The cheap mobile phone is arguably the most significant personal communications device in history. In India, where caste hierarchy has reinforced power for generations, the disruptive potential of the mobile phone is even more striking than elsewhere. The book probes the whole universe of the mobile phone from the contests of great capitalists and governments to control radio frequency spectrum to the ways ordinary people build the troublesome, addictive device into their daily lives. Matt Birkinshaw hopes the broad scope and rich empirical detail found in this book will prompt a range of further, narrower, investigations in its wake.

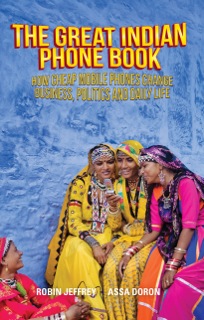

The Great Indian Phone Book: How The Cheap Cell Phone Changes Business, Politics, and Daily Life. Robin Jeffrey and Assa Doron. Hurst & Company, London. February 2013.

India had 4 million mobile phone connections in 2001; by 2013 there were said to be 990 million. In a country of 1.2 billion people this would make access to cell-phones far higher than access to sanitation. So how is the growth of this vast market transforming the world’s tenth-largest economy?

Jeffrey and Doron’s introduction to the rapid growth and social impacts of telecommunications in India combines a historian’s feel for the national narratives of politics, institutions and policies with an anthropologist’s eye for rich local context and individual stories. The authors offer a social history of mobile telephony for a popular audience that doubles as a broad snapshot of contemporary India. The prose is brisk and lively, packed with facts, interviews and ethnographic detail. Overall the book is informative, enjoyable, and very readable.

The original title—“Celling India”—is a stronger metaphor for the argument: the expansion of mobile phones as ‘selling’ the ideas and aspirations of ‘global capitalism’ to Indian retailers, workers and consumers, and training them in its practices (p.76-77). “Celling India” not only divides the country into ‘cells’ of signal coverage (p.xxxii) but also references the networking and “individualising” effects of mobile phones (p.216).

“Connecting,” the second part of the book focuses on the teachers and preachers of mobile telephony (missionaries) and the work and businesses that have grown up around production, maintenance and repair (mechanics). The major corporations invested in marketing to create demand and linked with local retail for distribution. The networks provided technical and customer service training to educate consumers and build trust. Sales became advocacy, for lifestyles and values as well as phones.

Cellphones are estimated to have generated four million jobs, and the strength of this section is the attention to this sector, particularly retail. Could phone sales and repair, as well as use, as the first step for many into India’s hi-tech boom? Here as in other areas, mobiles are a facet of wider trends. The shift in manufacturing from a predominantly male, unionised workforce to a new class of young, educated, female workers is not unique to phones. While, for consumers, mobiles involve a closer relationship with brands and suppliers than other utilities or technologies, in retail, many other outlets embody globalising India.

Jeffrey and Doron’s assessment of impact on cell-phones on business is more balanced. Except for cellphone support, the introduction of mobiles has not created additional livelihoods or impacted on equity, and support for claims that mobiles allow producers to bypass middle-men is ‘patchy and inconsistent’. Net benefits are low as buyers, suppliers and competition soon catch up with adaptations. New technologies may actually increase inequality by as more powerful groups are likely to adopt sooner and more thoroughly.

The most interesting story in this chapter again concerns the use of retail networks. EKO, a phone-banking start-up launched in 2007 wanted to make banking as simple as topping-up credit. 70% of India’s population lives in 600,000 villages while the country’s 75,000 bank branches are concentrated in larger towns. Persuading local shop-keepers to offer their service EKO had built up to 170,000 account holders across three states by 2011.

The section on politics illustrates the impact of the decentralised information “revolution” with a study of the Bahujan Samaj Party’s successful campaign strategy in the Uttar Pradesh elections of 2007. The success wasn’t attributable only to cell-phones, but wouldn’t have been possible without them. Mobiles allowed Dalit BSP activists to overcome cost, distance and status barriers to movement, bypass unsympathetic media, elaborate complex political messages, motivate supporters, and deter or document interference in voting. The ability of mobile connectivity to check abuses of power, such as vote-rigging and corruption, particularly through camera- and video-phones is a central element of the argument. However, by 2012 other parties caught up with the BSP, equipping their ‘workers’ with phones too, and BSP was not able to repeat their electoral success. While illustrating the progressive possibilities of mobile technologies, Jeffrey and Doron caution against technological utopianism, reminding us that politics is about social power. It seems hard to disagree with their suggestion that while technology boosts previously existing organisation and ideas it is unlikely to deliver social and political change by itself.

The argument is that users shape the social impact of technologies, within hard-wired constraints. The more interesting point that technology also shapes the way users function is, in this case, quite persuasive. Jeffrey and Doron argue that mobile phones deliver increased autonomy and a ‘networked individualism’ (p.215) that alters social structures, although not in a clear direction; as easily facilitating parental oversight or lovers’ trysts, communal violence or active citizenship. The stronger claim, though, that mobile phone subscriptions socialise people into the aspirations and practices of global consumer modernity (queuing, depersonalised interactions, contractual rights) and state ‘legibility’, I think has to be more provisional.

Jeffrey and Doron do stress a decline in the ‘grey market’ for mobile technology, and highlight potential spill-over effects, such as ideas of equality and motivations for literacy. In closing they offer the tentative hope that these changes will be “more democratic” (p.224). While mobiles may contribute to an ‘individual’ identity outside the family unit, there is no evidence that cell phones have weakened group identities of gender, class, language or caste. Optimism has to be found in piecemeal changes: increased social connectivity, innovative social applications such as mobile- and SMS-friendly e-governance, and the use of video-phones to capture police brutality.

Ultimately, this book won’t offer easy answers. Hopefully the broad scope and rich empirical detail on this new area will prompt a range of further, narrower, investigations in its wake. The book should be of interest to students of emerging markets, international development, sociology of technology, anthropology, South Asia, and bottom-of-pyramid models in business, marketing and social policy.

——————————————————————————————–

Matt Birkinshaw is PhD candidate in Human Geography & Urban Studies at the London School of Economics. Matt researches governance and infrastructure in Indian cities with a focus on urban water and municipal reforms. Read more reviews by Matt.

3 Comments