Coca cultivation in Colombia has risen dramatically in recent years, leading the Colombian government to consider a return to aerial-spraying campaigns previously halted over health concerns. But former president Juan Manuel Santos suggests that factors other than a suspension of spraying were to blame, not least a reconfiguration of non-FARC armed groups and the perverse incentive of a future crop-substitution programme announced early on in the peace process. Analysis of temporal variations created by this announcement and geographical variations relating to coca suitability and possible benefits from the substitution initiative suggest that Santos may be correct, write Daniel Mejía (Universidad de los Andes), Mounu Prem (Universidad del Rosario) and Juan Vargas (Universidad del Rosario).

• Disponible también en español

According to figures from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2017 the extent of coca cultivation in Colombia reached a record high of 171,000 hectares. This figure has risen consistently since 2013 and represents almost a fourfold increase over that period.

This steep rise set alarm bells ringing in Washington. On May 2017, during an official visit by then president Juan Manuel Santos, the White House expressed its concerns, and a month later the US Secretary of State asked Colombia to resume aerial coca-spraying campaigns. Four months later, President Trump threatened to decertify Colombia in the fight against illegal drugs due to the extraordinary spread of illicit-crop cultivation.

Why the recent rise in Colombian coca cultivation?

This has led in turn to a reopening of debates on aerial spraying of illicit crops with glyphosate, a practice suspended in 2015 on the grounds that this herbicide was “probably carcinogenic” according to the medical literature. In 2017, however, the Constitutional Court indicated that the National Narcotics Council could reverse its position on glyphosate if specific guidelines were met to minimise its impacts on health, and under President Iván Duque there has been a shift towards seeing aerial spraying as a possible solution to the recent spike in coca cultivation.

But was suspension of aerial spraying responsible for the rise in the first place? Here there is significant disagreement between Duque and his predecessor Santos.

At a public hearing on the issue in March 2019, Santos dismissed the view that suspension of aerial spraying was to blame. There were, he said, four other key factors:

- Devaluation of the peso, which increased the profitability of drug trafficking

- Falling gold prices, which decreased the opportunity cost of cultivating coca

- Repositioning of criminal gangs in areas previously controlled by FARC guerrillas

- Early announcement of an incentive programme for switching from coca to legal crops

Our recent research confirms that on these third and fourth points in particular, Santos was absolutely right.

Crop substitution: an incentive for peace?

The peace process between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP officially started in October 2012. One of the most important achievements of the process prior to the signing of the final agreement in 2016 was a partial agreement on the issue of illicit drugs.

On 16 May, 2014, the government and FARC delegations announced that there would ultimately be a Comprehensive National Programme for the Substitution of Crops for Illicit Use “in order to generate the material and intangible conditions for well-being and good living amongst populations affected by crops for illicit use, in particular for rural communities in situations of poverty that currently derive their subsistence from these crops.”

Crucially, the words “material conditions” created the possibility that farmers would expect to receive direct monetary transfers in exchange for voluntary substitution of illegal crops.

Anticipation effects and warped incentives

Whether or not the early announcement of a future crop-substitution programme contributed to the recent rise in coca cultivation is an empirical question that can be tackled by exploiting the temporal variation related to the announcement and two particular sources of geographical variation.

The first of these is a measure of the ease of growing coca based on municipality-level climatic and ecological characteristics. This measure accounts for the relative cost advantage of growing coca in a given municipality.

The second source of spatial variation comes from the expected benefit of growing coca if the proposed substitution programme were to be implemented. In particular, the statement anticipated that areas with existing coca cultivation and a high incidence of poverty would be targeted. Using these two variables at the municipal level we build a measure of the expected probability of benefiting from the substitution programme.

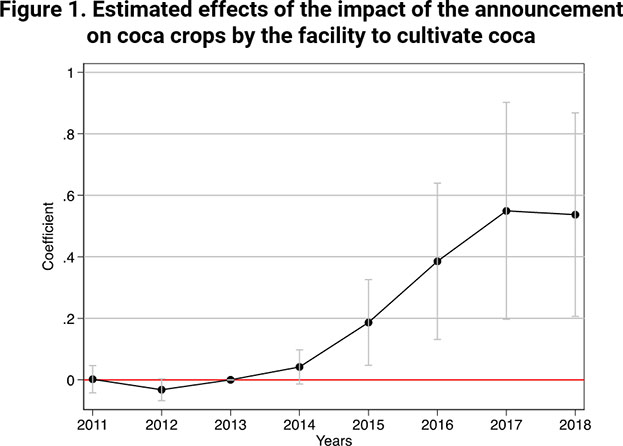

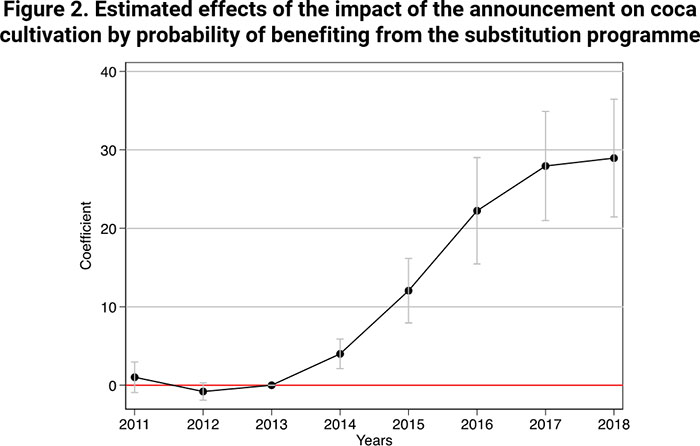

When we combine the temporal variation given by the announcement, first, with geographical variations in the ease of growing coca (figure 1, below) and, second, with municipal-level differences in expectations of benefiting from crop-substitution incentives (figure 2, below), two important observations can be made.

First, prior to the announcement there was no difference in coca-crop coverage in municipalities with high- or low-suitability conditions or with high or low estimated probability of benefiting from the proposed substitution programme.

Second, since the year of the announcement (made in May, 2014), there is a permanent differential increase in coca cultivation in municipalities with lower relative costs of growing coca (figure 1) and those with higher expected benefits (figure 2).

Substitution, cultivation, and aerial spraying

Before considering the implications of these findings, it is important to emphasise that our research makes no attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of the substitution programme itself. Indeed, by mid-2019 more than 100,000 families had enrolled in the new programme, resulting in eradication of over 30,000 hectares of coca, and this with extremely low levels of recidivism.

That said, our estimates regarding anticipation of the programme show a large increase in coca cultivation in municipalities where the announcement found most resonance (due to greater ease of growing or stronger expectations of benefiting). An increase of one standard deviation in the coca-suitability index generates a differential increase of 100 per cent in coca cultivation after the announcement. We also estimate that an increase of just 10 per cent in the expected probability of benefiting from the programme generates a 51 per cent increase in coca-cultivation levels.

This increase is persistent over time, extending even beyond the start of the substitution programme’s implementation. Persistence is also associated with violence by other (non-FARC) armed groups attempting to control coca crops new and old, a result that supports the third explanation for rising coca cultivation offered by Juan Manuel Santos in March, 2019.

Another crucial finding is the recent rise in coca cultivation is not associated with the suspension of aerial spraying. Once we control for the interaction between the magnitude of aerial spraying before its suspension and time-fixed effects, the estimated effects of the coca-suitability index and predicted benefit remain intact. With Colombia recently considering a return to aerial spraying, this finding should be borne in mind by policymakers as they shape the future of drug policy.

The increase in coca cultivation also occurs in protected areas such as national parks and indigenous reserves, albeit to a lesser degree. This is important for two reasons.

First, it shows that cultivation increased even in areas where aerial spraying was forbidden long before May 2014, which further supports our earlier finding on the relative irrelevance of spraying. Second, the fact that the increase in coca cultivation is smaller in areas where aerial spraying was already forbidden suggests that greater state presence and state capacity can have a mitigating effect when it comes to reducing illegal activities, even given the perverse incentives generated by the announcement. This is important in terms of public policy.

The ongoing debate about the increase in illicit-crop cultivation in Colombia and the role of manual eradication, aerial spraying, and substitution programmes could benefit greatly from further rigorous studies that evaluate respective impacts and costs. These studies could in turn feed into the design and implementation of better public policies.

Although our results suggest that the announcement of a future crop-substitution initiative had a perverse effect on coca cultivation, the challenge now is to identify and implement programmes that provide the right incentives. It is also important to strengthen the presence of the state across Colombia’s territory in order to prevent armed groups not included in the peace agreement from exploiting illegal crops while curbing efforts at eradication and substitution.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This post draws on the authors’ paper The Rise and Persistence of Illegal Crops: Evidence from a Naive Policy Announcement (2019)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting