Is it sensible for human rights to make use of measurement tools such as indicators? Is the ‘cost’ of human rights an argument that can and should be used by proponents of human rights? In this book Thérèse Murphy aims to chart the history of the linkage between health and human rights. Kate Donald finds that this is an enlightening read that suggests some interesting avenues for human rights practice. Recommended for human rights activists and researchers.

Health and Human Rights. Thérèse Murphy. Hart Publishing. August 2013.

Thérèse Murphy’s contribution to Hart’s Human Rights Law in Perspective series examines the different – and often fascinating – ways that health and human rights have intersected in law, advocacy, and practice. Engaging and very readable, it is a thought-provoking collection for human rights advocates and health activists, although it is unlikely to be a useful resource for newcomers to human rights law. Despite some strange omissions (the universal health care movement is barely mentioned), Murphy certainly succeeds in illuminating some fascinating conundrums within health and human rights, discussing for example how patient autonomy and patient choice – a seemingly unequivocal good – has led to troubling outcomes such as direct-to-consumer marketing by pharmaceuticals.

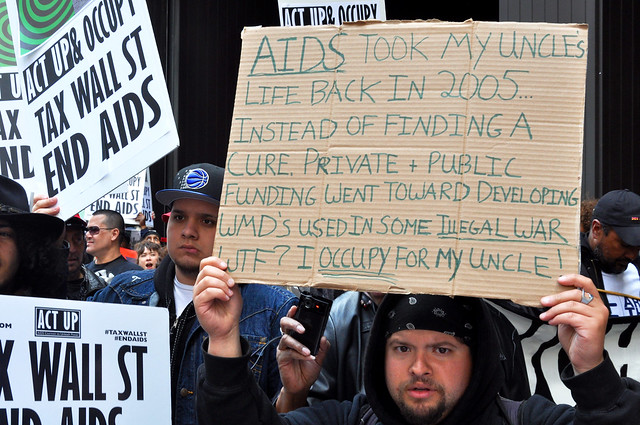

After an introduction and a chapter focused on the history of health and human rights, Murphy presents four chapters exploring different trends, methods and case studies that illustrate potential avenues and challenges for the field. Most enlightening are the middle two chapters, the first of which focuses on the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) in South Africa. TAC was at the vanguard of the health and human rights movement and widely known for securing (at least in theory) access to anti-retrovirals for poor South Africans, first against the callow profiteering of the pharmaceuticals and then against the AIDS-denying South African state. Murphy’s analysis skilfully explores the wider impacts of the TAC’s triumph on the broader health environment in South Africa and on health rights work globally, including for example the accusations that it skewed attention and resources away from other devastating diseases.

The TAC’s strategy serves as a crucial example in two respects. First, they explicitly engaged with something that advocates often wilfully neglect: the actual financial expense entailed in meeting human rights obligations. Realizing rights does entail a cost; to obscure or deny this is dishonest and ultimately unproductive. Thankfully, human rights scholars and advocates are beginning to engage more with budgets, public finances and fiscal policy, wielding these analyses as weapons against the ‘unaffordability’ claims so often presented by States as supposed trump cards. The TAC provides an inspiring model for how human rights actors can win the argument by getting ahead of the cost issue rather than hiding from it – not only securing cheap and free drugs but also proving that widespread provision of ARVs was, in fact, affordable.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in fact provides an explicit tool for this work in its concept of ‘maximum available resources’ – somewhat mischaracterized by Murphy as “a concept to limit state obligations in the field of ESC rights”. I would argue that it is quite the reverse, an obligation for States to mobilise their resources in ways that prioritise rights fulfilment. Budgets that invest more in military spending than health; tax structures that grant huge tax-breaks to corporations while raising VAT on basic goods; regimes that leak billions of dollars that could be spent on poverty reduction through corruption and illicit financial flows: none of these can be said to be rights-compliant.

Secondly, as Murphy shows, the TAC’s success was in large part down to its dual nature, as both a litigant and a social movement. The TAC wielded the law strategically, but it also used campaigning tools and built pressure from the bottom up. Although Murphy somewhat overstates the extent to which this was a new or exceptional model, she is surely right to urge that advocates think more carefully “about the place of litigation in achieving justice” and engage more honestly and strategically with politics as part of a broader rights-based strategy.

Murphy’s next chapter focuses on what is arguably an existential challenge for the modern human rights field – the increasing turn to indicators and quantitative measurement. She ably explores the potential effects and ethical considerations of this, particularly the risk that organisations will be driven to work on what can be measured (and celebrated with “champagne moments” when targets are reached) rather than what matters most. However, Murphy does not give enough acknowledgement to the role of donors in pushing this agenda, central to understanding the very ambivalent response by human rights actors. In some senses, health initiatives may benefit from the turn towards indicators at the expense of other social justice or human rights work, because they have aspects that are comparatively easy to measure – patients treated, clinics built, vaccinations given. However, there is a clear danger that the measurement drive will lead us to focus on the ‘easy’ wins, rather than addressing the structures that create poverty, inequality and their attendant bad health outcomes, or hard-to-measure issues like body sovereignty or health empowerment. Murphy is asking important questions here: “what should be counted, what can be counted and what effects it has to count one thing and not another”.

Indeed, the book is characterized by incisive questions; but it would be more satisfying if these were accompanied by more serious consideration of potential strategies and ways forward. The exposition also occasionally veers off course from illuminating and idiosyncratic into unfocused and obfuscating. For example, Murphy’s theory of ‘risk within rights’ and ‘rights as risk’ is somewhat incoherent, and does not add much to existing interpretations of the scope and limitations of rights. However, overall Murphy certainly succeeds in making us think more deeply and critically about health and human rights, and the benefits, tensions and dangers in tackling the former through the lens and practice of the latter.

The book is certainly timely. Although health rights have achieved considerable support and status in a short period, we are now seeing threats to progress on many fronts: austerity measures are slashing funding to health budgets, the HIV/AIDS pandemic continues on a devastating scale, the polio eradication campaign – tantalizingly close to succeeding – has suffered significant setbacks. As the author says, “Human rights law is a way of protecting what we do and should care about; it allows and obliges us to reason in particular ways about what matters.” Murphy’s own thoughtful reasoning about these questions is ultimately enlightening, suggesting some interesting avenues for human rights practice.

————————————-

Kate Donald works as Adviser to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. Since graduating from the LSE with a Masters in Human Rights in 2009, she has worked at the International Council on Human Rights Policy and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva. Read more reviews by Kate.

Find this book:

Find this book:

2 Comments