The financial burden of violence for the Mexican economy will require a significant adjustment to the federal government’s internal security expenditure, irrespective of who wins the upcoming election, write Mohib Iqbal and José Luengo Cabrera (Institute for Economics and Peace).

The financial burden of violence for the Mexican economy will require a significant adjustment to the federal government’s internal security expenditure, irrespective of who wins the upcoming election, write Mohib Iqbal and José Luengo Cabrera (Institute for Economics and Peace).

Estimates from the 2018 Mexico Peace Index (MPI) show that the economic impact of violence in Mexico was 4.72 trillion pesos (US$249 billion) in 2017.

Equivalent to 21 per cent of Mexico’s GDP, violence imposes a hefty financial burden on the Mexican economy. At 33,118 pesos (US$ 1,757) per capita, the economic impact of violence is greater than four months of income for the average Mexican worker.

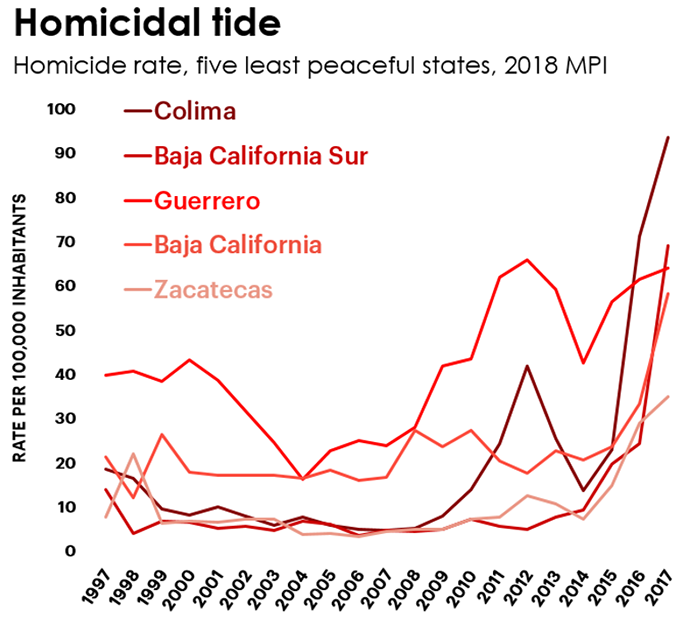

With 2017 marking the year with the highest homicide rate on record, questions have been raised about the Mexican authorities’ ability to curb the rising tide of violence.

This is particularly telling if we consider that the economic impact of violence increased by 15 per cent from 2016 to 2017. During the same period, the homicide rate rose by 22 per cent, whereas federal government expenditure on internal security contracted by ten per cent, suggesting a serious mismatch between the magnitude of violence and the resources allocated to prevent and contain it.

Mexico is the OECD country with the highest homicide rate, yet like Denmark it devotes the lowest share of GDP on public security: just one per cent. To address Mexico’s escalating violence will require an adjustment to the federal government’s internal security expenditure, irrespective of who wins the July 2018 Mexican general election.

Consequential vs containment costs

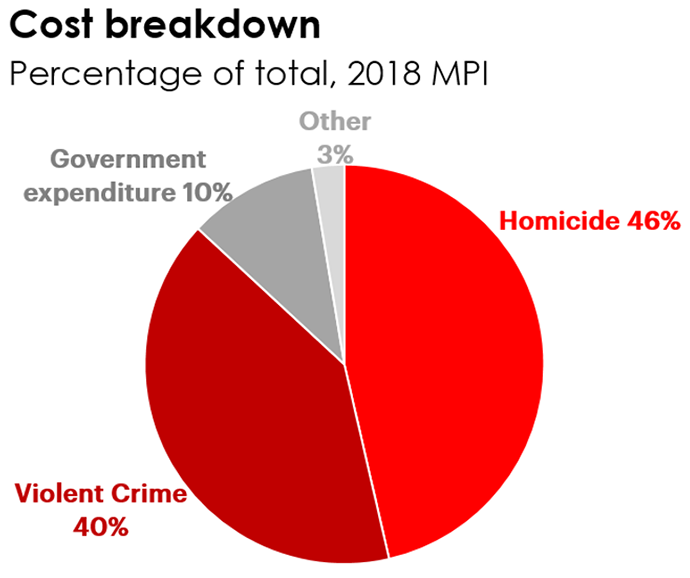

Homicide is responsible for the lion’s share of the economic impact of Mexican violence, accounting for 46 per cent of the total impact in 2017, up from 42 per cent in 2016. The total financial cost of homicide for the Mexican economy amounted to 2.18 trillion in 2017, equivalent to 10 per cent of Mexico’s GDP.

Violent crime – comprising robbery, assault, and rape – was the second most expensive form of violence, representing 40 per cent of the total economic impact of violence, at 1.9 trillion pesos.

Federal government expenditure on prevention and containment of violence – namely policing, the judiciary, and the armed forces – amounted to 493 billion pesos, or 10 per cent of the total economic impact. The remaining three per cent of economic losses include indicators that measure the fear of violence, organised crime, household firearm purchases, and the costs of private security.

Overall, homicide and violent crime represented 86 per cent of the economic impact of violence in 2017. This shows that the financial cost of violence was more than eight times federal government spending on its containment.

Opportunity cost

The costliness of violence also means that resources that could otherwise be put to more productive ends are drained by the unproductive consequences of violence. The economic impact of violence was, for example, seven times higher than the federal government’s expenditure on education and eight times higher than spending on health in 2017.

This significant financial trade-off also suggests that reducing the level of violence can be cost-effective. Indeed, estimates from the 2018 MPI show that reducing the economic impact of violence by just one per cent would free up the equivalent of the government’s expenditure on science, technology, and innovation in 2017.

With the rising trend in the level of homicides, particularly in the five least peaceful states of the 2018 MPI ranking, where homicide rates increased by an average of 63 per cent between 2016 and 2017, the incentive to adjust security expenditure derives from the financial benefits that could be reaped if violence were significantly reduced.

Peace dividend

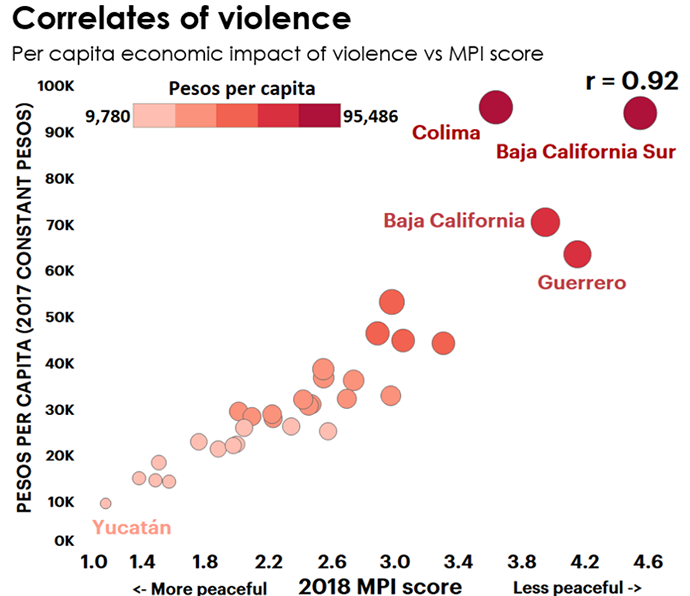

Results from the 2018 MPI report show that states with higher levels of peacefulness, as measured by the MPI overall score, registered the lowest per capita economic impact of violence. The correlation between these two measures is statistically significant.

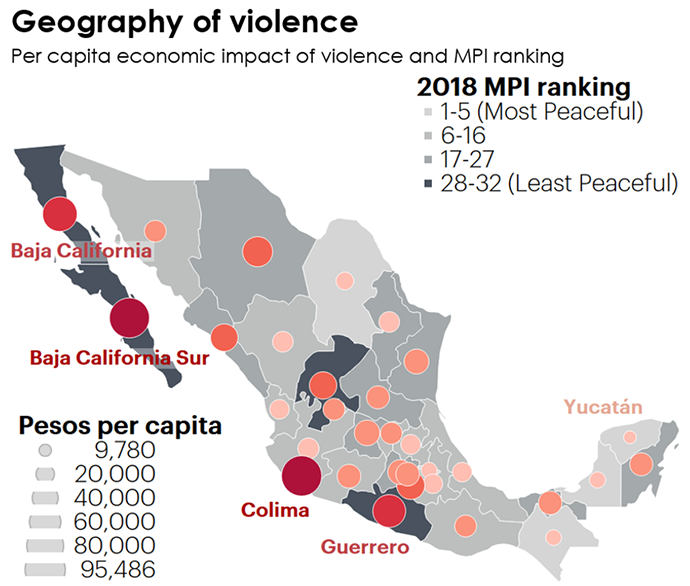

When looking at the geographic distribution of the economic impact of violence, four of the five least peaceful states in the 2018 MPI ranking – namely Baja California Sur, Guerrero, Baja California and Colima – registered the highest figures. These states are all located along the Pacific coast, where most of the country’s organised crime syndicates operate.

Colima, which ranked 29th out of 32 states in the 2018 MPI, registered the highest per capita impact at 95,486 pesos (US$ 5,292). This state registered the highest homicide rate in Mexico in 2017, at 93.61 cases per 100,000 people.

Yucatán, the most peaceful state in the 2018 MPI ranking, had the lowest per capita impact of any state at 9,779 pesos (US$ 542). Estimates from the 2018 MPI report show that if the level of peace in every state improved to Yucatan’s level, the economic impact of violence would be reduced from 4.7 trillion pesos (21 per cent of GDP) to 1.65 trillion pesos (nine per cent of GDP).

This is equivalent to a peace dividend of three trillion pesos, highlighting the potential benefits of lower levels of violence across the Mexican states, particularly the least peaceful ones.

Adjusting expenditure

If Mexico is to make progress in reducing its high level of violence and the associated costs, expenditure on violence containment needs to better reflect the magnitude of the problem.

Although the resourcing and effectiveness of Mexico’s public security agencies remains a contentious matter, and issues regarding the militarisation of public security are controversial, comparative statistics highlight the degree to which Mexico’s security expenditure is ill-adapted to the country’s level of violence.

To put things into perspective, Mexico’s homicide rate is the highest in the OECD but the country places at the bottom of the ranking for internal security expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

Mexico’s expenditure on internal security is just 60 per cent of the OECD average and, at less than one percent of its 2017 GDP, it is comparable to the levels of spending in Denmark and Luxembourg, whose homicide rates are 30 times lower than that of Mexico.

If Mexico is to reduce its high level of violence, expenditure will need a significant adjustment. For its part, the federal government’s internal security expenditure has so far been insufficient to halt a steep rise in the homicide rates, which last year reached record highs.

The outlook for 2018 is already looking bleak, as the first three months of this year have also been marked by record homicide rates. A total of 7,666 people murdered is equivalent to 85 homicide victims per day, or nearly four murders per hour. This is 12 per cent higher than the rate at the same time last year, and 66 per cent higher than the first trimester of 2015.

Given that investing in violence containment can be cost-effective, adjusting internal security expenditure to the rising tide of violence represents a clear and pressing policy challenge.

With this year’s hotly contested polls looming, the growing political salience of Mexican insecurity will no doubt require the next administration to make significant adjustments to its security policy.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting