LSE’s Alex Free profiles Jomo Kenyatta – the first president of Kenya and an LSE graduate who came to London and studied social anthropology under Bronisław Malinowski in the 1930s. A leading pan-Africanist with an ultimately mixed political legacy in office, Kenyatta produced his famous ethnographic study of the Kikuyu, Facing Mount Kenya, while at LSE.

Jomo Kenyatta is a fascinating figure in African, world and LSE history. Perhaps especially in his formative years, he was a champion of anti-colonialism, African nationalism, pan-Africanism and the unity of all peoples of African descent around the world. Along with other leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Patrice Lumumba (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), Kenyatta belonged to a highly influential generation of post-independence “fathers” of African countries. Taking office as the first prime minister of Kenya in 1963 (and becoming president in 1964), he oversaw the country’s transition from a former British colonial possession to an independent country over 18 years in office.

In the period immediately preceding decolonisation, Kenyatta was a leading figure in the call for independence from Great Britain as president of the Kenya Africa Union (KAU). Kenyatta was a member of the Kikuyu – the largest ethnic group in Kenya – and came to command a loyal following in central Kenya at this time. He was also at pains to secure a broad base of support across the country, in a bid to calm latent fears of the dominance of any particular group following the hoped-for achievement of independence.

![By National Archives of Malawi (National Archives of Malawi) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsehistory/files/2017/09/Jomo_Kenyatta_escorts_Dr_Banda_at_the_end_of_the_latters_visit_cropped.jpg)

LSE, London and Britain

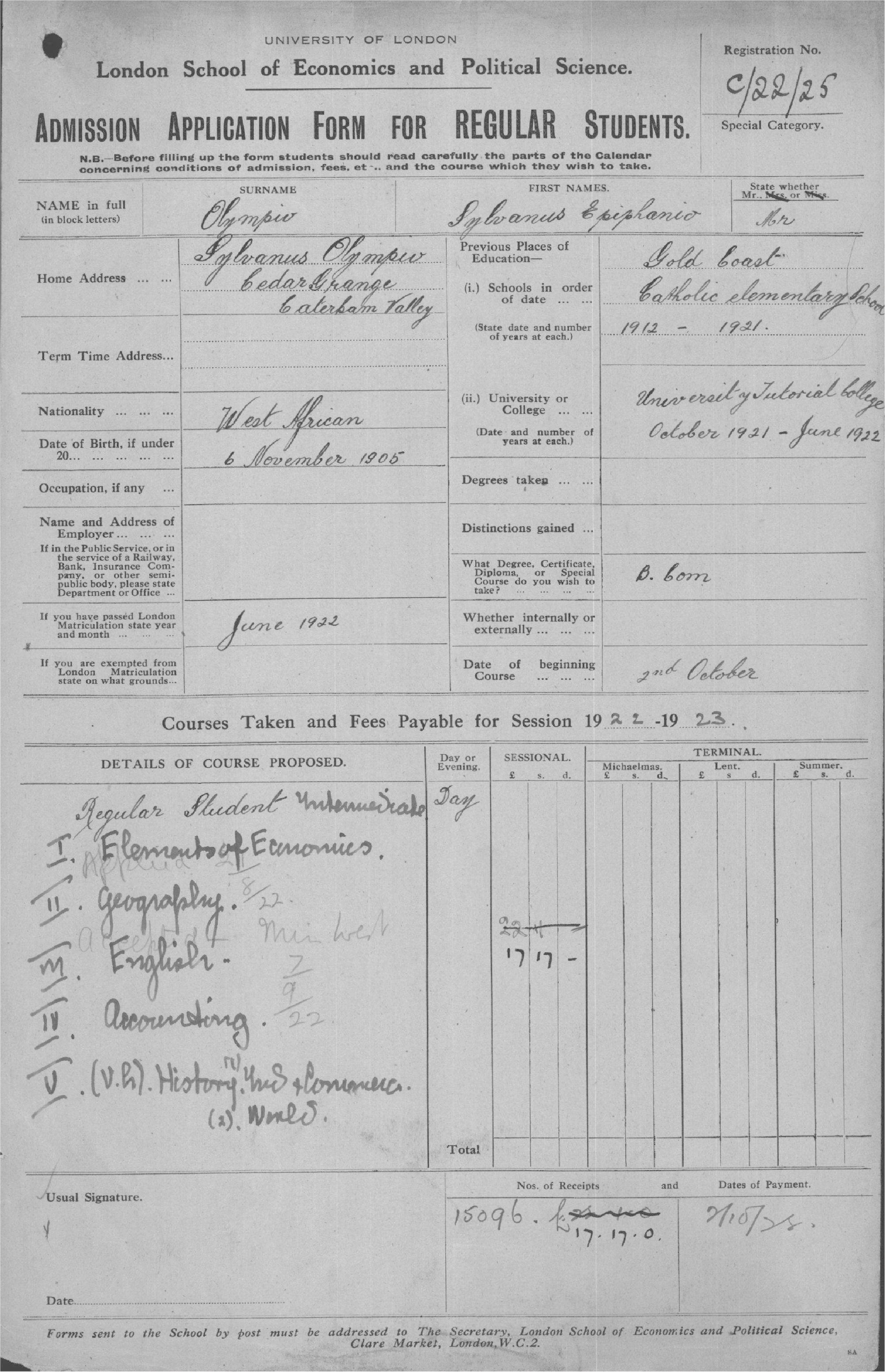

LSE, London and Britain in general provided the backdrop for many of Kenyatta’s important formative years in the run-up to the tumultuous independence period in Kenya. He first arrived in Britain in February 1929 and, having met with communist activists in London, spent several months in Moscow later that year, becoming strongly influenced by the policies and practices of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, by the time he was in office, Kenyatta’s previous enthusiasm for communism had markedly abated, and his economic policies were predominantly capitalist.

Kenyatta went back to Kenya in 1930, but returned to Europe in May 1931, spending the next 15 years away from East Africa. After a period of work and study at UCL (University College London) and SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), Kenyatta became a student of social anthropology at LSE, where he developed a strong relationship with his tutor, Bronisław Malinowski – the world-famous and pioneering anthropologist.

As a contrast to the work of other anthropologists and notable students of Malinowski – such as Audrey Richards and EE Evans-Pritchard – who studied groups of people as outsiders, the first-hand perspective that informed Kenyatta’s ethnographic work on the Kikuyu was immensely appealing to his tutor.

Facing Mount Kenya

Published in September 1938, Kenyatta’s study of Kikuyu life and customs, Facing Mount Kenya, received lavish acclaim from Malinowski, who was reputedly economical with praise and far from easy to impress. In the preface to the book (Kenyatta 1938: xiii–xiv), Malinowski recognised Kenyatta’s work as “one of the first really competent and instructive contributions to African ethnography by a scholar of pure African parentage”.

Producing Facing Mount Kenya enabled Kenyatta to demonstrate the order and sophistication of Kikuyu society and history. In combining the ‘objective science’ of social anthropology with the knowledge of a community insider, the publication of Facing Mount Kenya affirmed Kenyatta’s intellectual credentials and bolstered his authority to speak as a representative of the Kikuyu.

Consequently, in enabling Kenyatta to disrupt the epistemological foundations of the British colonial project as axiomatically “civilising” and thus “legitimate”, the study was both a feted scholarly tome and an important political device. As Jeremy Murray-Brown (1972: 189) argued: “In anthropology Kenyatta had found the weapon he needed to answer the philosophy of colonialism. The outcome was his book … Facing Mount Kenya.”

Kenyatta at LSE

Owing to its prestige, studying at LSE provided Kenyatta with enhanced gravitas among people in Britain and Kenya alike – albeit at a time when the School “was widely regarded as dangerously ‘pink’ and progressive” (Berman and Lonsdale 1998: 30), in contrast to the reputation that is likely to predominate today. As Bruce J Berman and John M Lonsdale (1998: 30) note: “To study at the famous LSE would raise his status among his fellow colonial students as well as in Kenya; enable him to deal as an equal with the colonial authorities, no longer a ‘semi-educated native’; and show the pervasive racism of the era…”

During his time in London, Kenyatta was an extroverted character who “liked being at the centre of life” (Murray-Brown 1972: 184). The journalist and broadcaster Elspeth Huxley – a fellow student at LSE – wrote that Kenyatta “was one of Dr Malinowski’s brightest pupils … A showman to his finger tips [sic]; jovial, a good companion, shrewd, fluent, quick, devious, subtle, flesh pot loving” (Murray-Brown 1972: 189).

While living in a students’ hostel in 1934, Kenyatta was offered the opportunity to appear as an extra in Zoltán Korda’s film Sanders of the River – set in British colonial Nigeria and starring the famous American actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson.

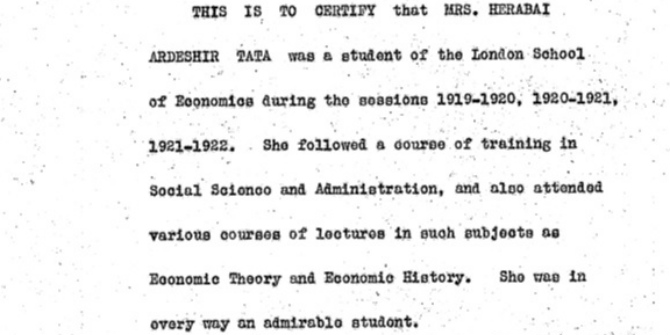

The film subsequently gave rise to controversy and criticism for its infantilising of “noble savages” and unquestioning celebration of Britain’s empire-building, but the contact between Kenyatta and Robeson developed into an enthusiastic friendship, enabling Kenyatta to regale Robeson with accounts of his experiences in colonial Kenya and Russia. In common with Kenyatta, Paul Robeson’s wife Eslanda Robeson – the anti-racism and feminist activist – was also a student at LSE in the 1930s.

Kenyatta’s legacy

While his importance as a prominent African nationalist and independence thinker is widely acknowledged, Kenyatta’s political legacy was mixed. As Simon Gikandi (2000: 4) notes, Kenyatta’s period in power was characterised by one-party dictatorship, cronyism and the politicising of ethnicity, and he and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah “are remembered both for making the dream of African independence a reality and for their invention of postcolonial authoritarianism”.

Following his death on 22 August 1978, Kenyatta was succeeded by his vice-president, Daniel arap Moi – whose 24 years in power were beset with consistent allegations of wide-scale corruption, bribery and human rights abuses. LSE is also connected to Moi’s successor, Mwai Kibaki, who studied for a BSc in public finance at the School, later becoming Kenya’s third president from 2002 to 2013.

References

Anderson, D (2005). Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. London: Phoenix

Berman, B J and Lonsdale, J M (1998). “The labors of ‘Muigwithania’: Jomo Kenyatta as author, 1928-45”. Research in African Literatures, 29(1), pp 16-42

Elkins, C (2005). Britain’s Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya. London: Pimlico

Gikandi, S (2000). “Pan-Africanism and cosmopolitanism: the case of Jomo Kenyatta”. English Studies in Africa, 43(1), pp 3-27

Kenyatta J (1938). Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. London: Mercury Books

Murray-Brown, J (1972). Kenyatta. London: G. Allen & Unwin

Browse more LSE History Blog posts from the Anthropology collection