This book presents a moving and insightful portrait of Guyanese scholar and revolutionary Walter Rodney through the words of academics, writers, artists, and political activists who knew him or felt his influence. These informal recollections and reflections aim to demonstrate the importance of Rodney’s work on oppression and exploitation. Given renewed discords about race in the United States, these essays appropriately return us to the many focal debates during a time when restless ideas about civil rights, socialism, and African independence provoked the imagination, writes Jia Hui Lee.

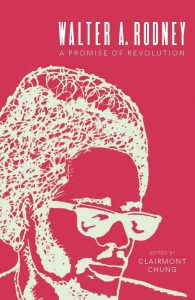

Walter A. Rodney: A Promise of Revolution. Clairmont Chung. Monthly Review Press. November 2012.

The personal recollections in Clairmont Chung’s edited anthology present an intimate and insightful look into the life of the late Walter A. Rodney (1942-1980), famously known for his work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Reflecting on this revolutionary scholar of Guyanese and African history, the essays reignite difficult discussions around inequality, race and violence, continuing Rodney’s commitment to “[change] the world” through his scholarship (p. 124). Political activists, academics, and artists whose writings are featured in this anthology are based in Guyana, Tanzania, New York, and Canada; places where Rodney has spent time developing his work. They offer portraits of a complex figure who was constantly trying to articulate why and how to effect change in the world.

Robert “Bobby” Moore’s essay recalls his encounters with Rodney during the latter’s student days in a prestigious high school in Guyana. Moore tells us about Rodney’s “gift for leadership” (p. 30), his wit, and a natural inclination for debating. After high school, Rodney completed his undergraduate degree in History on a scholarship at the University College of the West Indies; he then won another scholarship for his Ph.D. in African History at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, where he produced academic work that would go on to receive many accolades.

Abyssinian Carto recounts the moments before and after the car explosion in June 1980 that killed Rodney. Those few weeks were intense for Rodney and other members of the Working People’s Alliance (WPA), as they were under constant police surveillance. Rodney and other WPA members struggled to ensure that the party’s membership was multiracial in the face of an increasingly dictatorial president, whose political party forged a new form of ethnic politics that divided the blacks from the Indians. Carto’s description of having to endure police brutality and the fear of being assassinated by the regime gives a glimpse into the precariousness with which Rodney must have lived his final days.

Rodney’s life may have been bookended by time spent in his home country Guyana. But his life and work brought him across the globe and to Tanzania, where he was further politicised by the Tanzanian president’s socialist development plan, or Ujamaa. As Amiri Baraka tells us, one of the important things that Rodney always said was that “We cannot let racism and white supremacy deprive us of the most important things white people have said” (p. 71). Rodney was referencing Marxism. From Baraka’s and other essays, we begin to realise that Rodney’s stint in Tanzania coincided with a time of political experimentation and hope; it was these ideas of socialism and self-sufficiency, coupled with Africa’s colonial experiences, that influenced his most famous work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

Despite Rodney’s restless crisscrossing of the continents, he decided to return to Guyana in order “to go back to the people [he knows] and who [knows him]” (p. 89). His participation in political debates and conversations unsettled the Tanzanian government, resulting in an order for him to leave the country. Issa G. Shivji’s essay explores some of the tensions that emerged between Rodney and other fellow Tanzanian activists and the government, revealing how Rodney might have negotiated his identity as a non-Tanzanian activist. Shivji however thinks that Rodney wanted to return to Guyana because he felt that he could make a contribution.

Everywhere Rodney went he seemed to leave a considerable impact and unsettle those in power. He was deported from Jamaica, where he was teaching, and was ordered to leave Tanzania, where he was also teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam. But his ideas and scholarship on the history of Africa have sparked an ongoing debate about colonialism, agency, and development that continue to frame the study of Africa today. These questions thread through the essays in Chung’s anthology, too.

But rather than try and answer the questions posed by Rodney’s work, the anthology offers a glimpse into his life, through the impressions of people who have met, worked with, and sometimes disagreed with Rodney. In Shivji’s essay, he writes that “Walter was an institution” (p. 90), a remark that fittingly captures the impact that Rodney has had on an entire generation of scholars and political activists. What this anthology adds to our understanding of Rodney’s work is to provide the circumstantial context to help us peel back the layers on this “institution” and meet Rodney through the eyes of some of his contemporaries.

The essays, along with their individual cadences and manners of speech (as they were originally recorded as interviews for Chung’s 2010 documentary film W.A.R Stories: Walter Anthony Rodney), distils a certain spirit from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. Given renewed discords about race in the United States and an emerging corporate-Africa, these essays appropriately return us to the many focal debates – and how Rodney might have encountered them – during a time when restless ideas about civil rights, socialism, and African independence provoked the imagination.

———————————————

Jia Hui Lee is a postgraduate student in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. His research has focused on the relationships between neoliberal capital and sexuality, changing conceptions of gender across time and place, and international development. He is also working on developing community organising approaches through his work in the students’ union and in ethical investments. Read more reviews by Jia Hui.

Find this book:

Find this book: