Despite living in the most secure of times, we see endangerment everywhere. Whether it is the threat of a terrorist attack, a natural disaster or unexpected catastrophe, anxieties define the global political age. While liberal governments and security agencies have responded by advocating a new catastrophic topography of interconnected planetary endangerment, our desire to securitise everything has rendered all things potentially terrifying. This is the fateful paradox of contemporary liberal rule, writes Brad Evans in his recent book. Liane Hartnett finds that the Orwellian tone may not appeal to all, but the importance of Evans’ project ought not be understated.

Liberal Terror. Brad Evans. Polity. February 2013.

Liberal Terror. Brad Evans. Polity. February 2013.

Brad Evans is a senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of Bristol, founder and director of the Histories of Violence project, co-director of Ten Years of Terror, and contributor to the Guardian newspaper’s Comment is Free. His book Liberal Terror is a timely invitation to those interested in international relations, critical security studies, and political theory to re-examine the phenomena of terror and its nexus with liberalism. A project of renewed relevance following the recent Boston bombings, Evans’ controversial assertion is this: Liberalism not only normalises terror, it creates and is sustained by it.

Evans understands ‘liberal terror’ as the:

‘global imaginary of threat which, casting aside once familiar referents that previously defined the organizations of societies, now forces us to confront each and every potential disaster threatening to engulf advanced liberal life’ (p.2).

As this quote may suggest, this book is a complex and challenging read. It is replete with references to ‘onto-theology’, ‘biophilosophy’, ‘imaginaries’ and ‘potentialities’. Citations of Foucault, Agamben, Baudrillard, Hardt and Negri, and Virilio abound. There is a risk this book will be consigned to a niche in continental philosophy or critical security studies. However, Liberal Terror is an important book for everyone interested in international relations. Its critique of liberalism’s collusion with terror and its invitation to reimagine ‘the political’ reopen a much-needed conversation more than a decade after 9/11.

Liberal societies, Evans argues, normalise terror. Abetted by security frameworks employed by organisations like RAND, we have come to embrace the narrative of a radically interconnected world where technology has largely diminished the significance of space and time. In this world, he suggests, all it takes is the actions of a few individuals to create catastrophe. ‘We have never been so dangerous’ Evans writes (p.86). Neither have we been so vulnerable. In our bid to preserve freedom as the zenith of liberal life, our focus shifts from what is to what may be. This fixation on ‘potentialities’ creates anxieties associated with possible threats that are largely ‘unknowable’, ‘non-identifiable’ and ‘unstoppable’. As ‘prevention’ morphs into ‘pre-emption’,

‘…[O]ur desire to securitize everything [renders] all things potentially terrifying… The more we seek to secure, the more our imaginaries of threat proliferate’ (p.88).

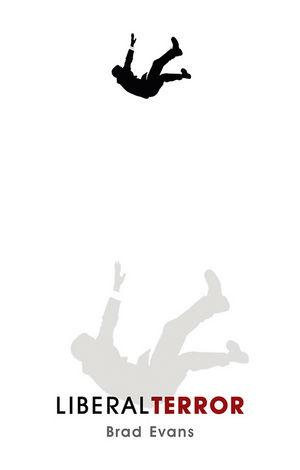

Desperately seeking security, the fraught pursuit of perpetual peace must entail a climate of perpetual fear. For Evans, this is less an accident of history than the product of liberalism. He charges Kant as chief culprit for promoting this poisoned ‘onto-theology’ or theology of being. The motif of the ‘fallen man’ – the deeply confronting image on the cover of the book – is central to this thesis. Kant’s secular reworking of the Biblical mythology of ‘the Fall’, Evans suggests, has profound consequences for liberal understandings of evil and eschatology. ‘Original sin’ cast as human imperfection makes evil a latent human propensity. Without the theological promise of final resolution or end-time, humanity is thrust into infinite possibilities of progress and regress. In this space between the noumenal and phenomenal, human finitude and the infinitely possible, the subject is bound ‘to the world in such a way that the governance of life assumes a moral imperative’ (p.111).

This Foucauldian-inspired critique of liberal terror concludes that global security is becoming a liberal regime of ‘bio-power’. In other words, global security legitimises liberalism’s governance of life. Rhetoric of our interconnectedness forces us to see the world in binaries, dividing the world into those ‘for us’ and ‘against us’. Not only does this stifle diversity, but it also enables dehumanisation evident for example at Guantanamo Bay. As human subjectivity is quashed, resilient life becomes focussed on survival rather than an engagement with the political. For Evans, this is necessarily born from the elevation of the economic and relegation of the political in late liberalism. The victims are justice and ironically, liberty. The victor, he seems to suggest, is liberalism.

Despite its many strengths, some might find aspects of this book problematic. Its Orwellian tone designed perhaps to mirror the hysteria of ‘liberal terror’ may not appeal to all. This 200 page tale about the involvement of liberalism for at least 400 years – in its philosophical, economic, environmental and imperial dimensions – in the erasure of human subjectivity seems at times ambitious and ironic. Similarly some might suggest its claim about the dangers and narcissism of liberalism is illuminating, but at least as old as liberalism itself.

Evans’ critique of liberalism raises many questions for liberals, Kantian scholars, and historians of political thought to further explore. If the legacy of liberalism spans at least from Hobbes to Hayek, do you lose nuance by suggesting that the entire tradition shares a commitment to the same ‘onto-theology’? Even if it did, could hope and fear exist in the same space between human finitude and infinite possibility? If liberalism is animated by a dialectic between hope and fear, does not the triumph of fear present a liberalism that has self-destructed? Does liberalism’s commitment to the economic, necessarily preclude a political philosophy premised on the promotion of inalienable values? Indeed, when does liberalism stop being liberalism and become the totalitarianism it supposedly seeks to resist?

Despite some of my doubts, the importance of Evans’ project ought not be understated. It calls us to find new ways of thinking about violence that affirm human subjectivity, to re-engage with the political free of the blinders of ideology. In this sense, it challenges the normalisation of liberalism as much as it challenges the normalisation of terror. And if nothing else, it seeks to save liberalism from itself.

—————————————————

Liane Hartnett graduated with a Master of Philosophy in International Relations, with Distinction, from the University of Cambridge. Previously, she worked in legal, policy and research roles in the Victorian government, Australia. Liane is admitted to practice as a solicitor and barrister of the Supreme Court of Victoria. She has a Bachelor of Laws and a Bachelor of International Relations, with first class Honours from La Trobe University, Australia and hopes to commence a PhD in international political thought later this year. She tweets @L_Hartnett. Read more reviews by Liane.