Eva Illouz’s new book on the sociology of contemporary relationships is not simply a feminist text that laments the plight of women. Jacqui Gabb finds that Illouz unpicks the artifice of evolutionary biology and psycho-dynamic accounts which seek to cleave open ‘natural’ differences between men and women. The author’s positioning of emotions as part of social structures is a timely provocation and makes a valuable contribution to the sociology of emotions, but there is weakness in her focus on heteronormative relationships.

Eva Illouz’s new book on the sociology of contemporary relationships is not simply a feminist text that laments the plight of women. Jacqui Gabb finds that Illouz unpicks the artifice of evolutionary biology and psycho-dynamic accounts which seek to cleave open ‘natural’ differences between men and women. The author’s positioning of emotions as part of social structures is a timely provocation and makes a valuable contribution to the sociology of emotions, but there is weakness in her focus on heteronormative relationships.

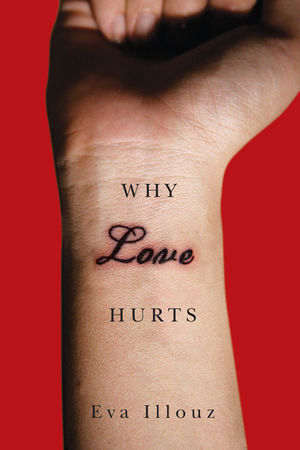

Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation. Eva Illouz. Polity Press. March 2012. 300 pages.

Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation. Eva Illouz. Polity Press. March 2012. 300 pages.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

![]()

In Why Love Hurts, Eva Illouz interrogates the travails of modern love and charts a course through the emotional geography of contemporary feeling. Her premise is that the quest for love is an “agonizingly difficult experience” resulting in collective misery and disappointment which is internalised by individuals (primarily women) as personal failing. The urgent sociological endeavour, she argues, is to relocate this individualised account away from deficient psyches towards the “set of social and cultural tensions and contradictions that have come to structure modern selves and identities” (p.4). Here Illouz adds a much needed intervention, shedding light on how the personal and the social intersect in shaping the romantic self in late modernity. She suggests that the individual navigates their way through complex social structures and institutions which frame the rules around and cultural rituals of love, drawing on the resources which they have personally accumulated. It is this social-psychic trajectory which Illouz posits as the modern condition of love; an experience that is shaped through inevitable suffering.

Pre-Modern relationship experience was tightly governed by a clear system of signs which codified and ritualised signs of feeling. Contemporary experience, she argues, is constituted through the de-regulation of marriage markets and freedoms around the choice of partner. The rules of emotional engagement may remain highly structured but the conditions within which choices are made have changed significantly. Moreover, the rationalism which characterises late modernity has led to uncertainty and irony. Rather than blind faith, love has become “the object of endless investigation, self-knowledge and self-scrutiny” (p.163). Both love and rationality have been rationalised. Today partner selection has become dis-embedded from publicly shared moral, social and economic factors. Love has become dis-embedded from social frameworks and as such has become the site through which the self is validated and valued. It has become a matter of the (subjective and individualised) heart, and for women, as the eponymous title tells us, love hurts.

This is not, however, simply a feminist text that laments the plight of women. Illouz unpicks the lure and artifice of evolutionary biology and psycho-dynamic accounts which seek to cleave open ‘natural’ differences between men and women. She points to the “concrete social relations” through which gendered partnerships are fashioned. These, she demonstrates, enable men to achieve fulfilment and a sense of self worth through their public status, such as a successful career. For women, however, love is not just a cultural ideal; it is “a social foundation for the self” (p.247). Egged on by the ever-present barrage of media advice on how to achieve relationship success, women are encouraged to engage in constant self-scrutiny, in search of ‘real love’, because, or so we are told, only through this can women find themselves. But, Illouz asserts, there is no resulting sense of fulfilment in such a quest. Instead this introspection creates ambivalence, a sense of dissatisfaction that we can never know or trust what our true feelings may be. Balancing the uneasy bedfellows of ambivalence, irony and the desire for love creates disappointment. It is, she contends, disappointment (and the corollary management and acceptance of disappointment) which is the overriding characteristic of love today.

There are many fine qualities to commend this book and it is highly readable; but there also some significant problems with the underlying argument and the way that it is advanced. Illouz weaves together a myriad of sources, from Regency literature, to the plethora of social networking sites on the Internet and handbooks which speak to and generate dialogue on the many contemporary forms and practices of relationships, to the original empirical research which she conducted on the topic. These sources provide fertile ground from which she draws together and develops historical, sociological, psychological and cultural studies perspectives to illustrate and advance her points. She even flirts with the bio-sciences. This interdisciplinarity serves to enliven and enrich the text but it does lend a sense of superficiality to her argument. The points that she makes are typically well rounded but the evidence is drawn from a net so widely cast that the claims being made are not always robust.

The eclecticism of the text can also make the intricacies of her argument at times hard to follow, as she slips seamlessly from one mode of thinking to another. For example, Raymond Williams’ ideas on ‘structures of feeling’ are introduced, before moving on to blog extracts from Catherine Townsend, which leads into the philosophical thinking of Schlegal and Kierkagaard and then on to the queer theorist David Halperin, before rounding off with Plato and a dash of literary criticism from Vivian Gorrick. All of this in fewer than two pages of text! (pp.195-197). It is not that different sources and perspectives cannot productively talk to one another and their fusion shed new light on phenomena; it is the pace at which such associations are forged which tends to undermine the approach. Collisions and conflations are inclined to obscure the complexity of ideas and any nuances and ambiguities which may arise. My point here does not seek to contest the merits of Illouz’s interdisciplinary endeavour. It does, however, suggest that some of the claims being made would benefit from being tempered and, the seamlessness of the joins unpicked to include the frayed edges of complex experience which characterises lived lives. Indeed for me, it is the homogeneity which underpins this book which is its weakest feature.

Illouz argues that it is through an analysis of love that we can better understand the conditions and transformations which constitute modernity. Paradoxically she then categorically asserts that the argument advanced in this book is not relevant to women who are situated or who situate themselves outside of the heteronormative conditions which structure social relations. Those excluded from her analysis include lesbians and women who resist the heteronormative ideal of wife and mother. These exclusions, she argues, are justified because heteronormative love fuses the emotional and the economic, and, through her analysis, their disentanglement reveals the wider conditions at play which shape modernity. This may be true. However, and importantly, by situating all of these ‘other’ women outside the remit of her argument she serves to privilege the heteronormative and coupledom as taken-for-granted with the result that modernity, thus packaged, remains untouched by the lives and loves of these others. It is not. A significant characteristic of late modernity is how it has incorporated and re-produced sexual diversity. There are other significant omissions which are equally troublesome. Class and racial diversities are effaced. So too the experience of couples who, despite their inequalities, may be happy in their relationship having reached some sense of equilibrium and/or contentment.

Notwithstanding the author’s prohibition, that as one of these ‘other’ women there is nothing in this book for me, I did, however, find much to commend it. Why Love Hurts offers many interesting ideas and these deserve to be taken up and systematically interrogated. Her positioning of emotions as part of social structures is a timely provocation and makes a valuable contribution to, and indeed revitalises and reorients the sociology of emotions. It will surely prove to make a valuable contribution as an addition to student reading lists, both for the ideas that it puts forward and for the lively debate and heart-felt discussion that it will generate among both women and men.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

5 Comments