Mexico has a long history of discretionary application of the law, as demonstrated recently by the government’s failure to prosecute corrupt state governors while they remained in office. Even from their position of political strength, Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his Morena party may find it hard to revert this trend and make good on their promise to root out corruption, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

On 10 January 1989, just a month after President Carlos Salinas de Gortari had taken office, soldiers armed with bazookas raided the residence of Joaquín Hernández Galicia, better known as “La Quina”.

La Quina was one of the most powerful men in Mexico, having risen risen through the ranks of Mexico’s gargantuan oil union, the STPRM, where he established a veritable fiefdom from his base in Tampico, Tamaulipas. He was the archetypal strongman during the 70-year rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), controlling not just the union but also the local political establishment, the local police and courts, and the local media. Practically no decision of political or economic importance in north-east Mexico was taken without his approval.

Unfortunately for La Quina, his old nationalist views came into conflict with the free-market policies that Salinas had promised to pursue in the wake of the “lost decade” of the 1980s. Salinas, who won a 1988 election marred by fraud, needed to show the country who was the real boss of bosses. And so La Quina was arrested and sentenced to 35 years in jail for possession of weapons, rather than for the more obvious charge of corruption.

Although he served less than a decade before being absolved and released in 1997, his reign was all but over. The oil union came under the control of new feudal lords, but none have ever wielded the same power that La Quina did in his heyday.

Since La Quina’s shocking arrest, Mexican presidents have not hesitated to stage bold displays of authority shortly after taking office. Felipe Calderon, whose election was also marred by claims of fraud, launched the drug war just days after becoming president. Current president Enrique Peña Nieto came close to repeating the “Quinazo” in arresting the powerful teachers’ union boss Elba Esther Gordillo in February 2013.

Yet what these incidents have shown is not so much the ruthlessness with which the Mexican state can act against its most corrupt and criminal elements, but rather that it only does so at its own discretion. The strongest – if not only – predictor of whether a major political figure in Mexico will face justice is whether he or she falls foul of the establishment, namely the president or the ruling party. The severity and conspicuousness of their crimes is secondary.

A tale of 22 governors

Nothing illustrates the discretionary nature of the rule of law in Mexico more clearly than the stories of the myriad state governors arrested in recent years.

The Peña Nieto government has at times tried to claim credit for arrests on its watch. But in almost all cases, authorities long ignored signs of gross misconduct. And in the most egregious cases, they did little to prevent disgraced governors from fleeing the country.

By far the most notorious case was Veracruz’s Javier Duarte (2010-16), who is accused not only of personal enrichment but also of illegally funnelling millions from state coffers into Peña Nieto’s 2012 campaign. Despite being an obvious flight risk, he and his wife fled Mexico with relative ease; he was ultimately tracked down in Guatemala. His wife remains at large, but she is believed to be living a lavish yet discreet lifestyle in one of London’s more upscale neighbourhoods.

Javier Duarte was unlucky, as was Roberto Borge (2011-16) of Quintana Roo, arrested in Panama just before boarding a plane to Paris. In contrast, Chihuahua’s Cesar Duarte (2010-16) also went on the run, but he has yet to be found.

Under Peña Nieto alone, a total of 22 governors have been arrested or investigated for embezzlement or other misdeeds, including links to organised crime. But none of them faced any legal action while in office.

Applying the rule of law to sitting officials is complicated by the fuero, a type of constitutionally granted immunity that many civil society organisations and NGOs would like to see reformed or removed altogether. One reform proposal did pass through the lower house in August 2017, but it was subsequently torpedoed in the Senate.

But blaming inaction on the fuero ignores the power that political parties have over their members. It’s hard to imagine, for example, that Veracruz’s PRI-dominated state congress would have defied pressure by Peña Nieto and the PRI’s national leadership to strip Duarte of his fuero while he was still in power.

As powerful as state governments have become since the end of one-party rule in 2000, they are still subject to the power of the presidency and the ruling party. The issue is that the president and his party seem only to act when their reputation is at stake.

Morena’s challenge

As the prominent Mexican security expert Alejandro Hope once stated: “the return of the PRI to power provided a license to steal, or at least it was interpreted as such by many ex-governors”.

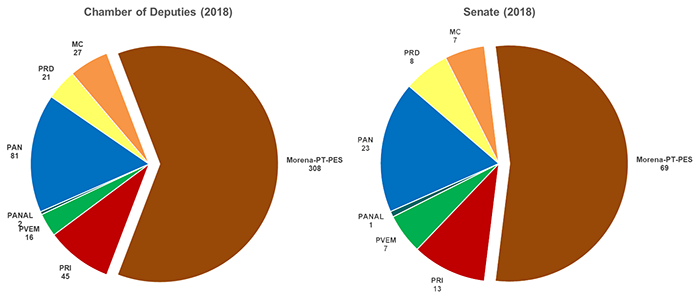

The challenge for the incoming administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador will be to use the considerable resources at its disposal to tackle corruption full-on, especially considering that AMLO’s landslide victory in July 2018 was largely due to public outrage over rampant corruption and his promise to end it.

The first problem is that his party, Morena, has no shortage of morally dubious characters in its ranks, many of them former PRI-istas who have jumped that sinking ship to further their political careers. And while López Obrador has certainly proposed many innovative polices to “transform” Mexico, it is not clear that Morena really represents a different way of doing politics.

As such, it will once again boil down to the administration’s will to tackle the establishment’s rogue elements. López Obrador has promised that he will satisfy the public clamour for justice, but this has been contradicted somewhat by statements that appear to favour some form of amnesty for those accused of corruption as a means of wiping the slate clean when he takes office.

On the plus side, AMLO’s administration will have more weapons with which to combat corruption than its predecessors did, as well as the ability to forge new ones through Morena’s control of Congress.

Some of these weapons remain blunt, however. The “anti-corruption system” passed in 2015, for instance, continues to lack one of its main components: an anti-corruption prosecutor. Mexico has also been slow to address links between private- and public-sector corruption. It ranks, for example, alongside Venezuela as the only country yet to have prosecuted anyone as a result of the region-wide Odebrecht scandal.

If López Obrador’s promise of severing the links between political and economic power is to be believed, it must start with a recognition that private corruption in Mexico runs just as deep.

The Mexican disease

Some “Quinazos” prove to be more enduring than others. In early August, Elba Esther Gordillo was released from house arrest after charges of money laundering and organised crime were dropped. What began as the latest use of state power to smother a powerful political rival ended in humiliation as public prosecutors were unable to make the case against her hold up.

To many Mexicans, her release shows that even the power of the Mexican presidency has its limits. But that being the case, will the desire to go up against powerful political or economic interests be enough to cure the country’s longstanding ills of corruption and impunity? To make matters worse, there are fears that Duarte might also be set free in circumstances surprisingly similar to those of Gordillo.

This in mind, it is not especially reassuring to recall the memorable phrase of López Obrador’s political idol, the 19th century liberal hero Benito Juárez: “To my friends, justice and reward. To my enemies, the law.”

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting