Since Panama established diplomatic relations with China in June 2017, the two countries have developed an incredibly strong relationship. Only geostrategic sensitivities relating to the trade war between China and the US have prevented the two countries from announcing the conclusion (in record time) of a bilateral free trade agreement. But it is now a matter of when not if, and China’s efforts to draw Latin America and the Caribbean into its Belt and Road Initiative continue apace, writes Álvaro Méndez (LSE Global South Unit).

Since Panama established diplomatic relations with China in June 2017, the two countries have developed an incredibly strong relationship. Only geostrategic sensitivities relating to the trade war between China and the US have prevented the two countries from announcing the conclusion (in record time) of a bilateral free trade agreement. But it is now a matter of when not if, and China’s efforts to draw Latin America and the Caribbean into its Belt and Road Initiative continue apace, writes Álvaro Méndez (LSE Global South Unit).

China’s President Xi Jinping has just completed his fourth tour of Latin America with a historic two-day state visit to Panama, which Beijing sees as the future hub of its Latin American trade nexus.

Panama is a very small state with a very strategic Canal. It is the prime locus where the twin prongs of China’s global strategy synchronise and synergise. Beijing approaches Panama itself as a peer in its club of developing countries, a kind of grand coalition of the global periphery. The unmistakable implication for the USA, China’s main rival for global hegemony, is that the writing is on the wall for its longstanding dominance.

A recent opinion piece by the Economist Intelligence Unit argued that China’s advance into Latin America is not driven by geopolitical strategic objectives but by economic factors. However, the evidence contradicts this conclusion. The importance that China attaches to its geostrategic relationship with Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) has become ever more noticeable since Xi Jinping came to office in 2013.

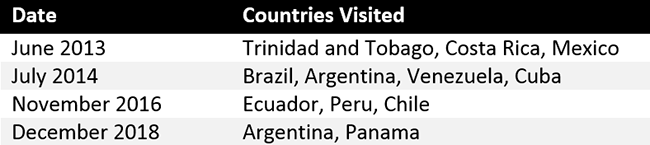

His first visit to the USA came only a tour of other parts of the Americas, with official state visits to Trinidad and Tobago, Costa Rica, and Mexico. Analysts interpreted this as anything from a reordering of priorities to a direct snub of Washington. After just five years in office Xi has already visited 12 LAC countries (see Table 1, below), which is more than have been visited during the ten years of the Obama and Trump administrations.

Panama and China: a rapidly developing special relationship

Before 2017 Panama had no diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), but the situation changed dramatically in June of that year when Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela suddenly severed relations with Taiwan and recognised the PRC instead. A historic state visit to China by President Varela immediately followed in November 2017.

The thirteen months since that visit have yielded more progress in China-Panama relations than other Latin American countries had managed over many years of diplomacy. By July 2018, Panama had signed an astonishing battery of 28 bilateral agreements with Beijing, covering everything from free trade to infrastructure development, from tourism to cultural exchange. But Xi’s most recent visit in early December 2018 suggests that this was only the beginning, as another 19 new agreements have just been announced.

This gamut of agreements reveals an ambitious bilateral agenda that shows a great deal of agency and leadership on the Panamanian side, while also epitomising China’s efforts to recruit the Global South, including Panama, into its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beijing has stated that this global strategy “to achieve manifold economic and political ends” already has the support of 14 LAC countries and 122 countries globally.

As the first country in the region to sign China’s template Memorandum of Understanding “on Cooperation in the Framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative”, Panama has made itself a fundamental part of this strategy. A bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) would surely facilitate this development, and indeed a Panama-China FTA will arrive far sooner than anyone expected.

A free trade agreement in record time?

As President Varela himself told me earlier this year during a visit to LSE, his goal was “to advance as much as [he could] the treaty for the [anticipated] visit” of Xi Jinping, which did ultimately take place in early December 2018. Other conversations with government officials and top policy makers also strongly suggest that the original intent of this historic visit was to announce the conclusion of a Panama-China bilateral FTA.

As the timeline below shows, the pace of the negotiations towards this agreement could well have set a world record, with rounds happening in every month but one between July and November 2018 in order to be ready for Xi’s visit:

- 13 June 2017 – Panama and China established diplomatic ties

- 17 September 2017 – Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Panama

- 14-21 November 2017 – President Varela goes to China for a state visit

- 17 November 2017 – MoU to do feasibility study for the Panama-China FTA is signed

- 7 December 2017 – Chinese Minister of Commerce visits Panama to discuss FTA

- 16 January 2018 – Feasibility study for the FTA starts

- 3 March 2018 – Feasibility Study for the FTA concludes with positive results

- 24 May 2018 – Chief Negotiator for the Panamanian side is appointed

- 9-13 July 2018 – First Round of negotiations takes place in Panama City

- 20-24 August 2018 – Second Round of negotiations takes place in Beijing

- 9-13 October 2018 – Third Round of negotiations takes place in Panama City

- 19-23 November 2018 – Fourth Round of negotiations takes place in Panama City

- 19 November 2018 – Panama announces “additional” rounds of negotiation are needed

- 2-3 December 2018 – First official state visit to Panama by Xi Jinping

It was precisely because of geopolitical considerations rather than economic ones that the announcement of a bilateral FTA was delayed.

First, it would have exacerbated the current trade crisis between the US and China, particularly coming hot on the heels of 90-day truce agreed between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping at the recent G20 in Buenos Aires.

Second, it would have set alarm bells ringing in Washington: as recently as October 2018 the US warned Panama against doing business with China on such a massive scale. According to a senior former official of the State Department, the worry was that the announcement of an FTA could be perceived as an insult by the Trump administration, which could react by limiting or abrogating the US-Panama FTA in place since 2007.

Third, Beijing also seems slightly hesitant to sign an FTA with a country that also has one with Taiwan. This agreement entered into force in January 2004, but to date Varela has been unable to rescind it due to Taipei’s insistence on its continuing validity.

The Panama-China FTA: not if, but when

The FTA is nonetheless imminent, with the national interest of both countries driving a determined push towards conclusion.

With a total of 47 bilateral agreements already agreed in just eighteen months, the FTA would represent significant progress towards China’s goal of making Panama the hub of its Latin American trade network. Former US Ambassador to Panama John Feeley believes that Beijing sees “in Panama what [Washington] saw in Panama throughout the 20th century; a maritime and aviation logistics hub”. For Panama, meanwhile, the FTA would provide the opportunity to “attract large-scale Chinese investments, supporting Panama’s ambitious growth and development agenda”. The personal prestige of both leaders is also on the line, meaning that they are fully committed to seeing it through on their own watch.

On the Chinese side, President Xi has committed his administration to China’s relationship with Latin America, yet he has yet to conclude an FTA with any country in the LAC region. There are currently three FTAs in place (Chile, Peru, and Costa Rica), but these were signed by his predecessor Hu Jintao.

On the Panamanian side, the desire is even stronger. President Varela is determined to close the deal before he leaves office on 1 July 2019. The growing economic and political importance of China in Latin America has made it a prestigious and coveted achievement to negotiate an FTA with Beijing.

The short-termism of Latin American politics tends to have a knock on effect on states’ foreign policy establishments, meaning that countries need to initiate and conclude trade agreements within single presidential terms which are usually no more than 4-5 years. In the case of China, only three major political figures in LAC have ever managed to pull it off: Ricardo Lagos of Chile, Alan Garcia of Peru, and Oscar Arias of Costa Rica. Each of these presidents still believes that signing and ratifying an FTA with China was one of the most important achievements of their tenure, if not the most.

The Constitution of Panama empowers the President of the Republic to “direct foreign policy, to negotiate treaties and conventions, which will then be submitted for consideration by the legislative body”. Varela is hoping that this responsibility will provide the crowning achievement of his presidency: the triple trade-policy success of FTAs with South Korea, Israel, and especially China.

The former two are already signed but still await submission to the legislature for ratification. The President’s strategy is to present all three FTAs as a package deal, the better to shepherd them unscathed through the Panamanian National Assembly. This is a shrewd strategy, as the seriousness of voting down all three deals at once could well cow opponents into supporting ratification. This kind of opposition is in any case unlikely given the potential benefits of becoming China’s gateway to Latin America, but for the same reason Varela will not be taking any chances.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting