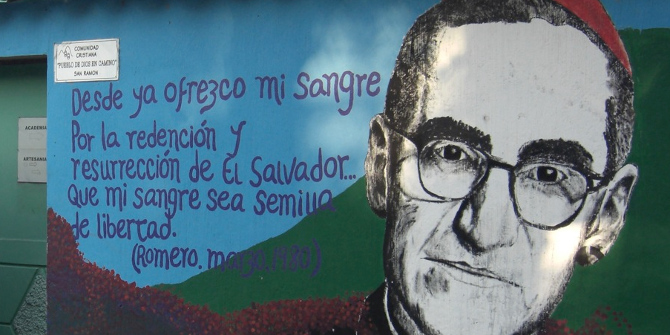

Francis has achieved greater proximity with Latin American social movements thanks to the discursive turn he made with respect to – and in opposition to – his predecessors, which has captivated many citizens. John Paul II and Benedict XVI invested their energies in strengthening a conservative sexual agenda and fighting against progressive interpretations of biblical texts, especially those deployed by liberation theology and often inspired by Marxist views.

Without necessarily modifying the conservative content of Church doctrine, Francis is instead playing an ambivalent game in which he allows himself to strategically shift the conservative sexual agenda into the background, either by providing more nuanced versions of it or by prioritising a renewed critique of capitalism (as a “throwaway culture”) and a focus on poverty.

Leaving aside discussions on whether Francis’ politics represent a structural change for the Catholic Church or just a discursive turn seeking to co-opt new allies without modifying conservative Vatican politics, it is undeniable that these renewed papal speeches have attracted the attention of mobilised popular sectors.

For example, some key Latin American organisations participated in the “World Meeting of Popular Movements” held in Rome in 2014, including the Brazilian Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST), Argentina’s National Indigenous Peasant Movement, and Guatemala’s Peasant Unity Committee. Likewise, Francis’ discursive shift from the Church’s obsession with sexuality towards poverty or “the social” has been read by some as a vindication of liberation theology. On his previous Latin American tours, Francis has been able to capitalise on this approach by holding meetings with popular movements, peasants, and indigenous people, among others.

Pope Francis and Chilean social movements

But for a multitude of reasons the fervour generated in other latitudes was not replicated amongst Chilean social movements. Although this is an area that still requires further research, some hypotheses can be raised.

In other Latin American latitudes, it is possible to see connections and continuities between popular movements and Christian liberation movements during the second half of the 20th century. Yet, most of the social demands that have impacted on current political debates in Chile have been propelled by social movements that emerged after decades of depoliticisation and demobilisation. Most of these have lost the memory of a political past shared with ecclesiastical grassroots communities whose thinking was never in dialogue with liberation theology or other progressive faith-based projects.

Thus, if Francis’ words were read by some Latin American popular movements as acknowledging the sources that inspired their origins and religious motivations, they provoked a very different reaction amongst the most important social movements at play in the current Chilean political scenario.

Another hypothesis is related to the increased role of Chilean gender and sexuality politics in recent years – especially during the second government of president Bachelet (2014-2018) – and the antagonism this provoked with religious conservative activism, specifically the Catholic Church hierarchy.

The decriminalisation of abortion, the draft bill aiming to legally recognise self-perceived gender identity, the civil-union law, and the marriage-equality bill were all important components of the recent legislative agenda, often criticised by the Catholic hierarchy. But feminist and LGBTI movements have not hesitated to denounce the reactionary meddling of the Catholic Church in parliamentary debates.

Given this scenario, it was not easy for Francis to position himself as a legitimate voice for Chilean social movements: he leads an institution that has consistently favoured the polar opposite of the local activist agenda and whose domination of the country’s sexual politics has long been a target of political action.

It is true that Francis’ sexual politics have not been as severe as those of his predecessors. He has spoken of forgiving women who have undergone abortions and of not judging gay and lesbian people.

However, he has also dedicated himself to carefully guiding the interpretation of his words, locating them within the boundaries of the Church’s magisterium, which was jointly elaborated by John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Francis has also encouraged and elaborated a notion of “gender ideology” that has become fashionable in recent conservative strategies as a discursive tool to delegitimise feminist and LGBTI politics.

In this sense, the Pope’s ambivalence continues to be aligned with the opposition to sexual and reproductive rights that has for so long characterised the Vatican’s position.

Post-Francis Chile

Since his enthronement in 2013, the back-and-forth between conservative and more progressive positions has been central to Francis’ politics. The success of his style lies in the polysemy of his speeches, where one can find gestures to liberation theology as well as to the conservative sexual politics of his predecessors. In fact, Francis can serve as a device that permits multiple interpretations amongst a wide range of actors, with even those antagonistic to each other able to find pleasing answers in his words.

However, this ambivalence worked against him in Chile. Given the blatant institutional crisis of the Chilean Catholic Church, citizens expected drastic condemnation for the role played by the hierarchy in current sexual-abuse scandals. Instead, the Pope opted to play his traditional game of diffuse signals, which only ended up provoking condemnation of the Pope himself.

As such, the papal visit to Chile seems to have defined the limits of the “Francis phenomenon”.

The paradox is evident: in a historical moment when the leader of the Catholic Church is attempting to leave behind the centrality of the conservative sexual agenda of his predecessors, the abusive sexual practices of the Church’s hierarchy have obstructed Francis in distancing himself from these issues.

Unlike John Paul II and Benedict XVI, who insisted on their right to enquire into the sexuality of women and LGBTI communities, Francis now sits in the dock himself and has to demonstrate accountability for issues of sexuality within his own institution.

As we know, the media’s response to Francis’ (failed) visit in Chile was quite immediate. And once made aware of the detrimental effects of his final remarks before boarding the plane to Peru, the Pope tried to clarify (albeit ambiguously) his statement in defence of Barros. He then had to double down on this bet by appointing a Vatican representative to further investigate the allegations against Bishop Barros. In doing so, Francis finally seems to have understood that the issue of sex abuse jeopardises his leadership.

Rather than representing the exhaustion of the Pope’s model, what happened in Chile marks the limits of a particular phenomenon. Francis will most likely continue to use the discursive style that has given him his own political identity and allowed him to distance himself from his predecessors.

Yet, despite the air of renewal he aims to bring into the Church, the legitimacy of Catholicism continues to be eroded by its sexual politics.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This article is a lightly edited version of a piece that first appeared in Sexuality Policy Watch (SPW) and was republished by the LSE Engenderings blog

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting