Melanie Simms is an expert on industrial relations and has written prolifically on the topics of employment relations, trade-union organisation, identity and management. Melanie reflects on how the book Industrial Democracy by LSE founders Sidney and Beatrice Webb made her a better social scientist and a more impassioned campaigner. She also considers how the Webbs might view the improvements to the industrial sector since they lobbied for labour reforms at the turn of the 20th century.

Melanie Simms is an expert on industrial relations and has written prolifically on the topics of employment relations, trade-union organisation, identity and management. Melanie reflects on how the book Industrial Democracy by LSE founders Sidney and Beatrice Webb made her a better social scientist and a more impassioned campaigner. She also considers how the Webbs might view the improvements to the industrial sector since they lobbied for labour reforms at the turn of the 20th century.

The invitation to contribute to this blog from the LSE was a fantastic opportunity to re-read Industrial Democracy by Sidney and Beatrice Webb. I hadn’t read the book since I was a postgraduate studying at the University of Warwick for my MA in Comparative Industrial Relations in the mid-1990s. Since then, I have progressed through an academic career and, after deviations into interesting roles and research questions, now teach on the programme I on which I was then studying.

What strikes me most on reading the introduction to Industrial Democracy is how similar the Webbs’ research interests are to my own. They were engaged in applying robust social science methods to the political and economic questions of the day in an effort to build and test social theory. And they are social scientists who use their passion and empathy to ask important questions about the social world around them. The specific questions they ask are still the ones with which my work engages. How can working people gain more of a say over their lives both inside and outside work? What are the objectives of the organisations and institutions that developed to represent them? And how do those organisations and institutions reconcile, build and give voice to collective interests to achieve those objectives?

What strikes me most on reading the introduction to Industrial Democracy is how similar the Webbs’ research interests are to my own. They were engaged in applying robust social science methods to the political and economic questions of the day in an effort to build and test social theory. And they are social scientists who use their passion and empathy to ask important questions about the social world around them. The specific questions they ask are still the ones with which my work engages. How can working people gain more of a say over their lives both inside and outside work? What are the objectives of the organisations and institutions that developed to represent them? And how do those organisations and institutions reconcile, build and give voice to collective interests to achieve those objectives?

In this book, the Webbs use documentary data, observation and interviews to unpick the complex and political worlds of trade unions. The first edition was published in 1897 just two years after the Webbs had successfully persuaded the Fabian Society to use a recent bequest to establish a new university in London: the London School of Economics and Political Science. They had no respect for artificial boundaries between academia and campaigning. They wanted to be at the cutting edge of both and in a re-written introduction to the second edition published in 1902, they argue emphatically for the value of operating in both worlds.

Even at the time, they were criticized for being bourgeois do-gooders. But their contributions as social scientists cannot be under-estimated and Industrial Democracy is undoubtedly academically rigorous. They established the field that I now study and they made a strong case that policy interventions designed to help address social issues must be informed both by an appropriate understanding of the problem as well as robust evidence about the effectiveness of particular “solutions”. They made a strong case for the boundaries between practice and theory to be broken down to make each stronger. Industrial Democracy is amongst the very first writings to explore trade unionism and collective bargaining (a term coined by Beatrice Webb) as important economic, political and social phenomena.

Of course, they were writing in a very different context from that of contemporary academia and social policy. But I was inspired by the argument that not only could social science be informed by passionate political beliefs, but that those views could make us better social scientists as long as we are always willing to being led by evidence. They make such a strong case that undertaking good social science is an inherently political act because it requires us to ask some of the most difficult and most interesting questions about the world around us. I could not help but embrace their perspective which has informed my research, writing, teaching and practice ever since.

That was the inspiration about ‘what kind’ of academic I wanted to be. And it is only re-reading Industrial Democracy that I realize the extent to which the influence of their method, style and argument can also be seen in my contemporary studies of these subjects. The writing about the details of how trade unions balance democratic decision making with some degree of strategic direction is delicately written and demonstrates sophisticated insight into complex social processes. The themes they identify appear and re-appear in much of my own writing – although often with different conclusions. And little has changed in relation to the fundamental tensions within trade unions and similar organisations in the 100 years in between.

The real difference, of course, is the industrial and political context. At the time the Webbs were writing, general trade unionism for unskilled workers was only just being established. There were fewer than 2 million union members (around 10% of the workforce), the political and legal contexts were challenging, and victories for working people were few and far between.

Today, trade unions have somewhere around 6 million members (around 25% of the workforce) and although the political and legal contexts are still challenging, the right to freedom of association and free collective bargaining are labour standards enforced by the International Labour Organisation, a branch of the United Nations.

Principles such as strict regulation of child labour, a 40 hour basic working week, a national minimum wage, anti-discrimination legislation and rights to holiday, weekends and other paid rest periods are all deeply embedded within our working lives in this country. I think the Webbs would have been pretty impressed by some of those changes – although I am also sure they would argue that academics, trade unionists and others need to work together to help make sure those rights are enforced for the thousands of vulnerable workers in the current labour market. And we must always be vigilant and ask good questions that help us evaluate arguments and evidence when policy makers and others want to roll back those hard won gains.

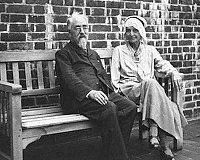

For more images of the Webbs and LSE, see our Pinterest boards.

——————————————————————————

Melanie Simms is Associate Professor of Industrial Relations at the University of Warwick. She writes and publishes on topics including trade unionism, youth (un)employment, and collective interests at work.