The concept of virtue is central in both contemporary ethics and epistemology, yet in law there has only recently been an interest in virtue theory among legal scholars. Law, Virtue and Justice is a collection of essays examining the role of virtue in general jurisprudence as well as in specific areas of the law, with chapters on philosophical aspects and the relevance of empathy to our understanding of justice and legal morality. This collection moves current discussions forward and is sure to be a valuable resource for legal scholars and practitioners for years to come, writes Mark D. White.

Law, Virtue and Justice. Amalia Amaya and Ho Hock Lai (eds.). Hart Publishing. December 2012.

Law, Virtue and Justice. Amalia Amaya and Ho Hock Lai (eds.). Hart Publishing. December 2012.

Thanks to the 24-7 news cycle, we are more familiar than ever with the personalities involved in legal decision-making, such as judges, legislators, and lawyers. When academics and commentators debate the actions of legal actors, it is often in terms of consequentialist or deontological ethics, proclaiming that they should make a certain decision because it’s the best thing or the right thing to do. Ironically, given how closely we may feel we “know” these people, we rarely focus on the moral character of the legal actors as a factor in the decisions they make.

The seventeen chapters in Law, Virtue and Justice, edited by Amalia Amaya and Ho Hock Lai, do just that. Drawing from the “standard” Aristotelian account of virtue, as well as the views of Plato, Hume, Nietzsche, and Confucius, the contributors to Law, Virtue and Justice present a wide range of virtue-oriented perspectives on a variety of legal issues, especially jurisprudence and criminal law. The editors’ introduction provides a compact but reference-heavy summary of previous work on virtue and the law before summarizing the chapters in the book, which are organized in five sections. While all of the chapters contain much to commend them, I will focus on only two; as it happens, both are written by editors of the volume.

Of the several chapters in the book about judicial decision-making, Amalia Amaya’s chapter ‘The Role of Virtue in Legal Justification’ serves as the best entry point, building on Lawrence Solum’s seminal work in the area. (Solum also adds to his previous work in a chapter co-authored with Linghao Wang on Confucian jurisprudence.) Amaya goes beyond the claim that legal decision-makers should possess virtues like honesty and prudence in service of a consequentialist or deontological conception of law, as well as the claim that virtuousness of legal actors may support—but not constitute—the value of their decisions. She argues instead an essential role for virtue in which it serves as the basis on which legal decisions are assessed: a legal decision is right because it was made by a virtuous legal agent.

Amaya spends the balance of her concise chapter weighing strong and weak versions of her arguments, as well as confronting objections based on the priority of reasons (which she calls the publicity objection), the authority of the law, and disagreement about virtue themselves. These three distinct objections share a common element in that they all call into question the focus on the agent which is the hallmark of virtue ethics. They claim that too much emphasis is put on legal decision-makers rather than on the reasons on which they make decisions, the extent to which these reasons rely on legal materials, and the particular virtues that serve to justify their decisions. In response, Amaya deftly explains that the objections oversimplify the role of virtue in legal justification: for instance, virtue does not obscure the role of reasons based on the law, but rather governs how the legal agent develops and incorporates them. The chapter finishes with an abbreviated discussion on Aristotelian practical reasoning, which can be supplemented with the previous chapter by Claudio Michelson.

Amaya’s co-editor, Ho Hock Lai, contributes another standout chapter, ‘Virtuous Deliberation on the Criminal Verdict’. In this chapter, Lai considers the intellectual or epistemic virtues behind the well-known command given to juries to determine guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” However much this standard may be fleshed out, it can never made precise, leaving space that must be filled by judgment, “an inescapable dimension of verdict deliberation” (p. 243). This judgment is to be exercised with excellence as represented by virtues such as logical thinking, sensitivity to detail, and imagination (which aids in thinking of alternative explanations). Lai recognizes that virtuous deliberation may not lead to a factually correct verdict, just as correct verdicts may be the result of faulty deliberation, and so he examines the intrinsic virtues of deliberation separately from their instrumental value of finding the truth.

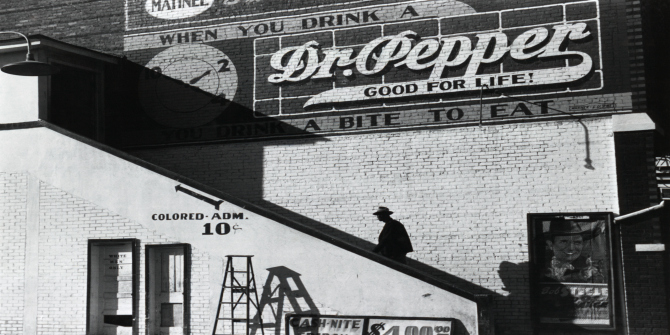

Confronted with a plethora of relevant virtues, Lai focuses on three, two of which are discussed in other chapters as well (contributing to the cohesiveness of the volume, a tribute to Ho and Amaya’s work as editors). An obvious epistemic virtue is practical wisdom, an essential element of all virtuous action and appropriately emphasized throughout the book (including Amaya’s and Michelson’s chapters, as mentioned previously). Another is empathy, which Lai frames as enhancing the concept of “justice as humanity,” and is revisited in the final section of the book by Michael Slote and others. Finally, Lai considers the vice of prejudice and the corresponding virtues: integrity, open-mindedness, and humility. This discussion is particularly timely given emerging knowledge as unconscious biases and the value of resisting them in full recognition of the difficulty of doing so.

If I have one small reservation about the book, it’s that several chapters, while valuable on their own merits, have a weaker link to law and justice than most. For example, Slote’s chapter on empathy summarizes his innovative work on care ethics but is light on legal implications; his commenters, John Deigh and Susan J. Brison, touch on the law slightly more as they critique Slote’s moral theory. Nonetheless, the focus of these three chapters (and Slote’s brief reply) seems to be on Slote’s conception of the ethics of care more than its connection to law—certainly an important discussion in its own right, but may disappoint readers who expected a steady focus on law through the lens of virtue ethics.

The virtue-oriented approach to law, in my opinion, offers the most direct and constructive response to legal formalism, the persistent belief that legal decision-making is simply a matter of mechanical deliberation based on legal evidence. It highlights the ubiquitous need for judgment while at the same time asserting standards of excellence for its practice (necessary to counter inevitable objections of “anything goes”). Amaya and Lai’s Law, Virtue and Justice moves this discussion forward in several different ways, and it is sure to be a valuable resource for legal scholars and practitioners for years to come.

——————————————————————–

Mark D. White is Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science, Economics, and Philosophy at the College of Staten Island/CUNY, where he teaches courses in economics, philosophy, and law. He is the author of Kantian Ethics and Economics: Autonomy, Dignity, and Character (Stanford University Press) and The Manipulation of Choice: Ethics and Libertarian Paternalism (Palgrave Macmillan), as well as dozens of journal articles and book chapters in the intersections between economics, philosophy, and law. He has also edited or co-edited a number of books on these subjects, including The Thief of Time: Philosophical Essays on Procrastination (with Chrisoula Andreou) and Retributivism: Essays on Theory and Policy (both from Oxford University Press). He can be found on Twitter and at his website. Read more reviews by Mark.

1 Comments